The idea of university conjures images of a large campus for thousands of students and academics providing higher education that is recognised through degrees. But Swaraj is not like this: it's more like a commune in the sense of a small closely knit community of people who share common beliefs about education and practices in learning. The idea of a learning ecosystem seems more relevant and useful to me (discussed in another post).

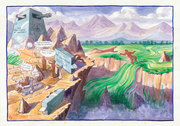

The hills surrounding Swaraj are quite barren perhaps 70% is rocky outcrop with little soil: it felt very much like the terrain I had worked in as a geologist in Saudi Arabia. It’s not easy to sustain life in this inhospitable environment but somehow the local people with their herds of goats and small areas of cultivation, managed to. Looking back from the hills the campus looks like an oasis thanks to Mr Mitra (a former Dean of Education at an Agricultural College) who came to live here 28 years ago cultivated and irrigated the land growing vegetables, bananas, dates and papaya and more.

| I was quickly welcomed into this community of 'seekers' (khojis [learners] and facilitators) and during the week I had many conversations that demonstrated their commitment to the ideals and philosophy of holistic learning and concerns for a sustainable world in tune with the needs of urban and rural Indian communities. Each day we met as a community for breakfast, lunch and dinner (an sometimes afternoon tea!) when discussions covered all sorts of topics. The group also periodically met to share progress and to review and reflect on where they were and how they were feeling about their projects. There seemed to be little distinction between khoji’s and the facilitators. | |

My own project, the reason I had come, was to learn about the context and how Swaraj encouraged learners to develop themselves as autonomous self-directing learners. My particular interest was how the pedagogical practices being used enabled khoji's to create their own ecologies for learning and achieving. Obviously I was limited to the observations I could make during the week I had chosen for my visit. During this time 7 khoji’s in the first year of the programme were part way through their second 6 week Khoji - meet. The activity they were undertaking was a self-managed project whose purpose was to interact in some way with the world outside the campus and develop a (new) perspective for themselves of the world they were interacting with. They had to decide on the output from the process and present their interaction to peers. I was not able to see these projects from start to completion but I saw enough to appreciate the learning through doing process.

Khojis and facilitators had organised themselves into five project groups.

| | Gp2: A second group of two khoji’s had decided to interact with people in the town through a stall they would set up selling artefacts that they had made, including earings made from shells and beads, wristbands and cotton bags. |

| Gp4: A fourth group chose the idea of engaging with the outer world through music. Using a range of percussion instruments. Using a range of instruments (hand drums, guitar, finger symbols and a one stringed instrument called an ectara (which means one string) and voices they experimented with spontaneous rhythms and chants and replicating existing songs. They believed that people who are not trained musically can come together and make music. They intended to perform in public after a couple of days composing and rehearsing and see what responses they received from their audiences. During rehearsals it became clear that there was a tension between the desire for creative self-expression (this sounds nice and feels good to me) and the need to consider the audience and what sorts of sounds/music they would be receptive to. One khoji in the group had given considerable thought to the project and made extensive notes. She raised many possible ideas and the negotiation that followed was to acknowledge the wealth of ideas but encourage a focus on one idea in order to achieve the goal. During the day I spent with the group there was much experimentation but no decision on what they were going to play when they interacted with people off campus. | |

| Gp5: The final group of two khoji’s wanted to interact with children. They were both interested in ‘facilitation’, One of them had recently facilitated a workshop for about 50 people at the Learning Society conference and the other shoji had several years of experience as a facilitator working with an organisation called ‘play for peace.’ They chose to work with the ‘rak pickers’, children who lived in one of the poorest areas of Udaipur who picked over the rubbish and recycled stuff that had been thrown away like plastic bottles. The two khoji’s were being helped by a former khoji/part time facilitator who had set up an informal space within the rak picker community to engage children and adolescents in interest-driven informal learning activities. | |

The reason for my visit was to try to understand how Swaraj facilitated the development of autonomous, self-directing learners in the context of their mission to develop social entrepreneurs. Clearly, I was only able to see a snapshot of a substantial programme and the fact I had picked the week of my visit meant I could only observe what was happening in that week. However, my working hypothesis is that the best way to develop learners as consciously competent creators of their own ecologies for learning and achieving is primarily through projects that they conceive, design and implement themselves. Fortunately, the type of learning processes I was able to witness was the type of process I was hoping to see.

From my field observations I was able to see that a simple brief – interact with the world outside the compound and pay attention to what you are learning through the experience, provided the catalyst for imagining, self-organising, discussion and decision making, planning and preparation and then execution of a strategy in cultural/social situations that were unfamiliar, uncertain and unpredictable. Some of the contexts being worked in were quite challenging and required a degree of courage. Perhaps also there was a level of naivety in expectations of what could be achieved, but perhaps this was also necessary as it provided a good basis for learning from the experience. The involvement of experienced facilitators or former khojis with particular knowledge and skills was instrumental in enabling khoji’s to make progress. In the short time I was there, projects were executed to varying degrees of success and some had yet to be fully implemented. Within the process facilitators encouraged participants to understand themselves and be aware of what was happening ie they were instrumental in developing conscious competence.

From khoji’s descriptions of what they had been doing I knew I could relate their thinking, doings, relationships and interactions to my framework for learning ecologies but I wanted to encourage khoji’s to recognise that learning and practice were intimately bound up in an ecology that they created/co-created.

| | The opportunity came when I was given the chance to facilitate a 90min workshop on the fourth day of my visit. I decided I would introduce the idea of learning ecologies, provide my own example (see story below) and invite participants to use the framework to reflect on their projects. Notwithstanding the difficulty of working across cultures and languages the exercise seemed to work and the four groups that were involved were all able to tell a story using the ecological framework to provide a structure to the story (stories were recorded on video). The general consensus was that there was value in the ecological framework as an aid to reflecting on and analysing a complex learning experience |

Philosophical underpinnings of the learning ecosystem

Learning ecosystems do not just inhabit a physical space or environment - they also inhabit an intellectual or philosophical space.

Swaraj has none of the features we typically associate with a university. It lacks the monolithic bureaucracy, centralized admin systems, hierarchical management, disciplinary academic structures, research, IT and other resource infrastructures. Nor does it have the QA systems and regulatory procedures. But it is an organization that is committed to helping people to learn and develop themselves. Instead it has belief and value systems and culture and educational practices that are based on a philosophy of self-governance – Swaraj. Its scale is that of a family with a culture of shared beliefs rather than a diverse complex society with competing goals, which is a university. As a family everyone knows and cares for each other. In my view Swaraj is best appreciated as a learning ecosystem devoted to promoting and supporting particular forms of self-regulated learning.

In a conversation I recorded, Rahul identified what he considered to be the key features of the community’s ecology for learning as:

- The focus on head, heart and hands. We help learners appreciate that learning through doing and experiencing what they do involves the practical, the cognitive and the emotional dimensions its not just an intellectual process.

- Learning is not just a personal matter it’s a collective matter – your decisions and acts impact on others. As they interact with the world, their families, working in communities they become more aware of their connection to a bigger self. There is a lot of peer to peer learning. We expect khojis to motivate and help each other.

- We emphasise the idea of living a healthy life with a concern for our environment and how it can be sustained. Over time khojis begin to question the value of money and what constitutes a resource. Connected to this we promote the idea of a gift ecology viewing learning as a gift and by helping others to learn and live we are giving the person a gift. Our concept for mentors is part of our gift culture. They don’t get paid - they give their time, knowledge and skills to help others learn.

- Our concept of teaching is that of facilitation in which facilitators are as much a part of the collective or social learning process ie working alongside khojis on their own learning projects, as they are helping khojis to learn and develop. The role of facilitation is not about holding the hands of khojis but of supporting and challenging when it is necessary.

To understand how these ideas and practices have come about it is important to understand the context of Swaraj, and its links to the philosophies on which it is founded. Firstly, the Swaraj approach to learning has been influenced by its parent organization Shikshantar which has been quite radical in its experiments to break away from the traditional models of education & schooling. Shikshantar has been influenced by the educational philosopher Vinoba and Rahul’s parting gift to me was a book by Marjorie Sykes ‘Thought’s on Education’, which is a translation of Vinoba’s essays published in Shikshan Vichar (1956). Vinoba, a contemporary and friend of Ghandi, was a scholar, thinker, writer and advocate for social reform. His thinking on education is linked to social reform in the wake of India’s independence. It amounted to a rejection of the British-based education system. | Shikshantar http://shikshantar.org/ a Jeevan Andolan (life movement), was founded to challenge the culture of schooling and institutions of thought-control. Today factory schooling and literacy programs are suppressing many diverse forms of human learning, intelligence and expression, as well as much needed organic processes towards just and harmonious social regeneration. Schooling is the crisis. In the spirit of Vimukt Shiksha, we are committed to creating spaces and processes where individual and comunities can together engage in dialogue to:

|

| At the heart of Vinoba’s search for Nai Talim (‘new education’) is the idea of self-reliance, self-sufficiency and self-governance which are also at the heart of the Swaraj approach to education and learning. It seems to me that education must be of such quality that it will train students in intellectual self-reliance and make them independent thinkers. If this were to become the chief aim of learning, the whole process of learning would be transformed.. a student would be taught that he is capable of going forward and acquiring knowledge himself.. it is a mistake to think that life knowledge can be had in any school. Life knowledge can only be had from life. The task of school is to awaken in its pupils the power to learn from life. (Sykes p30-31). | Vinayak Narahari "Vinoba" Bhave (1895 – 1982) was a scholar, thinker, and writer who produced numerous books. He was a translator who made Sanskrit texts accessible to the common man. He was also an orator and linguist who had an excellent command of several languages (Marathi, Gujarati, Hindi, Urdu, English, Sanskrit). Vinoba Bhave was an innovative social reformer and an advocate of nonviolence and human rights. He was arrested several times during the 1920s and 1930s and served a five-year jail sentence in the 1940s for leading non-violent resistance to British rule. The jails for Vinoba became the places of reading and writing. He wrote Ishavasyavritti and Sthitaprajna Darshan in jail, learnt four South Indian languages and gave a series of talks on Bhagavad Gita in Marathi, to his fellow prisoners. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinoba_Bhave |

Self-sufficiency, then has three meanings. The first is that one should not depend on others for one’s daily bread. The second is that one should have developed the power to acquire knowledge for oneself. The third is that a man should be able to rule himself, to control his senses and his thoughts. p31

In line with these ways of thinking Vinobe identifies a number of features of Nai Talim (‘new education’)

1 Teachers and students must regard themselves as fellow workers. ‘The major need is for the teacher and student to become work partners and this ca happen only when the distinction between the teacher and ‘teaching’ and the student and ‘learning’ can be overcome’ p62

2 Knowledge and work are both forms of the same thing and it is impossible to distinguish between a knowledge process and a work process. p62

3 NT does not discipline students it gives them complete freedom p63

4 NT is a philosophy of living its an attitude to life that we have to bring to all our work p69

5 Everyone ought to do manual labour for his food p73

All these ideas can be seen in the Swaraj learning ecosystem.

Are these educational ideas and practices relevant to UK higher education? I would say, with the exception of the 5th idea, they are. The core idea of a project-based, peer with peer collaborative learning underpinned by teacher and mentor facilitators is highly relevant to the enterprise of enabling learners to prepare themselves for a complex world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed