Looking back I can see that a project like this begins with an idea which expands into a vision – an idea that inspires and a rough idea of how it might work. It continues with presenting the idea to others and persuading others to be involved (since this is intended as a social learning process) and it continues with designing the process in detail and developing the tools (eg guidance and exemplars) and the technological infrastructure to support the social learning process. Then you have to find and persuade people who have not been part of the design process to participate. And once the process has started you have to facilitate – encourage, provoke, support, guide – do whatever is necessary to try to make it work. Then, stuff emerges from the process, you have to help synthesise and curate it, for only then will you know what you have explored. And all this has to be done within the time frames you have set for the project. The net effect is to provide many affordances or opportunities for learning. Every stage of the process, every communication and other form of interaction and every artefact that is produced contains within it the potential to use existing learning and to extend or adapt that learning in the current situation and circumstances. The whole process and practice might be conceived as ‘learning to do it all over again for the particular situation and set of circumstances.’ Although we might pull out examples of new leaning in any part of this process, for me the most important learning is the metalearning, ‘the execution of the whole and what emerged from the whole.’ In an ecological sense this is the way that everything has been woven together to achieve the result. It’s the metalearning that provides the platform for the overall advancement of understanding and achievement.

|

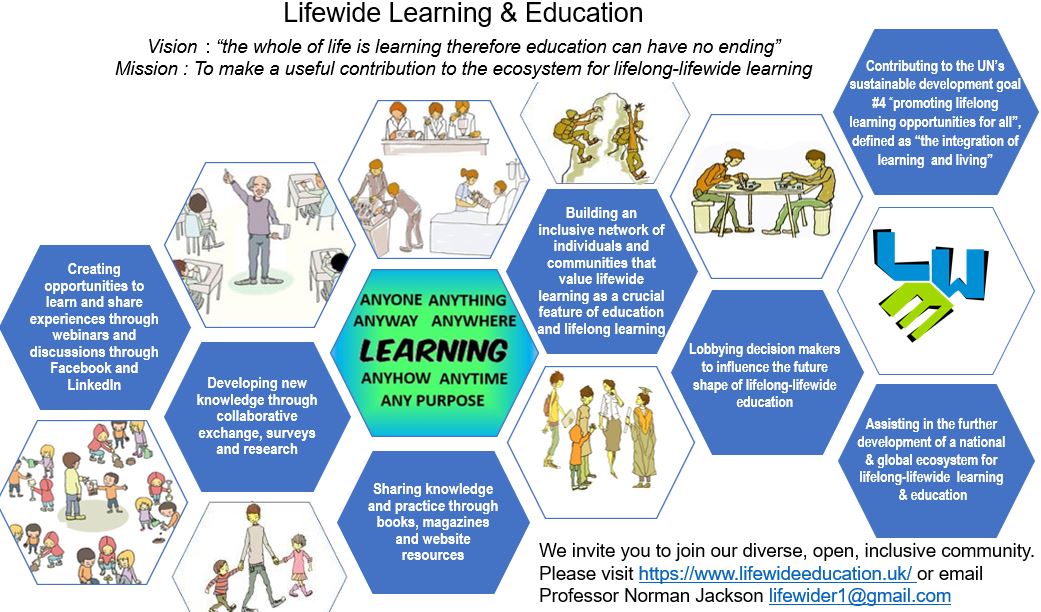

It's hard to believe but this year is the 10th anniversary of Lifewide Education. Over the last six months we have been expanding our small core team of supporters and prepared a vision statement for the next decade. Last week we agreed our work plan for the year and our first activity is to try and engage in a research project that aims to develop a better shared understanding of what lifewide learning means in our own lives. For the past few weeks I have been working with my co-facilitator Rob Ward to prepare for the 6 week project which begins on Feb 1st. This is my story so far.

Looking back I can see that a project like this begins with an idea which expands into a vision – an idea that inspires and a rough idea of how it might work. It continues with presenting the idea to others and persuading others to be involved (since this is intended as a social learning process) and it continues with designing the process in detail and developing the tools (eg guidance and exemplars) and the technological infrastructure to support the social learning process. Then you have to find and persuade people who have not been part of the design process to participate. And once the process has started you have to facilitate – encourage, provoke, support, guide – do whatever is necessary to try to make it work. Then, stuff emerges from the process, you have to help synthesise and curate it, for only then will you know what you have explored. And all this has to be done within the time frames you have set for the project. The net effect is to provide many affordances or opportunities for learning. Every stage of the process, every communication and other form of interaction and every artefact that is produced contains within it the potential to use existing learning and to extend or adapt that learning in the current situation and circumstances. The whole process and practice might be conceived as ‘learning to do it all over again for the particular situation and set of circumstances.’ Although we might pull out examples of new leaning in any part of this process, for me the most important learning is the metalearning, ‘the execution of the whole and what emerged from the whole.’ In an ecological sense this is the way that everything has been woven together to achieve the result. It’s the metalearning that provides the platform for the overall advancement of understanding and achievement.

1 Comment

I recently participated in a WISE on-line seminar on learning ecosystems and was impressed with the contributions by David Atchoarena Director UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL), so I emailed him after the event. He responded and I had an hour long discussion with Deputy Director and Head of Policy Dr Raul Valdes Cotera. I felt energised that this international agency was interested in our ideas on lifewide learning and learning ecologies and in the past week I have made a substantial effort to try to find out more about the work of the UIL and its Future's of Education Initiative. I began an essay to try and map the strategic thinking of UIL to see how we might relate the work of Lifewide Education. Over Christmas the essay morphed into what I'm calling a White Paper whose purpose is to make explicit how these ideas might be used to enrich the concept of lifelong learning which is one of the goals of the UIL Futures of Education Initiative. It involved a fair amount of work but I became convinced that it was worth the effort and I was pleased because it enabled me to see how our ideas could be used to help people learn their way into the future. I emailed the paper to Raul on January 1st and I'm hopeful that he will be receptive.  Postscript 19/01/20

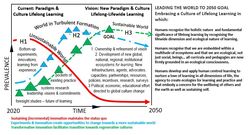

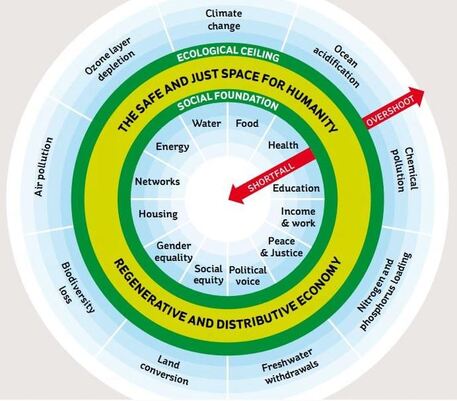

I received an email from Raul on Jan 11th inviting me to contribute a post to the UIL blog and to contribute to their series of webinars and also their institutional case studies so I interpret this to mean that the ideas I was offering were of interest and worthy of wider exposure. I have just submitted my blog post and look forwards to seeing how this story unfolds. Enriching the Concept of Lifelong Leaning by Embracing the Lifewide Dimension of Living Norman Jackson Mankind has always engaged in lifelong learning but it has meant different things at different points in our history and this will always be the case. The contemporary world obliges people to learn and to keep on learning throughout their lives for a world in rapid formation. It’s a complex, hyperconnected, turbulent, sometimes confusing and increasingly disruptive world. It’s also a fragile world that cannot be sustained if we carry on using it in the way we have. The idea that lifelong learning can be harnessed in the service of sustaining our presence in this fragile world is emerging in the thinking of the world’s global strategic planner. The wicked problem of our survival is framed by the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which offers 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Education has its own SDG 'Ensure inclusive and equitable quality and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all'. This SDG gives education a new role – to educate the world in ways that will encourage behaviours that will support sustainable development. The UNESCO Futures of Education initiative aims to rethink education, knowledge production and learning from a future-oriented perspective. The first report of this initiative (1) presents a future-focused vision that demands a major shift towards a culture of lifelong learning by 2050. It argues that the unprecedented challenges humanity faces, require societies to embrace and support learning throughout life and people who identify themselves as learners throughout their lives. For this ambition to be realised there would need to be significant changes in culture and practice at a global scale. It requires a culture that transcends all other cultures, that values learning in every aspect of life. It’s a vision of a culture that reaches beyond the idea of “promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all” to the belief that “the whole of life is learning therefore education can have no ending” (2). Perhaps the time has come to develop and enrich the concept of lifelong learning in the service of humanity and the planet, by embracing consciously and fully the lifewide dimensions of everyday life. I believe that the act of making the lifewide dimension of learning explicit would make a significant contribution to the goal of ‘a more holistic understanding of lifelong learning’ because lifewide learning gives day to day practical expression and meaning to lifelong learning. For lifelong learning is the accumulation of all our lifewide experiences and what we have learnt and become through them. Lifewide learning (3) adds the detail and purpose to the lifelong pattern of human development by recognising that most people, no matter what their age or circumstances, simultaneously inhabit a number of different spaces - like work or education, being a member of a family and a community, managing a home, caring for others, engaging in sport and other interests, and looking after their own physical, mental and spiritual wellbeing. So the timeframes of lifelong learning and the multiple spaces and places for lifewide learning will characteristically intermingle and who we are and who we are becoming are the consequences of this intermingling. It is in the lifewide dimension of our life that we learn what it is to be human in the contexts of our own lives by discovering our purposes and what we value and care about. It is in this dimension of our life that we also learn about the world in all its diversity and confusing complexity, through the media we access, or the experiences of others we know, or through our own experience as we travel to cultures that are different to our own. If we are to create a culture that is committed to sustaining the world, it is the lifewide dimension of learning we have to nurture. Through an education for sustainable development we can develop the knowledge to enable us to sustain our future. But we have to apply this knowledge in every part of our life and keep on learning how to do it for the rest of our lives, and that requires both agency and will. It is precisely because every individual’s lifewide learning is a product of their historical and current interactions with their unique environments and circumstances, that they are the unique person they are. This is what makes us different from machines -everyone one of us is one of a kind and that is to be celebrated. It is also the real meaning of personalised learning and it provides a better foundation for understanding the scope and nature of lifelong learning as it is embodied, enacted and experienced by every person on planet. I welcome your views on these ideas and the White Paper on which it is based, which can be found at: https://www.lifewideeducation.uk/white-paper.html Sources 1 UNESCO (2020b) Embracing a culture of lifelong learning: Contribution to the Futures of Education Initiative Report : A transdisciplinary expert consultation UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Paris Available at: https://www.sdg4education2030.org/embracing-culture-lifelong-learning-uil-september-2020 2 Lindeman C (1926) The Meaning of Adult Education New York: New Republic. Republished in a new edition in 1989 by The Oklahoma Research Centre for Continuing Professional and Higher Education. Available at: https://openlibrary.org/books/OL14361073M/The_meaning_of_adult_education 3 Jackson, N. J. (ed) (2011) Learning for a Complex World: A Lifewide Concept of Learning, Development and Achievement Authorhouse Available at: https://www.lifewideeducation.uk/learning-for-a-complex-world.html 4 UNESCO (2020a) Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. Paris Available at: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development  Humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend – such as a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer. The idea and model of Doughnut Economics promoted and popularised by Kate Raworth is a scientifically-founded metaphor to help us think about how we can live sustainably on the planet (see figure).The environmental or ecological ceiling consists of nine planetary boundaries, as set out by Rockstrom et al, beyond which lie unacceptable environmental degradation and potential tipping points in Earth systems - the systems all life depends on. The twelve dimensions of the social foundation are derived from internationally agreed minimum social standards, as identified by the world’s governments in the UN's Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. Between social and planetary boundaries lies an environmentally safe and socially just space in which humanity can thrive. Doughnut Economics Synthesis The inner ring of the doughnut represents the basic needs of flourishing human society - which we often fall short of. The outer ring represents the limits of planetary resource use - which we often overshoot. The gap in-between the rings is the zone where we should be aiming for - what Raworth calls "the safe and just space for humanity", powered by a "regenerative and distributive economy". In all Raworth's graphs this looks as if it may be a decently-sized zone to occupy. The trick of it is understanding that to meet all the factors of "social foundation" does not mean intensifying consumer society to the max. Beyond a certain level of income and consumption, our sense of satisfaction flatlines out, no matter how much more we earn and buy. If we grasp that, and answer our social needs in a non-conventional way, we can easily live "inside the ring of the doughnut". The inner ring of the doughnut represents the basic needs of flourishing human society - which we often fall short of. The outer ring represents the limits of planetary resource use - which we often overshoot. The gap in-between the rings is the zone where we should be aiming for - what Raworth calls "the safe and just space for humanity", powered by a "regenerative and distributive economy". In all Raworth's graphs this looks as if it may be a decently-sized zone to occupy. The trick of it is understanding that to meet all the factors of "social foundation" does not mean intensifying consumer society to the max. Beyond a certain level of income and consumption, our sense of satisfaction flatlines out, no matter how much more we earn and buy. If we grasp that, and answer our social needs in a non-conventional way, we can easily live "inside the ring of the doughnut". Raworth presents us with an inspiring target. But a study from the authoritative science magazine Nature (which is based on an impressive project from Leeds University) indicates just how far away from managing to live within the doughnut the vast majority of countries currently are. (Assuming, that is, their present ways of using resources don't improve). I really like this powerful advocacy for changing our view of growth economics. "If we are going to do this we need to change the conversations in our parliaments about what the economy is and what its for and how it works and what success is." Sources Rockström, J., W. Steffen, K. Noone, Å. Persson, F. S. Chapin, III, E. Lambin, T. M. Lenton, M. Scheffer, C. Folke, H. Schellnhuber, B. Nykvist, C. A. De Wit, T. Hughes, S. van der Leeuw, H. Rodhe, S. Sörlin, P. K. Snyder, R. Costanza, U. Svedin, M. Falkenmark, L. Karlberg, R. W. Corell, V. J. Fabry, J. Hansen, B. Walker, D. Liverman, K. Richardson, P. Crutzen, and J. Foley. 2009. Planetary boundaries:exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society 14(2): 32. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/ The Alternative UK https://www.thealternative.org.uk/dailyalternative/2018/3/7/living-in-the-doughnut-slm59 I reconise that whenever I encounter a new thought/idea it triggers a process in which that idea keeps emerging and connecting with other thoughts and opening new possibilities. New ideas encounter a context and the right context will provide an environment in which I devote time and energy. So the context is trying to breathe more energy and purpose into Lifewide Education. In the last few months, with the help of our small supporters group we have undertaken a review of what we have achieved in the last 10 years and then tried to imagine how we might sustain our enterprise into the future. Like any organisation we have tried to create a vision of our future that we share and we have codified this vision in a 2 page statement that we can share.

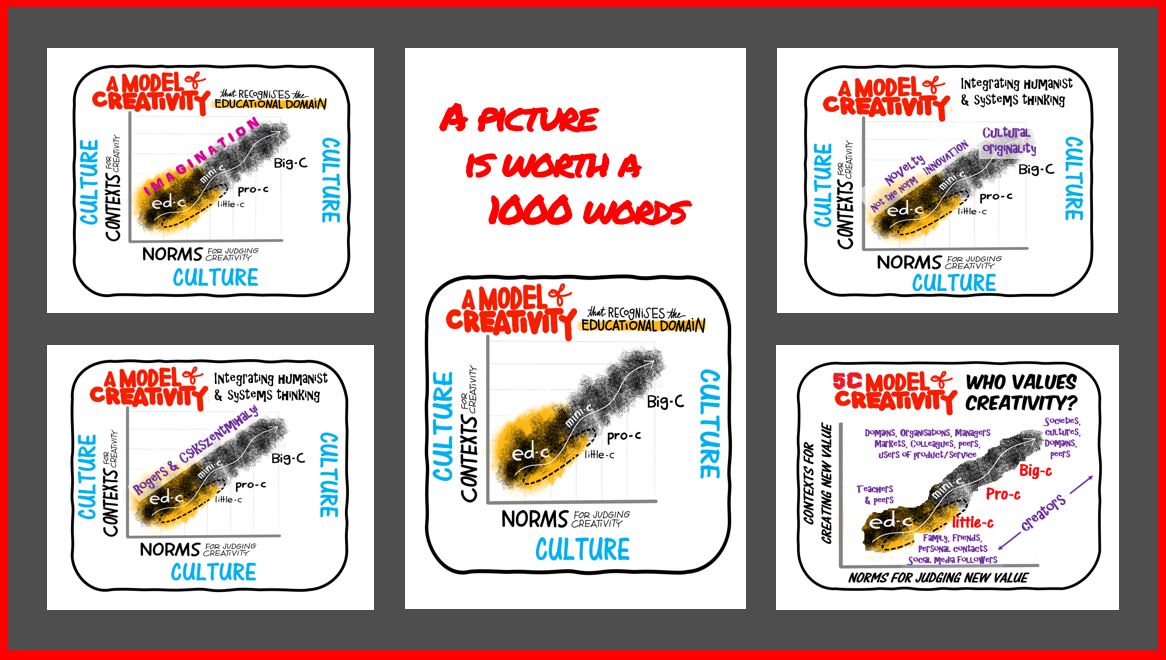

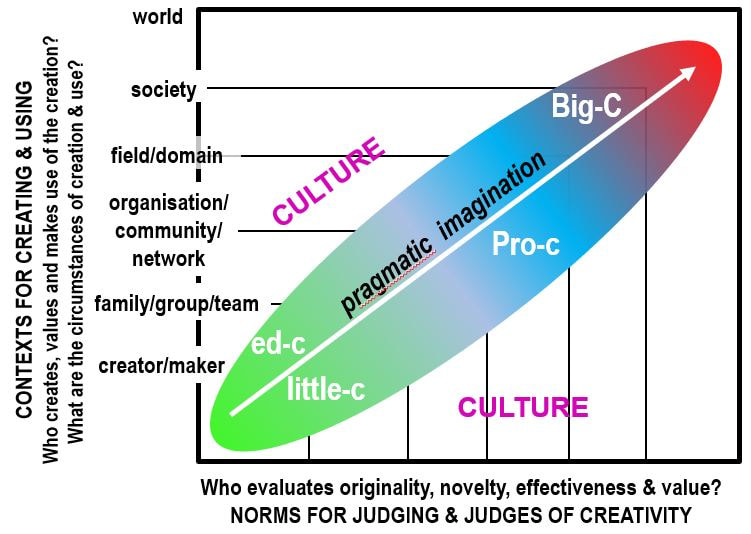

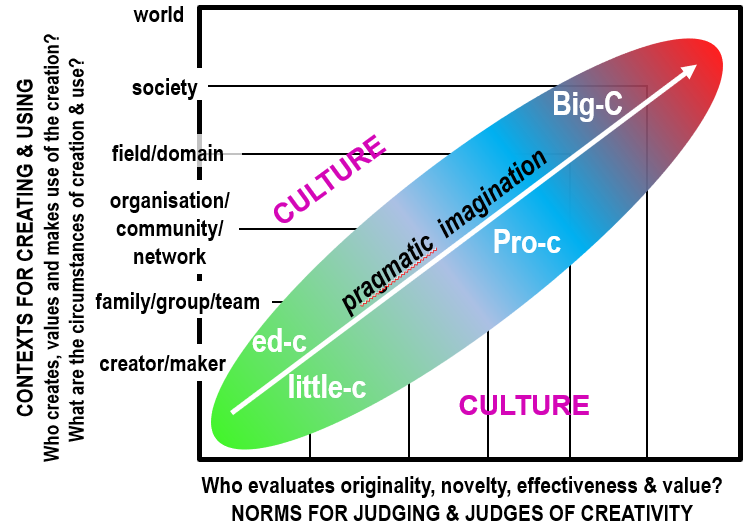

The changes we are planning in our own activities are quite small – pragmatically they reflect the resources we have and our capacity to affect the world as it exists now. But we also realise that what we do now affects the future and so we are positioning our agency and the products of our work within an expanded vision of the way the world is evolving. We are seeing our modest efforts in the contexts of the powerful forces that are affecting the very sustainability of humanity, the ecosystems that enable all life on the earth. We are aligning our own moral purpose to encourage holistic concepts of learning and the fundamentally ecological nature of learning, to the need for humanity to learn how to learn and behave in a way that sustains the world that has yet to come into existence. In order to do this we need to connect to and combine our modest efforts with more powerful national and international organisations. They say a picture is worth a thousand words because of its power to convey complex relational and conceptual information that is easier and quicker to comprehend than by reading the written words. Sometimes there is also a poetry in a picture that connects us emotionally with the subject. I started my professional life as a geologist – a subject in which diagrams are often used to capture the dynamics of processes. I carried on making good use of diagrams when I became interested in educational theory. I recently came across an invitation from Beau Lotto / labofmisfits to provide examples of artistic activities that changed perceptions. The first thing that came into my mind were the diagrams I create to convey complex meanings. This year I have been developing a visual aid or tool to explore different aspects of creativity. The well known and much referenced 4C model of creativity developed by James Kaufman and Ron Beghetto1 is provided as a textual description. Turning their words into a conceptual picture creates a visual aid that is much easier to understand. The diagram or map can be used to explore (play with) ideas, different questions and perspectives in a far more efficient and effective way than by words alone. A diagram like this is also a tool to encourage playful and exploratory thinking: it provides a framework within which ideas can be located, connected, related and communicated. Last October while participating in an inquiry into learning ecologies in Harvard Universities Learning Innovations Laboratory I met a graphic facilitator called Sita Magnuson. I was impressed with the way she turned my talk into a narrative picture on the wall. I kept in touch and since then she has drawn a number of illustrations for me. I am quite capable of drawing a diagram in word or power point but the hand drawn illustrations she creates are far more interesting and poetic. She kindly produced the centre image in the panel and I was then able to derive a family of conceptual images using a combination of paint, snipping tool, powerpoint and lunapic software which I have used in my talks, articles and social media posts.

In the last week we have had some stunning sunsets. So beautiful that I would not know how to begin to describe them and how they fill me with wonder. Its a wonderful illustration of why a pitcture is worth a thousand words.  Reaching 70 only happens once in our life - if we are fortunate to reach this age - so it is worth celebrating. I woke up to an amazing fresh and sunny day with the dew heavy on the grass. It reminded me so much of the early September saturday mornings I would play football when I was at school. I have so much to be thankful for the lucky coincidence that gave me life. I made a tower of 7 granite stones that I had collected 25 years ago from a river on Dartmoor to commemorate this moment and felt honoured that my brother in law dedicated his porridge to me.

News has just been released of the death of Sir Ken Robinson, who for more than twenty years had been the articulate and often humorous voice for why education systems need to profoundly change in order to nurture the creative talent that humanity surely needs.

The passing of a great man or woman is always cause for reflection. I never met Ken, but such was his affable personality and presence on the internet, I almost felt I knew him. I have watched many of his recorded presentations to live audiences and he had a wonderful gift of making you feel he was talking to you, often posing questions after he had shared a thought to check that you felt that way to. There is a reason that his talks are watched by millions and its because what he says resonates with what we also believe. Through his humorous personal anecdotes and carefully crafted stories he caught our attention and imagination and conveyed his wisdom. This style of communication was as effective in his books as it was in his much loved TED talks. He was a performer, entertainer and persuasive public speaker and did, perhaps more than anyone else, explain why education needs to make the development of learners’ creativity a priority if we are to cope with the unimaginably complex, uncertain and turbulent world we will have created in decades to come.

I first time I came across his ideas and work when I started working on creativity in 2001 for the Learning and Teaching Support Network (LTSN). In 1998, following the election of the Blair Government, because of his long and well known commitment to creativity in education, Ken had been invited to Chair a National Committee of Inquiry on Creative and Cultural Education. When I read his report, “All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education”. I was bowled over by the common sense and vision contained in the report and how the arguments put forward for why creativity is important in school’s education were just as relevant for higher education. This work became one of the foundation stones for the Imaginative Curriculum project and network I led for the LTSN and later Higher Education Academy and more recently the work of Creative Academic and #creativeHE.

Ken’s unique contribution was to give creativity a voice: a voice of reason that transcended cultures and systems, a voice that made sense to ordinary people, to teachers and academics working in education, to business leaders and to the politicians that Govern us, who ultimately, are responsible for the target and assessment-driven education system we have created for ourselves. He spoke in clear, forceful, truthful and compelling ways that brought about changes in the ways we understood and valued creativity in its many forms and contexts. In doing these things he gave others the confidence to do these things for themselves. Ken’s untimely death is a great loss to all of us who care about creativity in education but through a life well lived, he has created a wonderful legacy of ideas, writings and recorded talks that will be embodied in the things we do and inspire generations of educators to come. Indeed, this magazine and its open exploration of creativity in order to gain deeper understandings that can inform educational practices, is a concrete manifestation of his values and ideas that enthuse every member of the Creative Academic and #creativeHE community. After I wrote these words I spent several hours browsing some of his youtube recordings ofwhich there are many. It made me realise that because of these recordings and the things he said he has, in some way, become immortal.

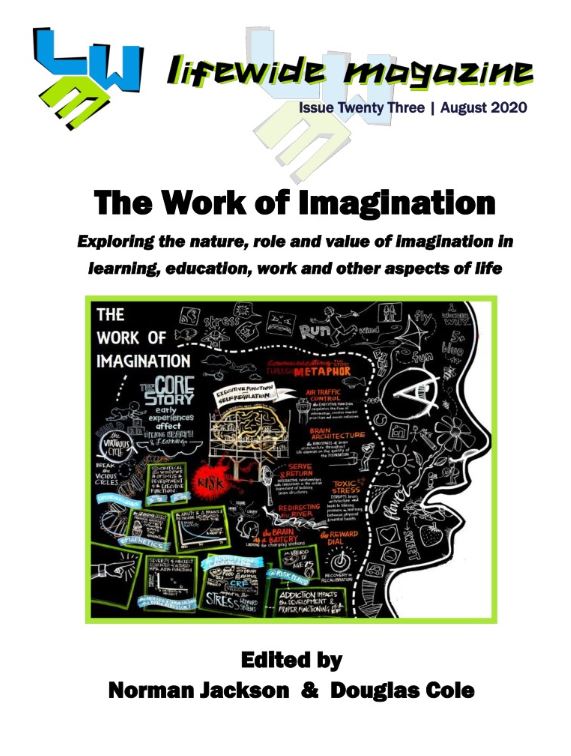

What is the work of imagination?

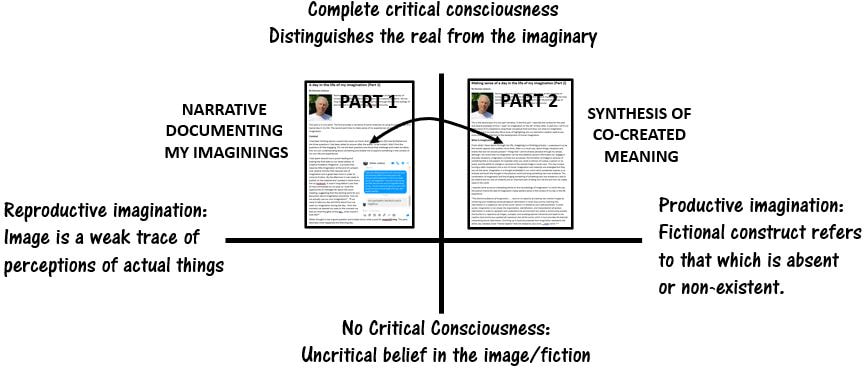

Put simply, the work of imagination is essential to being human. Just imagine a world without imagination. Humans would only develop culturally and technologically in line with what they stumbled across as they lived out their lives. They would not be able to think of things that did not yet exist, nor would they be able to connect up the dots and fill in the missing pieces in their world to understand how things fitted together, nor would they be able to go backwards in time to think about their experiences and draw from them deeper meanings. Humans would not develop and pass on wisdom that comes from their experience and reflecting on what it means without imagination and human civilisations would not be able to ‘advance’ or survive catastrophe without it. We would not have our religions, our art or our science, or stand any chance of tackling the wicked global problems that we encounter – the latest one of which is the pandemic and its social and economic consequences. At a much humbler scale, the magazine and what it contains is the work of many imaginations and it represents a collective attempt to comprehend and make sense of the this wonderful facility that has evolved over billions of years through the growth and replication of life. The magazine is free to download from the Lifewide Education website. https://www.lifewideeducation.uk/magazine.html  Context I had been thinking about a recent discussion on Zoom that Gillian Judson (GJ) had facilitated and the three questions I had been asked to answer after the event. To be honest I didn’t find the questions all that engaging. For me the best questions are those that challenge and make me delve into my own understanding about something and enable me to explore something in the context of my own life and experiences. I had spent several hours proof reading and making the final edits to our latest edition of Creative Academic Magazine(1), on the theme of creative self-expression. Ironically a process that requires little imagination at the end of a project over several months that requires lots of imagination and a great deal more in order to come to fruition. By the afternoon it was ready to publish the magazine on the website and I posted a notice and a link on facebook. It wasn’t long before I saw that GJ had commented on my post so I took the opportunity to message her about the zoom meeting suggesting that it my be more fruitful to explore our own understandings of imagination as we experience it in everyday life. In her response she invited me to write a post about my idea so here is the result of thinking about 'a day in the life of my imagination'.  Part 1 : May 28th A day in my life Scene 1 : Thinking ahead – exploring possibilities It’s just after 6am although I am not aware of the time as I emerge from sleep. I begin to become aware- the lightness and freshness in the room, the window has been open and it’s a little chilly. I can hear the birds singing outside, the distant sound of traffic on the road, and movements in the corridor - my wife I imagine. As I lie semi-aware I start to think about some of the things I will or should do today. I would like to continue with the work in the garden I had begun yesterday – I pictured the area of dead bushes I had taken out and imagined continuing to cut them back, dig out the roots of bramble, add some nourishment to the soil and put down grass seeds. I pictured grass growing where weed infested, twig strewn bare ground now lies and felt a little surge of motivation to continue my project. As my mind began to clear I remembered I am participating in a zoom conference this evening and imagined what it might be like from my past experiences of zoom events. I also visualised the background paper I have to read and the things I have to do to join the event and began to reason when I might do this. A more immediate problem came into my mind. I have to transfer some money to my brother in Australia and it has been a bit of a rigmarole. I tried to do it over the phone yesterday but lacked some information, I know he would have sent it so I imagined myself making this transfer online. Another ‘problem’ came into my mind – I have twin grandsons and its their 8th birthday in 2 days. Their parents are buying them a Nintendo Wii play station. I had promised to buy them a game which I had ordered on Amazon. I am hoping it will arrive today but I don’t have a birthday card so I started thinking about where I might buy a card. Under normal circumstances we would throw a birthday party for the family at the weekend but we are still in lockdown so I imagined going to their house for an hour and sitting in their garden eating some birthday cake. My thoughts then turned to my youngest daughter who is returning to her workplace after 8 weeks working from home during the Covid 19 lockdown. She had lost her accommodation during the crisis and I am helping her look for new accommodation. I had spent several days off and on looking at air B&B but so far she had not booked anything. We had whittled it down to two possible hotels for the first week – one much nicer but considerably more expensive than the other and I tried to see the two possibilities from her perspective imagining what the hotels might be like from the descriptions I had read and the respective journeys to work. Alongside my visualisations I could see my reasoning working away to try to work out what advice I might give her. Perhaps 10 mins had elapsed since I began to wake up but now I am fully awake and so I get out of bed and into the routines I practise everyday. While brushing my teeth I think of the first few minutes of my journey to awareness and realise that even this mundane, nothing special story of a few minutes in my life illustrates just how important and valuable my imagination in to my sense of who I am. Anecdote: It was lunchtime and I was having a sandwich in the garden with one of my daughters. I asked her ‘how did she use her imagination in ordinary everyday settings’. Immediately she volunteered, “I use it to help me get out of bed in the morning”. It transpired that she did exactly what I did in my opening scene to think ahead and build pictures of what she was going to do that day and to help her plan what she might do once she had the picture in her mind (I noticed she used the word picture). We talked about other things, but I thought it was interesting that the first thing that came into her head was also the first thing that came into my consciousness that morning.  Scene 2 : Visualising and implementing change I did indeed get into the garden later in the day to continue what I had started the day before. It was hot and sweat dripped off my forehead as I dug up brambles and other weeds, and cut off dead branches from the conifers before hauling them away for burning. As I toiled I kept thinking about what this much neglected patch of garden might look like in a year when I have levelled the ground, enriched the soil, grown grass and perhaps landscaped it with ferns. I kept visualising a Japanese garden with its twisted conifers and stones. Every time I made a significant cut I tried to visualise what the tree would look like after I had made the cut. As I was working I remembered I had a pile of wood chippings that I can use under the trees. An image of the pile of wood chips at the bottom of the garden came into my mind to give substance to the idea. The image enabled me to see the possibility of using the chips in the change I was trying to bring about and when I had finished my cutting and weeding I did indeed lay down a layer of wood chips under and around the trees. The thought of making a positive difference to this little patch of long neglected ground motivated me to press on. In a few hours of work I saw the difference I had made and it made me feel positive about what I was doing. I am sure that this feeling will sustain me and encourage me to continue transforming this part of the garden.  Scene 3: Exploring ideas – making new meaning My third snapshot of how I used my imagination today is related to my work. I am participating in a year-long inquiry organised by the Learning Innovations Laboratory (LILA) in the education faculty of Harvard University on the theme of learning ecologies. Last October I helped facilitate a two day event in Boston and tonight is the first of two zoom summit events when participants meet to consider the outcomes from the year long inquiry. I had been sent a briefing paper to read and a link to a video I was expected to watch so I spent a chunk of the day reviewing the materials. I jotted down a number of points before identifying a potential theme and imagining by sketching onto a piece of paper, how I could connect or synthesise these points into a bigger and more meaningful picture. The zoom event, a one hour keynote presentation by Ann Pendleton-Jullian and John Seely Brown (two of my favourite thinkers) was scheduled for 8pm my time and I wasn’t disappointed. Their talk was formed around the idea of hyper-connectivity (the infinitely complex interconnectedness and entanglements of people, things, events, wicked problems) that creates a ‘white water world’ full of uncertainty, turbulence, instability and disruption, and how this context requires us to design organisations and our own engagements with the world in new (ecological) ways. What emerged was a powerful exposition of the centrality of human imagination in working with such complexity and the need for humans to develop abilities in abductive reasoning in order to create missing pieces of information in complex informational jigsaw puzzles ‘by imagining and exploring what could possibly be?’ My exposure to these ideas reinforced my belief that these thinkers make an overwhelming case for educational systems to make the development of ‘imagination’ and abductive reasoning a central concern. As I tried to absorb the information I was being given I became excited by the idea of “seeing [imagining] how an object can be changed by connections”(2) I connected this thought in my own mind to the idea of affordance – opportunities to act and to the idea that unique individuals with unique imaginations working in unique contexts see/find unique affordances in the world that has meaning to them. A small but significant insight for me in my ongoing exploration of the idea of ‘learning ecologies’. May 28th A day of creation May 28th was no different to many other days in my life. A lot of mundane stuff happened together with one out-of-the-ordinary event. But looking back it was a day of creation in which I used my imagination to visualise how something might be different and then acted upon this thought to change the something. I consider myself to be a writer so it was not unusual for me to spend time writing but it was a novel experience for me to tell a story about my imagination driven by the belief that the effort involved would pay off in enabling me to gain new insights into how my imagination worked for me. It would be wrong to think of this article as a reflective essay written after the event. The way it was constructed is consistent with Tim Ingold’s view of creativity who says, “to read creativity ‘forwards’, as an improvisatory joining in with formative processes, rather than ‘backwards’, as an abduction from a finished object to an intention in the mind of an agent.” (3) Like creativity, we have to read our imagination forwards as it emerges in particular contexts, acts and circumstances. It is no use seeing the result of our actions that have been inspired by end product and then working backwards to join up the dots. I wrote the article in three sessions on May 28th as the day unfolded and two sessions on the following day. I wrote scene 1 at 8am and wrote my anecdote and scene 2 at 3pm together with the first part of scene 3. Scene 4 was written at 10pm together with most of my sense making (shared in part 2 of my narrative). I did a final read through, edits and additions the next morning before sending my article to GJ. After the article was accepted for the imaginED blog I did some restructuring and edits as the article was divided into two parts and added some additional thoughts to part 2. Although I imagined the idea of telling the story of how I used my imagination during a typical day in my life before Gillian’s invitation to write for the imaginED blog, it was created in response to her invitation. The invitation provided the affordance for me to turn my imagined idea into productive action aimed at producing what I hoped would be a useful artefact. When I emerged from my sleep this morning, the idea was present in my mind and came to life in a conscious imagined thought when I was cleaning my teeth. This thought generated the impulse to act. After making a cup of tea I sat down and tried to remember as much of my waking up as I could. At first it was just a series of notes but then my writer’s imagination began to weave the notes into a story as I gained pleasure from the process of revelation. In part two of my narrative (below) I use several conceptual tools to dig deeper into what my imagination means to me and how I used it on May 28th Sources

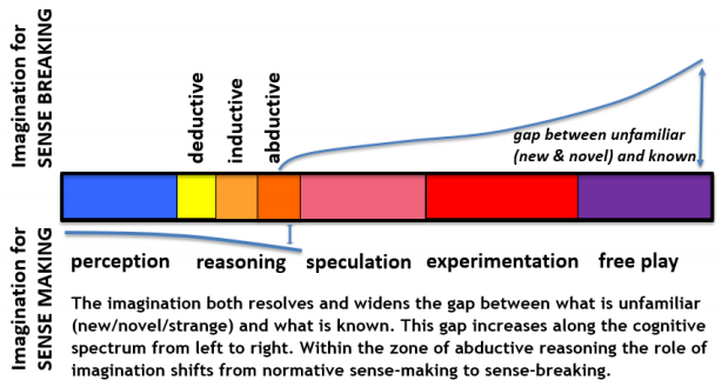

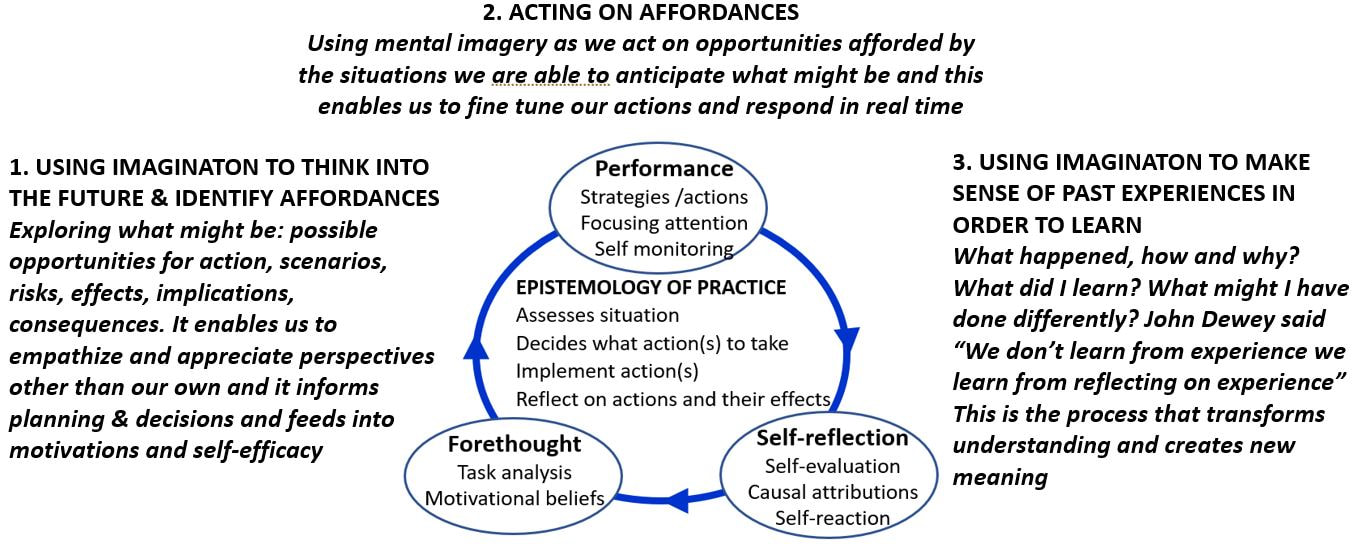

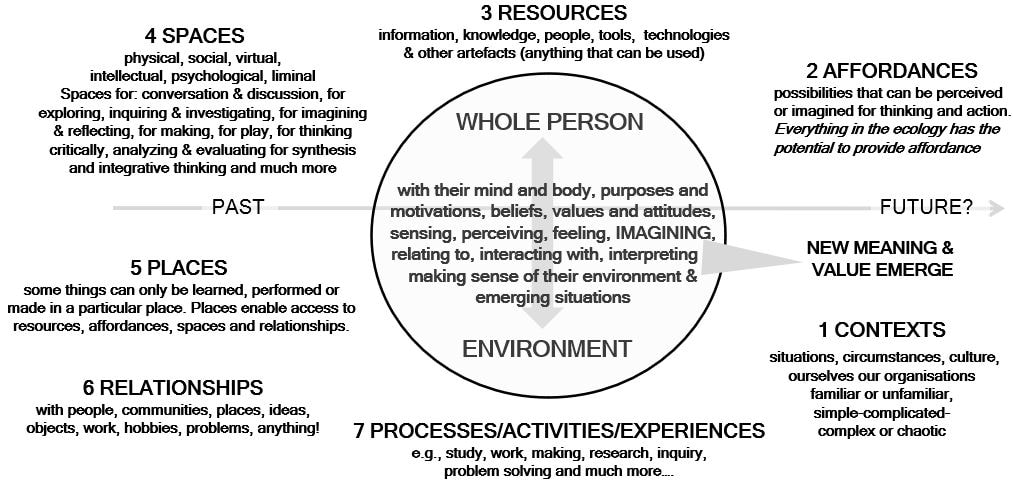

Part 2: Making sense of a day in the life of my imagination What is imagination? Imagining is a thinking process. I understand it to be the mental capacity that enables me to think, often in a visual way, about things, situations and events that are not actually present – things that I cannot directly perceive through my senses, although I am aware that my imagination can be stimulated by sensory information as I engage in everyday situations. Imagination involves two processes, the formation of images or pictures of something that is not present, for example when you recall a memory of a place, a person or an event, and the ability to change or reconstruct the mental image in novel ways. This may involve turning a static impression into a sort of movie. Imagination and creativity are entangled but they are not the same. Imagination is a thought embedded in our mind which sometimes inspires us to embody and enact the thought in the physical world and bring something new into existence. The combination of imagination and the bringing something of something new into existence is said to be creative and our acts of creativity are an important part of being who we are and how we create value in the world. I recently came across an interesting article on the neurobiology of imagination(1) in which the way the authors frame the idea of imagination makes perfect sense in the context of my day in the life experience. “The distinctive feature of imagination…… rests on its capacity of creating new mental images by combining and modifying stored perceptual information in novel ways and by inserting this information in a subjective view of the world: hence it is related to [our] self-awareness. In other words, imagination is not simply the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the environment but rather a constructive process that builds on a repertoire of images, concepts, and autobiographical memories and leads to the creation (and continuous update) of a personal view of the world, which in turn provides the basis for interpreting future information. Summing up it could be proposed that imagination represents the ability [to] create[e] novel “mental objects” that are shaped by [our] own ….inner world.”(1 p2) Journey to understanding my imagination A few years ago, I read a book by Ann Pendleton-Jullian and John Seely Brown(2) (the keynote speakers at the LILA zoom conference mentioned in scene 3 of my narrative), that changed the way I understood the idea of imagination. They outline a concept they called, ‘pragmatic imagination’ suggesting that imagination works with perception and reasoning to enable us to think about things and situations from many different perspectives including perspectives that have never existed. It is this productive entanglement of cognitive and psychological processes – perception, reasoning, imagination, beliefs, values and emotions, that enables us to respond in our unique ways to our unique circumstances through the creation of mental images and models about things that only exist in our thoughts. They illustrated their idea through a diagram that provides a powerful visual aid to understanding the complex relationships and dynamics involved in thinking and I have used this on several occasions to try to understand the relationships between thinking and action where creativity is involved (3,4). Figure 1 The concept of pragmatic imagination and the cognitive spectrum(2) showing how imagination interacts and works with perception and reasoning in a pragmatic way The concept of pragmatic imagination is a tool that can be used to help us think about events and situations that occur in everyday life, like waking up for example described in my day in the life narrative. In thinking about my experience of waking up I can see how the dynamic portrayed in the diagram emerged as I became more aware of myself and my life. While simply lying in bed I could draw on memories of past doings and invent visual representations of possible futures to entertain myself and enjoy certain feelings and engage in planning my immediate future and thinking about the everyday problems and situation I had to deal with. My imagination helped me explore a world that has meaning to me without me being physically involved in the situations I was imagining. When it was integrated with perception and reasoning it enabled me to explore and make sense of possibilities and make decisions about what I might or should do. For example, as I was waking up (scene 1 in my narrative) I imagined the situation in which my daughter is searching for a place to live near where she works. I have been helping her and I used my imagination to put myself in her shoes so to speak, to visualise the choices she had and see the world through her perspective in order that I could give her more useful advice. I also used my imagination it to ’see the possibilities of changing an object by connection’(5) namely, the affordance provided by the half dead conifers to transform this neglected patch of garden into a place that is aesthetically more valuable. As I cut the branches I was conscious that I was picturing in my mind how it would look after I had taken the branch away: I was performing a mental simulation of a future possibility(1) : a simulation that guided my future action. Looking back on this act I sensed my imagination was participating in an act of creative self-expression4 as I tried to change the object in ways that were visually more appealing. I could see the difference I was making as I enacted my vision and this feedback made me feel good. This feeling of positively encouraged me to do more and two days later I built a rockery close to the trees and planted some small juniper bushes to create a mini landscape that was consistent with my image of a Japanese garden. Finally, in scene 3 of my narrative, I experienced an example of using my imagination to explore and see patterns in information and ideas to reach a sort of synthesis (a novel configuration of ideas) that provided me with questions for further inquiry. This process continued in the production of this artefact - an act of creative self-expression in its own right, and in the productive entanglement of perception, reasoning and imagination that enabled me to see and use the affordance in my story to understand what my imagination means and to share my sense making through this post on the imaginED blog. Reproductive and productive imagination Which brings me to the ideas of Paul Ricoeur. In her excellent book, ‘Fostering Imagination in Higher Education,’(6) Joy Whitton provides another useful conceptual tool (Figure 2). Drawing on the philosophical work of Paul Ricoeur(7), she draws attention to the distinction he makes between reproductive and productive imagination. “Ricoeur draws a distinction between ‘reproductive’ imagination, which relies on memory and mimesis, and ‘productive’ imagination, which is generative. He asserts there are two main types of reproductive imagination: the first refers to the way we bring common objects or experiences to the ‘mind’s eye’ in the form of an image. The second refers to material representations whose function is to somehow copy or ‘take the place of’ the things they represent (e.g., photographs, portraits, drawings, diagrams, and maps).” (6 citing 7) Figure 2 My attempt to use Paul Ricoeur’s conceptual framework(7) as a tool to understand the role of imagination in the artefacts I created to try to understand my imagination. Relating these ideas to my narrative, I drew on my reproductive imagination as I woke up on May 28th and thought about several things I had to do during the day, soon after this event I sat down at my desk and made a material representation in the form of describing through writing some of the things I had thought. Ricoeur suggests that reproductive forms of imagination tend to be less illuminating in terms of understanding human action, agency, and creativity because they merely reproduce the perceived world. His focus is on ‘productive’ imagination, embodied in inventions like novels and fables – which are not intended to be straightforward descriptions of the world. Hence, they cannot be categorized as correct or incorrect accounts of reality because they imply a consciousness of the fictiveness of the account.(7 citing 8) “[Ricoeur] argues that creating a story is an act of semantic innovation. In narrative, the semantic innovation lies in the inventing of another work of recombination and synthesis. The productive imagination ‘grasps together and integrates into one whole and complete story multiple and scattered events, thereby schematizing the intelligible signification attached to the narrative taken as a whole’. ‘To understand the story is to understand how and why the successive episodes led to this conclusion, which, far from being foreseeable, must finally be acceptable, as congruent with the episodes brought together by the story’.” (6 citing 7) Whitton argues that productive imagination is often a co-created phenomenon as the ideas that one person shares through language/writing/symbols and other means engage the imagination and intellect of another: let’s call this our pragmatic imagination to bring together our perception, reasoning and imagination in productive partnership. When I combined my descriptive narrative of how my imagination emerged on May 28th with this evaluative commentary, I drew on and made productive use of the conceptual tools and thinking of others. I must acknowledge that my productive imagination is a co-created phenomenon. By sharing my understandings through the imagined blog, my ways of thinking about imagination might in time be incorporated into the reader’s meaning making. Connecting my imagination and creativity Earlier I made the point that imagination and creativity are entangled but they are not the same. Imagination creates the impulse to act by enabling us to see something differently (to search for and discover novelty) and through the revelations it brings we are engaged emotionally. When pragmatically connected to perceptions and reasoning it helps us plan how to act and it enables us to understand whether what we might do is within our capabilities (self-efficacy). My narrative explains how the thoughts that emerged on an ordinary day through the work of my pragmatic imagination led to action which transformed existing things (e.g. the neglected patch of my garden) and produced new things (this story and its explanation for example). Without the capability to imagine in the contexts I inhabit I could not be me. That is being me in the contexts of my role as a husband, father, grandfather and friend, or being me in my work as an educator and scholar trying to contribute to my field of practice and domain of knowledge. I might speculate that my use of imagination when connected to actions that are directed to enacting my imagination in these different contexts of my life is analogous to the little-c (everyday acts of creativity) and Pro-c (creativity in domains of expertise) in the widely accepted 4C model of creativity(8). James Kaufman and Ron Beghetto, the originators of the 4C model of creativity, refer to mini-c as the cognitive and emotional process of constructing personal knowledge within a particular sociocultural context in order to develop/change understanding. “It is a mental process found in all stages of human development and activity, from the imaginings of a child that transforms his everyday world into a magical and mysterious world of giants and monsters, to the most sophisticated conceptual thinking necessary for breakthrough science, mini-c creativity is not just for kids. Rather, it represents the initial, creative interpretations that all creators have and which later may manifest into recognizable (and in some instances, historically celebrated) creations” (8 p4) It has taken me a long time to realise that my imagination working pragmatically with perception and reasoning is the mini-c referred to in their 4C model and I can now make an incremental change to the norms and contexts conceptual framework I developed(9) (Figure 4) to reflect this change in my own understanding. This is another example of “seeing an object and imagining how it might be changed through connection.”(6) Figure 3 Contexts and norms framework for creativity developed by Jackson and Lassig (9) from the 4C model of creativity (8) Imagination and practice It is clear from my narrative that I consider imagination is central to our ability to practice. I can demonstrate this by reference to what Michael Eraut calls the epistemology of practice(11) or Barry Zimmerman calls self-regulation(12) : the essential processes we enact whenever we want to do something significant. Figure 4 attempts to illustrate these theoretical models and show that imagination, connected to perception and reasoning is important in all aspects of these models. Figure 4 How imagination is used in two holistic models of practice. Michael Eraut’s epistemology of practice(11) and Barry Zimmerman’s model of self-regulation(12) This conceptual tool helps us to see that our imagination facilitates exploration of possibilities (affordances) in future-oriented thinking by encouraging us to think through questions like, ‘what if?’ and ‘what is or might be possible? Once we engage in action our imagination is stimulated by the feedback we receive from the environment and our effects on it and it helps us anticipate ‘the next move’. It also participates in the sense making and the invention of new syntheses and meanings in reflective and reflexive thinking that revisits information, knowledge and emotion gained from action and experience and prompts us to engage not only with ‘what happened and why?’ but alternative possibilities e.g. ‘what if I had done this?’ John Dewey once said, “we don’t learn from experience, we learn from reflecting on experience” (13 p.78). It is this process that transforms our understanding and I now see reflection as a process involving pragmatic imagination. Imagining ecologies for learning and practice The contemporary hyperconnected, contingent world in rapid formation4 demands an ecological mindset: a mindset through which we might better see (perceive and imagine) and understand the connectivity and relatedness of ourselves and the world that has meaning to us. I have argued (13, 14, 4) that we need new frameworks to help us ‘see’ (perceive, feel, reason and imagine), relate to and interact with the world in order to learn and practice. Figure 5 provides such an ecological framework. It relates a whole thinking, feeling, acting, caring person to their contexts, their needs, desires and purposes, and what they are trying to achieve in the particular situations in which they are acting and learning. When someone encounters a new challenge or opportunity, they attempt to comprehend (see with their senses and imagination) the situation and act in appropriate and perhaps novel ways. Effectively, they create an ecology that enables them to perceive and interact with their environment in order to accomplish the things that matter to them and learning and achievement emerge from this dynamic. In this way, the person, their environment and their activities are not only connected and related – they are unified. ‘Every organism has an environment: the organism shapes its environment and environment shapes the organism. So it helps to think of an indivisible totality of “organism plus environment” - best seen as an ongoing process of growth and development.’ (16 p. 20) “When we experience something, we act upon it, we do something with it; then we suffer or undergo the consequences. We do something to the thing and then it does something to us in return” (17 p46) Figure 5 An ecology for learning and practice ecology (15 p86) : a framework for visualising the components, relationships and exchanges between a person and their environment in order to learn and practise. Labels (1-7) explain the key dimensions of the ecology. A learning ecology is an ecology of practice in which the primary purpose is learning. The same framework can be used to characterise any complex practice where learning is intended to achieve something significant. An ecology for learning and practice enables the creator to put their pragmatic imagination to work in the world that has meaning to engage with situations, problems and opportunities as they emerge in their unique circumstances. Such an ecology enables the maker to ‘see’ (through their pragmatic imaginations) the affordances in their world and to act upon these affordances within their capabilities, and to extend their capabilities through their actions. Such an ecology enables the maker to connect and integrate different spaces, resources, tools, situations, relationships, activities and themselves in ways that they find meaningful, and effect various transformations (personal, material and virtual). Such an ecology enables the maker to connect and integrate their past, present and future, and connect thoughts and actions experienced in a moment and organise them into more significant meaningful experiences of thinking and action. They are the means by which the maker weaves their moments into the fabric of a meaningful life, a life they feel is worth living and a life through which they can grow and develop as a person. The components of an ecology for learning, (summarised in Figure 5) are woven together by the maker in a part deliberate, part opportunistic, act of trying to achieve something and learn in the process. They do not stand in isolation: they can and do connect and interfere and become incorporated into other learning ecologies. An ecology for learning and practice enables the maker to think and act in an ecological (connected, relational and integrated) way, to perceive (observe, sense and comprehend the information flows), and to imagine through the creation of mental imagery what might be and what might be transformed in order to create new meanings, things and situations. And when their work is done they enable the maker to reflect on what has been experienced to make better sense of it and learn from the experience. This article is the material and creative expression from such an ecology for learning and practice. It began with an imagined thought in the wake of an experience (my zoom meeting with the imaginED network). It was given meaning and expression as I enacted this thought on May 28th, seeing and acting upon the affordances in my life and responding to what emerged. It continued as I engaged my [pragmatic] imagination during and after living and experiencing that day in order to make deeper sense of my experience. The meaning making that is shared through this article has been co-created with all the people whose ideas and imaginations I have woven into this synthesis (my list of citations and more). Why should imagination and creativity be a central concern for education? Sometimes the most ordinary situations and experiences in life can reveal important truths. Through my simple story recording some of the ways in which my imagination emerged and influenced my actions on May 28th I have tried to show how important it is to who we are – our being and our becoming. Furthermore, our cultures and everything we have made in them are the product of imagination connected to perception and reasoning, enacted in ways that give meaning and substance to our thoughts. So when asked a question like, why should education be concerned with nurturing and developing the imaginations of learners? – the simple answer is that without their imaginations they cannot function as creative, empathic, caring and productive human beings and neither can our human civilisations. If imagination and creativity are so important to human flourishing from the level of individuals to whole societies then our educational systems need to be reconfigured to reflect this profound truth. I have tried to show, in a variety of ways, that imagination acting in concert with perception, reasoning and the psychological spectrum of emotions (an expanded pragmatic imagination 2) is crucial to effective practice in a hyperconnected, contingent, world in continuous formation. And that we can locate imagination and the work is does in a number of credible epistemological, ontological and ecological conceptual frameworks. Our systems of education have a moral and practical obligation to help learners develop their imaginations so that they can fully participate in this fast forming and emergent world. Furthermore, if we want learners to make a positive difference to their world, to create new value and transform it in yet to be imagined ways, we need them to use and develop their imaginations not only in the context of their academic programmes but in the multitude of contexts from which their life is formed. This supposes that our education systems will be founded up on a lifewide concept of learning, developing and achieving (18,19) and we will universally recognise the importance of the educational domain in encouraging the development and use of imagination and creativity (9) (Figure 6). Figure 6 A model of imagination and creativity that recognises and values the educational domain(9) In this version of the model I have substituted the concept of pragmatic imagination(2) for what Kaufman and Beghetto call mini-c(9) to emphasise the reciprocal and synergistic nature of these two phenomena. Sources

10 Eraut, M. & Hirsh, W.(2008) Significance of Workplace Learning for Individuals, Groups & Organisations 11 Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). “Attaining self-regulation: a social cognitive perspective,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation, eds M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 13–40 12 Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think, New York: D. C. Heath 13 Jackson, N.J. (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies, Chalk Mountain LULU 14 Barnett, R. and Jackson, N.J. (eds) Ecologies of Learning and Practice: Emerging Ideas, Sightings and Possibilities Routledge 15 Jackson, N.J. (2020) Higher Education Ecosystems and the Ecologies for Learning and Practice they Encourage and Support. In R. Barnett and N.J. Jackson (eds) Ecologies of Learning and Practice: Emerging Ideas, Sightings and Possibilities Routledge 16 Ingold, T. (2000) Hunting and gathering as ways of perceiving the environment. The Perception of the Environment. Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. New York and London: Routledge, 2000 17 Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Penguin. 18 Jackson N.J, et al (Eds) Learning for a Complex World: A Lifewide Concept of Learning, Education and Development. Authorhouse 19 https://www.lifewideeducation.uk/ How playing on a beach helped me develop a profiling tool for creativity It never ceases to amaze me how one act can lead to entirely different acts that we could not begin to imagine from the starting point of our journey. Early in March before Covid struck, my wife and I spent a very happy 10 days meandering up the NW side of Scotland. I have to say that the west coast of Scotland is one of the most beautiful places and spaces I have had the good fortune to find myself in. As we journeyed through the stunning coastal landscape I felt the need to leave my mark so I made some simple towers of stones from the rocks that were ready to hand in some of the places we visited. And for a few moments I felt a part of the landscape. I photographed the towers and later made a short movie. A few weeks later I used my experience as an illustration of creative self-expression and this evolved into writing the story which that I then used to evaluate my own creativity and develop some new mapping and profiling tools in the process. I think these tools might be useful in educational settings and I welcome others to try them out. You can read the story below and download the tool profiling here http://www.normanjackson.co.uk/creativejam.html

|

PurposeTo develop my understandings of how I learn and develop through all parts of my life by recording and reflecting on my own life as it happens. I have a rough plan but most of what I do emerges from the circumstances of my life

Archive

January 2021

Categories

|

||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed