I took a 3 hour walk along the road I could see from my window. I walked at a slow pace so I could take in the landscape and listen to the sounds. Periodically I stopped walking and sat on a rock, closed my eyes and just listened and felt the atmosphere. I used an audio recorder to capture some of the sounds I heard. As I wandered I realised that the soundscape was as much a part of the landscape as the rocks and trees. The sounds were the manifestations of animals that were living in the landscape – insects, birds, bullocks, goats, people. It brought back memories of the time I had spent in Saudi Arabia as a geologist when I was often alone in a landscape not dissimilar to the one I was now in. Indeed, part of my experience on that walk was to interpret the rocks in the landscape as well as the way the people were using the landscape. A landscape means so much more when we can comprehend what we are seeing. The people I met were friendly given the oddness of a pale skinned foreigner walking in their landscape: it was as if it happened every day. This simple experience gave me a lot of pleasure and I decided to do the same when I got home in my own landscape. When I got back home I mixed the sound and the photos I had taken to produce a simple movie that conveys something of my experience.

My ecology for learning.

This was me interacting with my physical environment and learning from my interactions. I had a need and desire (will/motivation) to create a simple learning project to provide khoji’s with an illustration of how the concept of a learning ecology can be applied to real world learning situations. My context, embedded in the Swaraj educational process, my research into the Swaraj project-based learning process, and my longer term research into learning ecologies, (note I am a context) all provided me with purpose and fuelled my motivation.

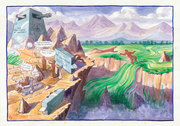

I was attracted to the scene I could see from my bedroom window. It reminded me of similar landscapes I had worked in as a geologist in western Saudi Arabia which has similar climate and topography. My past experiences were influencing my thinking in the present.

To fulfil the project brief – interacting with the outer world and forming new perspectives as a result of my interactions. I imagined a journey through the landscape paying particular attention to three things – the geology (the rocks and structures that shaped the landscape), the way people had shaped and inhabited the landscape and the sounds in the landscape (the soundscape).

My ecology embraced the wonderful physical spaces of the landscape and the intellectual and psychological spaces I created to experience being in the landscape and to pursue my inquiry. As I journeyed I formed a relationship with the landscape and the sounds in it – walking along the road, climbing the hills and sitting or standing quietly. I met some people and said hello (namestai), people reacted in a friendly and respectful way. I even asked through signs if I could take their photos and several people gave me permission, but some did not.

I made good use of my camera and recorder and their use was never far from my mind. Should I record what I am seeing or hearing? In my mind I was also relating to the idea of learning ecologies especially as I write these notes.

My process began with my walk and the pauses I made along the way to sit quietly and think about what was happening. It was peppered with photographic and audio recording and occasional note taking. After my walk I reflected on my experience, and I’m doing this again as I write up my notes. Reflection is also likely to happen when I talk about my experience and when I create my movie.

My journey of learning did not happen in a simple linear way. I have indicated that it has occurred in several episodes within the landscape, while writing, while in bed and in future when I make my movie. Through my writing and movie making I try to bring my learning into a coherent whole and present it in a way that makes sense to me and hopefully to others.

The story of the landscape

Drawing on knowledge I developed many years ago as a geologist – I can see that the landscape is formed from metamorphic rocks, softer greenish phyllites and harder white or buff coloured siliceous rocks. There are also abundant lenses and veins of quartz. From the intercalated nature of the rocks I am assuming that they were originally laid down as a sequence of muds and fine sands in an ancient sea before being compressed and folded – the rocks are steeply dipping to the north. The rocks have been eroded by water into a series of hills and valleys - dry water courses can be seen in the bottom of valleys that are presumably full during the monsoon season. One of the watercourses has been dammed – over 10m high and a small lake has been formed containing water all year round. Water is a very precious resource here.

Human impact on the landscape

People have shaped this landscape they have dammed the river, built a metalled road, dug ditches, built dry stone walls to retain soil and in the valleys create temporary ponds so the water can sink into the ground. Where there is enough soil they have cultivated the land. They build their houses and walls from the flat stones beneath their feet and there are several quarries.

In one idyllic spot where the road crossed a small valley I found a well in the valley floor, perhaps 10m deep showing me that there was groundwater at this depth. It had a pump that fed a trough for the cows. It also fed numerous pipes for irrigation and domestic purposes. A number of crops were being grown in this valley. The thought occurred to me that the agricultural practice developed at Swaraj called ‘gangamandal’ could be shared with the farmers in this valley.

| Soundscapes - sounds in the landscape Paying attention to the soundscape was an entirely new learning experience for me. While I am aware of the sounds around me and how they enrich my experience, I rarely pay attention to them for more than a few minutes. Perhaps because I am learning to record my band at the moment the idea of recording sounds appealed to me. Daytime walk I made two observations on my walk – firstly sounds sit in particular parts of the landscape but they are transient, secondly some sounds move into and through my particular soundscape eg a person riding a motorbike comes into and then moves out of the soundscape. I concluded that no sounds were permanent in a space but some sounds could be heard frequently in the same space. During my journey I walked into a number of soundscapes as people were doing particular activities. The first activity was chopping trees. The sound of chopping carried long distances. This activity was happening all over the valley and was clearly a major enterprise. It was undertaken by older women who used axes or sickals (curved cutting tools) to copice trees, while the younger women collected the cuttings, bound them into bundles and carried them on their heads. The second activity was cooking or washing. As I came near to dwellings I could hear pots and pans being used. It was close to lunch time so I guessed it was the preparation of food. Dwelling places near the road had a repertoire of sounds, children, women talking to children, goats bleating, dogs barking and sounds of domestic activity. The third activity was herding goats, mostly the goats were in one place but on occasion I saw them being herded by two girls. The fourth activity was children playing, usually around their house but also I saw and heard a small group playing on top of a hill. One of the commonest sounds on the road is made by people driving motorbikes which seems to be the main form of transportation. These are usually ridden by young men often two and sometimes three to one motorbike. You can hear the engine for many minutes before it comes into view and the same as it disappears from view. I waved to the riders as they went passed me and invariably they smiled, waved back or said hello. As well as sounds made by humans there are also sounds made by the animals who inhabit the landscape - birds, insects, goats and bullocks, all add their voices to the soundscape. Even the trees have a voice as the wind rustles their leaves. All these things bring the silent landscape to life. | Some of the sounds I recorded. Unfortunately I had no wind shields so the wind dominates some of the soundtracks - lesson for the future Walking in the windy landscape Sounds in the landscape Goats, wind, insects, cow, people Woman calling her goats Woman chopping tress and collecting wood Two men on a motorbike |

| Evening walk I did a second walk the day after in the late afternoon and evening between 4.30 and 6.30. As the sun went down. I found myself a hill about 1km from Swaraj and sat down to wait for darkness. For most of this time it was quite still and quiet. There were fewer people in the landscape and the few that were seen were on their way home. Sounds were more muted and concentrated around the dwellings scattered on the hillside. There were fewer birds singing, insects buzzing or goats bleating. The sun went down behind the highest hills and by 5.45 it was very gloomy. At this point the cicadas began to sing especially in the wadis where there was more vegetation. By the time I reached Topovan there was a cacophony of insects and possibly frog sounds. The soundscape had fundamentally changed. | Dusk soundscape Night soundscape |

The #walkingcurriculum (Gillian Judson) gets learners out of the classroom to experience the world. My walk taught me the power of a walk, punctuated by pauses, to experience, sense and make sense of the unfamiliar world on my doorstep. They changed my perception of me interacting with my environment, which was the purpose of the brief that khoji’s had been given. By taking time to experience and record some of my sensory experiences, I was able to create a deeper perspective on this particular experience of the world.

Firstly, I felt present in the landscape and when I sat, looked and listened, I felt part of the landscape. I also realised I was also part of the soundscape. As I walked on the dusty road my feet crunched the stones, my bag made a noise as it rubbed against my side and when I climbed a hill by breathing became louder and I heard stones roll away as I dislodged them with my feet. These noises interfered with what I could hear forcing me to stop frequently so I could hear the sounds that nature was making.

Secondly, I recognised my walk provided me with a rich sensual experience. I was conscious of my senses feeding in information from the environment through seeing, hearing, feeling eg the sunshine and wind on my skin and the stones crunching under my feet, smelling (eg walking past the carcass of a dead cow or a pile of dung) and tasting as I drank my water sparingly or licked the salty sweat off the top of my lip. All my senses were engaged – that is the power of a walk in which we pay attention to what our senses are telling us.

Thirdly, I felt joy. I enjoyed the physical effort of the walk and climbing hills and the way the road led me over hills to new vistas and experiences. I saw things I hadn’t seen before, like two eagles swooping over my head. I enjoyed the positive reactions of people as I said hello, and the laughing girls carrying wood who posed for me to take a photo. Because of these responses I felt that I was being accepted into the owners of this landscape, if only for a few moments.

Because of the context and the time and opportunity Swaraj has given me, I felt I had been able to taken my senses for a walk and pay attention to things they were telling me in a way that I do not normally do. In this respect it was an extra-ordinary experience. I enjoy walking at home but I thought I would try this approach of taking a camera and recorder and spending time thinking about what I was experiencing as I wandered. The experience gave me an insight into how I might facilitate an experiential workshop using these ideas.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed