I had been thinking about a recent discussion on Zoom that Gillian Judson (GJ) had facilitated and the three questions I had been asked to answer after the event. To be honest I didn’t find the questions all that engaging. For me the best questions are those that challenge and make me delve into my own understanding about something and enable me to explore something in the context of my own life and experiences. I had spent several hours proof reading and making the final edits to our latest edition of Creative Academic Magazine(1), on the theme of creative self-expression. Ironically a process that requires little imagination at the end of a project over several months that requires lots of imagination and a great deal more in order to come to fruition. By the afternoon it was ready to publish the magazine on the website and I posted a notice and a link on facebook. It wasn’t long before I saw that GJ had commented on my post so I took the opportunity to message her about the zoom meeting suggesting that it my be more fruitful to explore our own understandings of imagination as we experience it in everyday life. In her response she invited me to write a post about my idea so here is the result of thinking about 'a day in the life of my imagination'.

Scene 1 : Thinking ahead – exploring possibilities

It’s just after 6am although I am not aware of the time as I emerge from sleep. I begin to become aware- the lightness and freshness in the room, the window has been open and it’s a little chilly. I can hear the birds singing outside, the distant sound of traffic on the road, and movements in the corridor - my wife I imagine.

As I lie semi-aware I start to think about some of the things I will or should do today. I would like to continue with the work in the garden I had begun yesterday – I pictured the area of dead bushes I had taken out and imagined continuing to cut them back, dig out the roots of bramble, add some nourishment to the soil and put down grass seeds. I pictured grass growing where weed infested, twig strewn bare ground now lies and felt a little surge of motivation to continue my project.

As my mind began to clear I remembered I am participating in a zoom conference this evening and imagined what it might be like from my past experiences of zoom events. I also visualised the background paper I have to read and the things I have to do to join the event and began to reason when I might do this.

A more immediate problem came into my mind. I have to transfer some money to my brother in Australia and it has been a bit of a rigmarole. I tried to do it over the phone yesterday but lacked some information, I know he would have sent it so I imagined myself making this transfer online.

Another ‘problem’ came into my mind – I have twin grandsons and its their 8th birthday in 2 days. Their parents are buying them a Nintendo Wii play station. I had promised to buy them a game which I had ordered on Amazon. I am hoping it will arrive today but I don’t have a birthday card so I started thinking about where I might buy a card. Under normal circumstances we would throw a birthday party for the family at the weekend but we are still in lockdown so I imagined going to their house for an hour and sitting in their garden eating some birthday cake.

My thoughts then turned to my youngest daughter who is returning to her workplace after 8 weeks working from home during the Covid 19 lockdown. She had lost her accommodation during the crisis and I am helping her look for new accommodation. I had spent several days off and on looking at air B&B but so far she had not booked anything. We had whittled it down to two possible hotels for the first week – one much nicer but considerably more expensive than the other and I tried to see the two possibilities from her perspective imagining what the hotels might be like from the descriptions I had read and the respective journeys to work. Alongside my visualisations I could see my reasoning working away to try to work out what advice I might give her.

Perhaps 10 mins had elapsed since I began to wake up but now I am fully awake and so I get out of bed and into the routines I practise everyday. While brushing my teeth I think of the first few minutes of my journey to awareness and realise that even this mundane, nothing special story of a few minutes in my life illustrates just how important and valuable my imagination in to my sense of who I am.

Anecdote: It was lunchtime and I was having a sandwich in the garden with one of my daughters. I asked her ‘how did she use her imagination in ordinary everyday settings’. Immediately she volunteered, “I use it to help me get out of bed in the morning”. It transpired that she did exactly what I did in my opening scene to think ahead and build pictures of what she was going to do that day and to help her plan what she might do once she had the picture in her mind (I noticed she used the word picture). We talked about other things, but I thought it was interesting that the first thing that came into her head was also the first thing that came into my consciousness that morning.

I did indeed get into the garden later in the day to continue what I had started the day before. It was hot and sweat dripped off my forehead as I dug up brambles and other weeds, and cut off dead branches from the conifers before hauling them away for burning. As I toiled I kept thinking about what this much neglected patch of garden might look like in a year when I have levelled the ground, enriched the soil, grown grass and perhaps landscaped it with ferns.

I kept visualising a Japanese garden with its twisted conifers and stones. Every time I made a significant cut I tried to visualise what the tree would look like after I had made the cut. As I was working I remembered I had a pile of wood chippings that I can use under the trees. An image of the pile of wood chips at the bottom of the garden came into my mind to give substance to the idea. The image enabled me to see the possibility of using the chips in the change I was trying to bring about and when I had finished my cutting and weeding I did indeed lay down a layer of wood chips under and around the trees.

The thought of making a positive difference to this little patch of long neglected ground motivated me to press on. In a few hours of work I saw the difference I had made and it made me feel positive about what I was doing. I am sure that this feeling will sustain me and encourage me to continue transforming this part of the garden.

My third snapshot of how I used my imagination today is related to my work. I am participating in a year-long inquiry organised by the Learning Innovations Laboratory (LILA) in the education faculty of Harvard University on the theme of learning ecologies.

Last October I helped facilitate a two day event in Boston and tonight is the first of two zoom summit events when participants meet to consider the outcomes from the year long inquiry. I had been sent a briefing paper to read and a link to a video I was expected to watch so I spent a chunk of the day reviewing the materials. I jotted down a number of points before identifying a potential theme and imagining by sketching onto a piece of paper, how I could connect or synthesise these points into a bigger and more meaningful picture.

The zoom event, a one hour keynote presentation by Ann Pendleton-Jullian and John Seely Brown (two of my favourite thinkers) was scheduled for 8pm my time and I wasn’t disappointed. Their talk was formed around the idea of hyper-connectivity (the infinitely complex interconnectedness and entanglements of people, things, events, wicked problems) that creates a ‘white water world’ full of uncertainty, turbulence, instability and disruption, and how this context requires us to design organisations and our own engagements with the world in new (ecological) ways.

What emerged was a powerful exposition of the centrality of human imagination in working with such complexity and the need for humans to develop abilities in abductive reasoning in order to create missing pieces of information in complex informational jigsaw puzzles ‘by imagining and exploring what could possibly be?’ My exposure to these ideas reinforced my belief that these thinkers make an overwhelming case for educational systems to make the development of ‘imagination’ and abductive reasoning a central concern.

As I tried to absorb the information I was being given I became excited by the idea of “seeing [imagining] how an object can be changed by connections”(2) I connected this thought in my own mind to the idea of affordance – opportunities to act and to the idea that unique individuals with unique imaginations working in unique contexts see/find unique affordances in the world that has meaning to them. A small but significant insight for me in my ongoing exploration of the idea of ‘learning ecologies’.

May 28th was no different to many other days in my life. A lot of mundane stuff happened together with one out-of-the-ordinary event. But looking back it was a day of creation in which I used my imagination to visualise how something might be different and then acted upon this thought to change the something.

I consider myself to be a writer so it was not unusual for me to spend time writing but it was a novel experience for me to tell a story about my imagination driven by the belief that the effort involved would pay off in enabling me to gain new insights into how my imagination worked for me.

It would be wrong to think of this article as a reflective essay written after the event. The way it was constructed is consistent with Tim Ingold’s view of creativity who says, “to read creativity ‘forwards’, as an improvisatory joining in with formative processes, rather than ‘backwards’, as an abduction from a finished object to an intention in the mind of an agent.” (3) Like creativity, we have to read our imagination forwards as it emerges in particular contexts, acts and circumstances. It is no use seeing the result of our actions that have been inspired by end product and then working backwards to join up the dots.

I wrote the article in three sessions on May 28th as the day unfolded and two sessions on the following day. I wrote scene 1 at 8am and wrote my anecdote and scene 2 at 3pm together with the first part of scene 3. Scene 4 was written at 10pm together with most of my sense making (shared in part 2 of my narrative). I did a final read through, edits and additions the next morning before sending my article to GJ. After the article was accepted for the imaginED blog I did some restructuring and edits as the article was divided into two parts and added some additional thoughts to part 2.

Although I imagined the idea of telling the story of how I used my imagination during a typical day in my life before Gillian’s invitation to write for the imaginED blog, it was created in response to her invitation. The invitation provided the affordance for me to turn my imagined idea into productive action aimed at producing what I hoped would be a useful artefact. When I emerged from my sleep this morning, the idea was present in my mind and came to life in a conscious imagined thought when I was cleaning my teeth. This thought generated the impulse to act. After making a cup of tea I sat down and tried to remember as much of my waking up as I could. At first it was just a series of notes but then my writer’s imagination began to weave the notes into a story as I gained pleasure from the process of revelation.

In part two of my narrative (below) I use several conceptual tools to dig deeper into what my imagination means to me and how I used it on May 28th

Sources

- Exploring and Celebrating Creative Self-Expression. Creative Academic Magazine #16 available at: https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

- An idea shared by Ann Pendleton-Jullian in her zoom talk on May 28th The idea is from Joshua Cooper Ramos’ book The Seventh Sense: Power, Fortune, and Survival in the Age of Networks Little Brown and Company Boston (2016). “The seventh sense, in short, is the ability to look at any object and see the way in which it is changed by connection.”

- Ingold T (2010) Bringing Things to Life: Creative Entanglements in a World of Materials.

Part 2: Making sense of a day in the life of my imagination

What is imagination?

Imagining is a thinking process. I understand it to be the mental capacity that enables me to think, often in a visual way, about things, situations and events that are not actually present – things that I cannot directly perceive through my senses, although I am aware that my imagination can be stimulated by sensory information as I engage in everyday situations. Imagination involves two processes, the formation of images or pictures of something that is not present, for example when you recall a memory of a place, a person or an event, and the ability to change or reconstruct the mental image in novel ways. This may involve turning a static impression into a sort of movie. Imagination and creativity are entangled but they are not the same. Imagination is a thought embedded in our mind which sometimes inspires us to embody and enact the thought in the physical world and bring something new into existence. The combination of imagination and the bringing something of something new into existence is said to be creative and our acts of creativity are an important part of being who we are and how we create value in the world.

I recently came across an interesting article on the neurobiology of imagination(1) in which the way the authors frame the idea of imagination makes perfect sense in the context of my day in the life experience.

“The distinctive feature of imagination…… rests on its capacity of creating new mental images by combining and modifying stored perceptual information in novel ways and by inserting this information in a subjective view of the world: hence it is related to [our] self-awareness. In other words, imagination is not simply the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the environment but rather a constructive process that builds on a repertoire of images, concepts, and autobiographical memories and leads to the creation (and continuous update) of a personal view of the world, which in turn provides the basis for interpreting future information. Summing up it could be proposed that imagination represents the ability [to] create[e] novel “mental objects” that are shaped by [our] own ….inner world.”(1 p2)

Journey to understanding my imagination

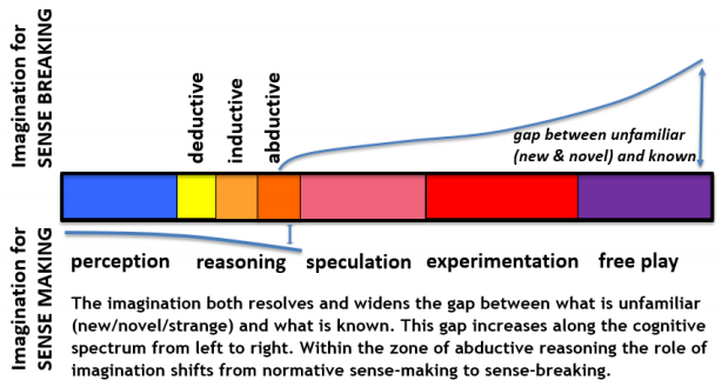

A few years ago, I read a book by Ann Pendleton-Jullian and John Seely Brown(2) (the keynote speakers at the LILA zoom conference mentioned in scene 3 of my narrative), that changed the way I understood the idea of imagination. They outline a concept they called, ‘pragmatic imagination’ suggesting that imagination works with perception and reasoning to enable us to think about things and situations from many different perspectives including perspectives that have never existed. It is this productive entanglement of cognitive and psychological processes – perception, reasoning, imagination, beliefs, values and emotions, that enables us to respond in our unique ways to our unique circumstances through the creation of mental images and models about things that only exist in our thoughts. They illustrated their idea through a diagram that provides a powerful visual aid to understanding the complex relationships and dynamics involved in thinking and I have used this on several occasions to try to understand the relationships between thinking and action where creativity is involved (3,4).

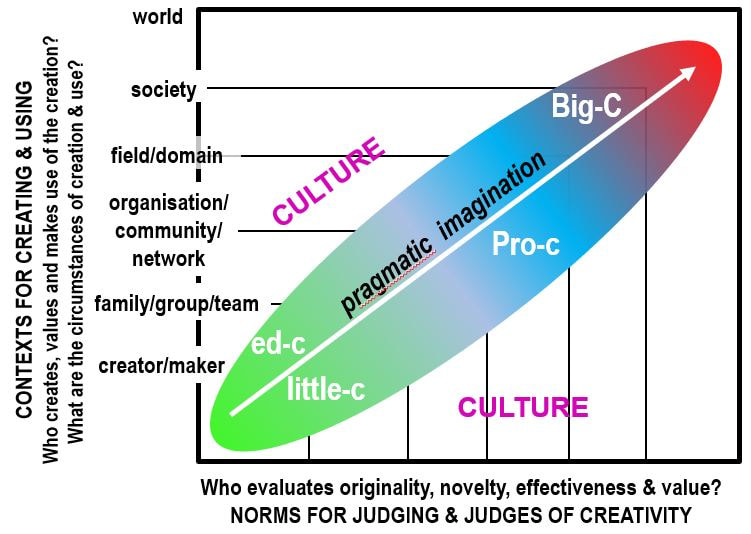

Figure 1 The concept of pragmatic imagination and the cognitive spectrum(2) showing how imagination interacts and works with perception and reasoning in a pragmatic way

The concept of pragmatic imagination is a tool that can be used to help us think about events and situations that occur in everyday life, like waking up for example described in my day in the life narrative. In thinking about my experience of waking up I can see how the dynamic portrayed in the diagram emerged as I became more aware of myself and my life. While simply lying in bed I could draw on memories of past doings and invent visual representations of possible futures to entertain myself and enjoy certain feelings and engage in planning my immediate future and thinking about the everyday problems and situation I had to deal with.

My imagination helped me explore a world that has meaning to me without me being physically involved in the situations I was imagining. When it was integrated with perception and reasoning it enabled me to explore and make sense of possibilities and make decisions about what I might or should do. For example, as I was waking up (scene 1 in my narrative) I imagined the situation in which my daughter is searching for a place to live near where she works. I have been helping her and I used my imagination to put myself in her shoes so to speak, to visualise the choices she had and see the world through her perspective in order that I could give her more useful advice.

I also used my imagination it to ’see the possibilities of changing an object by connection’(5) namely, the affordance provided by the half dead conifers to transform this neglected patch of garden into a place that is aesthetically more valuable. As I cut the branches I was conscious that I was picturing in my mind how it would look after I had taken the branch away: I was performing a mental simulation of a future possibility(1) : a simulation that guided my future action. Looking back on this act I sensed my imagination was participating in an act of creative self-expression4 as I tried to change the object in ways that were visually more appealing. I could see the difference I was making as I enacted my vision and this feedback made me feel good. This feeling of positively encouraged me to do more and two days later I built a rockery close to the trees and planted some small juniper bushes to create a mini landscape that was consistent with my image of a Japanese garden.

Finally, in scene 3 of my narrative, I experienced an example of using my imagination to explore and see patterns in information and ideas to reach a sort of synthesis (a novel configuration of ideas) that provided me with questions for further inquiry. This process continued in the production of this artefact - an act of creative self-expression in its own right, and in the productive entanglement of perception, reasoning and imagination that enabled me to see and use the affordance in my story to understand what my imagination means and to share my sense making through this post on the imaginED blog.

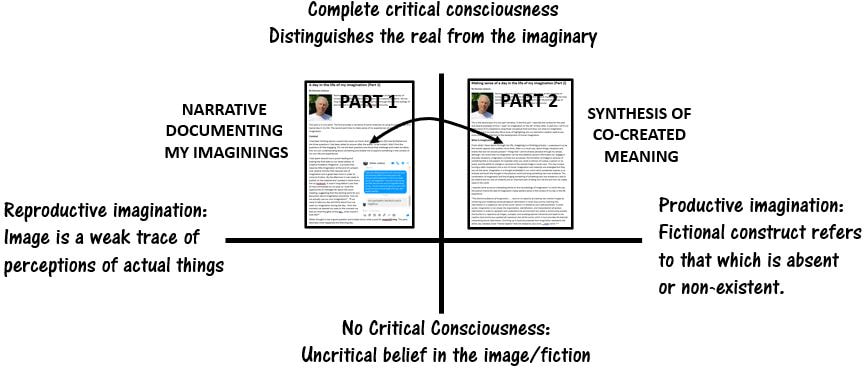

Reproductive and productive imagination

Which brings me to the ideas of Paul Ricoeur. In her excellent book, ‘Fostering Imagination in Higher Education,’(6) Joy Whitton provides another useful conceptual tool (Figure 2). Drawing on the philosophical work of Paul Ricoeur(7), she draws attention to the distinction he makes between reproductive and productive imagination.

“Ricoeur draws a distinction between ‘reproductive’ imagination, which relies on memory and mimesis, and ‘productive’ imagination, which is generative. He asserts there are two main types of reproductive imagination: the first refers to the way we bring common objects or experiences to the ‘mind’s eye’ in the form of an image. The second refers to material representations whose function is to somehow copy or ‘take the place of’ the things they represent (e.g., photographs, portraits, drawings, diagrams, and maps).” (6 citing 7)

Figure 2 My attempt to use Paul Ricoeur’s conceptual framework(7) as a tool to understand the role of imagination in the artefacts I created to try to understand my imagination.

Relating these ideas to my narrative, I drew on my reproductive imagination as I woke up on May 28th and thought about several things I had to do during the day, soon after this event I sat down at my desk and made a material representation in the form of describing through writing some of the things I had thought. Ricoeur suggests that reproductive forms of imagination tend to be less illuminating in terms of understanding human action, agency, and creativity because they merely reproduce the perceived world. His focus is on ‘productive’ imagination, embodied in inventions like novels and fables – which are not intended to be straightforward descriptions of the world. Hence, they cannot be categorized as correct or incorrect accounts of reality because they imply a consciousness of the fictiveness of the account.(7 citing 8)

“[Ricoeur] argues that creating a story is an act of semantic innovation. In narrative, the semantic innovation lies in the inventing of another work of recombination and synthesis. The productive imagination ‘grasps together and integrates into one whole and complete story multiple and scattered events, thereby schematizing the intelligible signification attached to the narrative taken as a whole’. ‘To understand the story is to understand how and why the successive episodes led to this conclusion, which, far from being foreseeable, must finally be acceptable, as congruent with the episodes brought together by the story’.” (6 citing 7)

Whitton argues that productive imagination is often a co-created phenomenon as the ideas that one person shares through language/writing/symbols and other means engage the imagination and intellect of another: let’s call this our pragmatic imagination to bring together our perception, reasoning and imagination in productive partnership. When I combined my descriptive narrative of how my imagination emerged on May 28th with this evaluative commentary, I drew on and made productive use of the conceptual tools and thinking of others. I must acknowledge that my productive imagination is a co-created phenomenon. By sharing my understandings through the imagined blog, my ways of thinking about imagination might in time be incorporated into the reader’s meaning making.

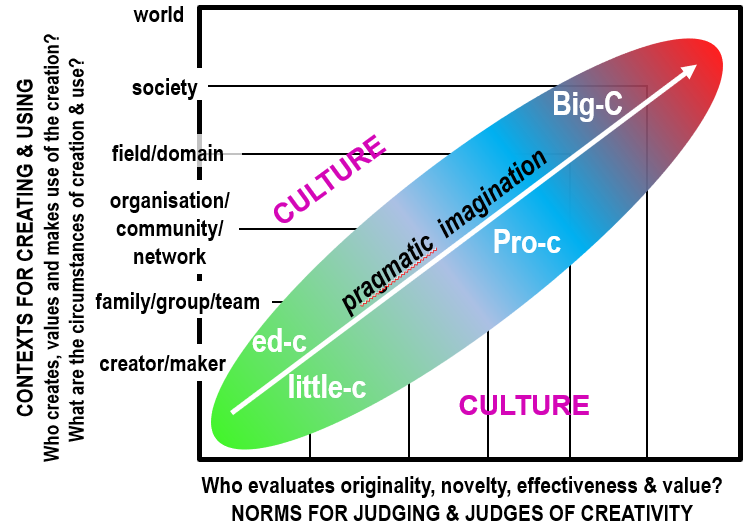

Earlier I made the point that imagination and creativity are entangled but they are not the same. Imagination creates the impulse to act by enabling us to see something differently (to search for and discover novelty) and through the revelations it brings we are engaged emotionally. When pragmatically connected to perceptions and reasoning it helps us plan how to act and it enables us to understand whether what we might do is within our capabilities (self-efficacy). My narrative explains how the thoughts that emerged on an ordinary day through the work of my pragmatic imagination led to action which transformed existing things (e.g. the neglected patch of my garden) and produced new things (this story and its explanation for example). Without the capability to imagine in the contexts I inhabit I could not be me. That is being me in the contexts of my role as a husband, father, grandfather and friend, or being me in my work as an educator and scholar trying to contribute to my field of practice and domain of knowledge. I might speculate that my use of imagination when connected to actions that are directed to enacting my imagination in these different contexts of my life is analogous to the little-c (everyday acts of creativity) and Pro-c (creativity in domains of expertise) in the widely accepted 4C model of creativity(8).

James Kaufman and Ron Beghetto, the originators of the 4C model of creativity, refer to mini-c as the cognitive and emotional process of constructing personal knowledge within a particular sociocultural context in order to develop/change understanding. “It is a mental process found in all stages of human development and activity, from the imaginings of a child that transforms his everyday world into a magical and mysterious world of giants and monsters, to the most sophisticated conceptual thinking necessary for breakthrough science, mini-c creativity is not just for kids. Rather, it represents the initial, creative interpretations that all creators have and which later may manifest into recognizable (and in some instances, historically celebrated) creations” (8 p4) It has taken me a long time to realise that my imagination working pragmatically with perception and reasoning is the mini-c referred to in their 4C model and I can now make an incremental change to the norms and contexts conceptual framework I developed(9) (Figure 4) to reflect this change in my own understanding. This is another example of “seeing an object and imagining how it might be changed through connection.”(6)

Figure 3 Contexts and norms framework for creativity developed by Jackson and Lassig (9) from the 4C model of creativity (8)

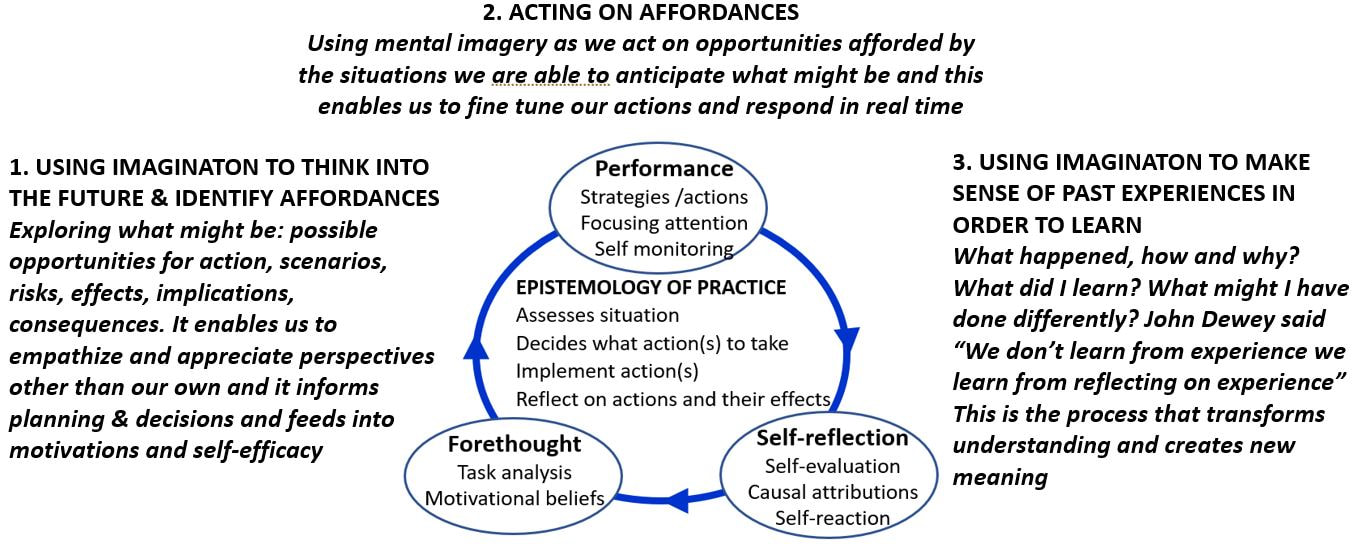

It is clear from my narrative that I consider imagination is central to our ability to practice. I can demonstrate this by reference to what Michael Eraut calls the epistemology of practice(11) or Barry Zimmerman calls self-regulation(12) : the essential processes we enact whenever we want to do something significant. Figure 4 attempts to illustrate these theoretical models and show that imagination, connected to perception and reasoning is important in all aspects of these models.

Figure 4 How imagination is used in two holistic models of practice. Michael Eraut’s epistemology of practice(11) and Barry Zimmerman’s model of self-regulation(12)

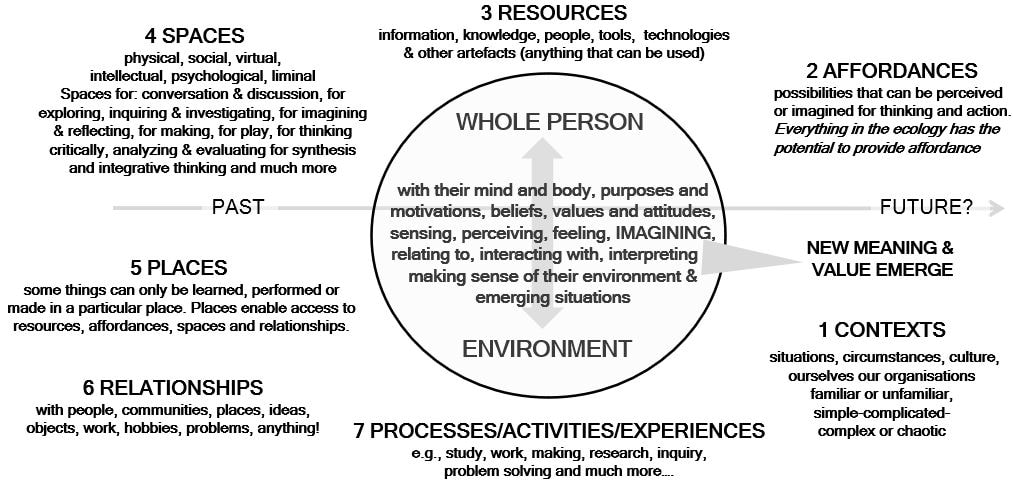

Imagining ecologies for learning and practice

The contemporary hyperconnected, contingent world in rapid formation4 demands an ecological mindset: a mindset through which we might better see (perceive and imagine) and understand the connectivity and relatedness of ourselves and the world that has meaning to us. I have argued (13, 14, 4) that we need new frameworks to help us ‘see’ (perceive, feel, reason and imagine), relate to and interact with the world in order to learn and practice. Figure 5 provides such an ecological framework. It relates a whole thinking, feeling, acting, caring person to their contexts, their needs, desires and purposes, and what they are trying to achieve in the particular situations in which they are acting and learning.

When someone encounters a new challenge or opportunity, they attempt to comprehend (see with their senses and imagination) the situation and act in appropriate and perhaps novel ways. Effectively, they create an ecology that enables them to perceive and interact with their environment in order to accomplish the things that matter to them and learning and achievement emerge from this dynamic. In this way, the person, their environment and their activities are not only connected and related – they are unified.

‘Every organism has an environment: the organism shapes its environment and environment shapes the organism. So it helps to think of an indivisible totality of “organism plus environment” - best seen as an ongoing process of growth and development.’ (16 p. 20)

“When we experience something, we act upon it, we do something with it; then we suffer or undergo the consequences. We do something to the thing and then it does something to us in return” (17 p46)

Figure 5 An ecology for learning and practice ecology (15 p86) : a framework for visualising the components, relationships and exchanges between a person and their environment in order to learn and practise. Labels (1-7) explain the key dimensions of the ecology.

A learning ecology is an ecology of practice in which the primary purpose is learning. The same framework can be used to characterise any complex practice where learning is intended to achieve something significant. An ecology for learning and practice enables the creator to put their pragmatic imagination to work in the world that has meaning to engage with situations, problems and opportunities as they emerge in their unique circumstances. Such an ecology enables the maker to ‘see’ (through their pragmatic imaginations) the affordances in their world and to act upon these affordances within their capabilities, and to extend their capabilities through their actions. Such an ecology enables the maker to connect and integrate different spaces, resources, tools, situations, relationships, activities and themselves in ways that they find meaningful, and effect various transformations (personal, material and virtual). Such an ecology enables the maker to connect and integrate their past, present and future, and connect thoughts and actions experienced in a moment and organise them into more significant meaningful experiences of thinking and action. They are the means by which the maker weaves their moments into the fabric of a meaningful life, a life they feel is worth living and a life through which they can grow and develop as a person.

The components of an ecology for learning, (summarised in Figure 5) are woven together by the maker in a part deliberate, part opportunistic, act of trying to achieve something and learn in the process. They do not stand in isolation: they can and do connect and interfere and become incorporated into other learning ecologies. An ecology for learning and practice enables the maker to think and act in an ecological (connected, relational and integrated) way, to perceive (observe, sense and comprehend the information flows), and to imagine through the creation of mental imagery what might be and what might be transformed in order to create new meanings, things and situations. And when their work is done they enable the maker to reflect on what has been experienced to make better sense of it and learn from the experience.

This article is the material and creative expression from such an ecology for learning and practice. It began with an imagined thought in the wake of an experience (my zoom meeting with the imaginED network). It was given meaning and expression as I enacted this thought on May 28th, seeing and acting upon the affordances in my life and responding to what emerged. It continued as I engaged my [pragmatic] imagination during and after living and experiencing that day in order to make deeper sense of my experience. The meaning making that is shared through this article has been co-created with all the people whose ideas and imaginations I have woven into this synthesis (my list of citations and more).

Sometimes the most ordinary situations and experiences in life can reveal important truths. Through my simple story recording some of the ways in which my imagination emerged and influenced my actions on May 28th I have tried to show how important it is to who we are – our being and our becoming. Furthermore, our cultures and everything we have made in them are the product of imagination connected to perception and reasoning, enacted in ways that give meaning and substance to our thoughts.

So when asked a question like, why should education be concerned with nurturing and developing the imaginations of learners? – the simple answer is that without their imaginations they cannot function as creative, empathic, caring and productive human beings and neither can our human civilisations. If imagination and creativity are so important to human flourishing from the level of individuals to whole societies then our educational systems need to be reconfigured to reflect this profound truth.

I have tried to show, in a variety of ways, that imagination acting in concert with perception, reasoning and the psychological spectrum of emotions (an expanded pragmatic imagination 2) is crucial to effective practice in a hyperconnected, contingent, world in continuous formation. And that we can locate imagination and the work is does in a number of credible epistemological, ontological and ecological conceptual frameworks. Our systems of education have a moral and practical obligation to help learners develop their imaginations so that they can fully participate in this fast forming and emergent world.

Furthermore, if we want learners to make a positive difference to their world, to create new value and transform it in yet to be imagined ways, we need them to use and develop their imaginations not only in the context of their academic programmes but in the multitude of contexts from which their life is formed. This supposes that our education systems will be founded up on a lifewide concept of learning, developing and achieving (18,19) and we will universally recognise the importance of the educational domain in encouraging the development and use of imagination and creativity (9) (Figure 6).

Figure 6 A model of imagination and creativity that recognises and values the educational domain(9) In this version of the model I have substituted the concept of pragmatic imagination(2) for what Kaufman and Beghetto call mini-c(9) to emphasise the reciprocal and synergistic nature of these two phenomena.

- Agnati Luigi, Guidolin Diego, Battistin Leontino, Pagnoni Giuseppe, Fuxe Kjell (2013) The Neurobiology of Imagination: Possible Role of Interaction-Dominant Dynamics and Default Mode Network Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 296, https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00296

- Pendleton-Jullian, A. and Brown, J. S.(2016) Pragmatic Imagination available at: http://www.pragmaticimagination.com/

- Jackson, N. J. (2020) Evolving Opportunities For Creative Self-Expression: New Tools For Evaluating Acts Creative Academic Magazine #16 p46 -54 available at: https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

- Jackson, N.J. (2020) From Learning Ecologies to Ecologies of Creative Practice in R. Barnett and N. J. Jackson (Eds) Ecologies for Learning and Practice: Emerging ideas, sightings and possibilities Routledge p177-192

- An idea shared by Ann Pendleton-Jullian in her zoom talk on May 28th The ideas is from Joshua Cooper Ramos’ book The Seventh Sense: Power, Fortune, and Survival in the Age of Networks Little Brown and Company Boston (2016). “The seventh sense, in short, is the ability to look at any object and see the way in which it is changed by connection.”

- Whitton, J. (2018) Fostering Imagination in Higher Education Routledge

- Ricoeur, P. (1984/85) Time and Narrative. 3 vols. trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

- Kaufman, J and Behgetto R (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity Review of General Psychology Vol. 13, No. 1, 1–12 Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228345133_Beyond _Big_and_Little_The_Four_C_Model_of_Creativity

- Jackson N.J. & Lassig, C. (2020) Exploring and Extending the 4C Model of Creativity: Recognising the value of an ed-c contextual- cultural domain Creative Academic Magazine #15 Available at:

10 Eraut, M. & Hirsh, W.(2008) Significance of Workplace Learning for Individuals, Groups & Organisations

11 Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). “Attaining self-regulation: a social cognitive perspective,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation, eds M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 13–40

12 Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think, New York: D. C. Heath

13 Jackson, N.J. (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies, Chalk Mountain LULU

14 Barnett, R. and Jackson, N.J. (eds) Ecologies of Learning and Practice: Emerging Ideas, Sightings and Possibilities Routledge

15 Jackson, N.J. (2020) Higher Education Ecosystems and the Ecologies for Learning and Practice they Encourage and Support. In R. Barnett and N.J. Jackson (eds) Ecologies of Learning and Practice: Emerging Ideas, Sightings and Possibilities Routledge

16 Ingold, T. (2000) Hunting and gathering as ways of perceiving the environment. The Perception of the Environment. Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. New York and London: Routledge, 2000

17 Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Penguin.

18 Jackson N.J, et al (Eds) Learning for a Complex World: A Lifewide Concept of Learning, Education and Development. Authorhouse

19 https://www.lifewideeducation.uk/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed