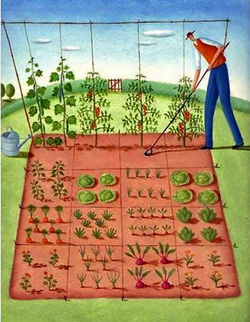

'Surely, the garden, quite apart from its tangible satisfactions, fertilizes the imagination with ample metaphors for the tilling of our interior landscape. The good life is lived best by those with gardens...... I don’t mean one must garden qua garden… I mean rather the moral equivalent of a garden — the virtual garden. I posit that life is better when you possess a sustaining practice that holds your desire, demands your attention, and requires effort; a plot of ground that gratifies the wish to labour and create — and, by so doing, to rule over an imagined world of your own.'

What a wonderful insight into the spirit of a fulfilled and meaningful life. These words provide us with the reason for why we labour over things we value in order to create an imagined world of our own. But like a real garden, the garden of our imagination, demands our constant attention, without effort it fails to achieve the potential it holds. Janna writes:

'As with the literal act of gardening, pursuing any practice seriously is a generative, hardy way to live in the world. You are in charge (as much as we can ever pretend to be — sometimes like a sea captain hugging the rail in a hurricane); you plan; you design; you labour; you struggle. And your reward is that in some seasons you create a gratifying bounty.

One must work hard to learn technique and form, and equally hard to learn how to bear the angst of creativity itself… The effort brings with it a whole herd of psychological obstacles — rather like a wooly mass of obdurate sheep settled on the road blocking your car. For you to move forward, these creatures must be outwitted, dispersed, befriended, or herded, their impeding genius somehow overcome or co-opted.

You may be unaware of how the necessary struggles of your own unconscious mind, if misunderstood, will bruise your heart, arrest your efforts prematurely, and prevent your staying absorbed in your errand. Yet, the same struggles, appreciated, will enable your creativity and the larger processes of mastery.

She considers why the mastery of creative work beckons us at all — how it extends its promise of making us “feel stimulated, warm, slightly elated, or otherwise moved; content; purposeful,” of aligning us with our innermost selves: Whether by design or by accident, many of us seem to find enduring gratification in struggling to master and then repeatedly applying some difficult skill that allows us at once to realize and express ourselves.

The work grows as our minds (conscious and unconscious) and our bodies would have it grow. Technique may require discipline and set the order of things, apprenticeships may demand periods of subordination, but the imaginative acts that propel the effort are themselves serendipitous. In your garden you may set out to clip the roses, but you notice a weed you want to pull from among the coreopsis, except that first there is a rogue branch to be snipped from the holly shrub—and on and on until dark finally settles, ending your day. An occasional task has to be done just now and just so. But mostly, you delight in meandering, allowing the work to command your attention variously — with its method inscribed by the way you encounter your plants.

Such work guards a quality of timelessness within an ever-more-time-bound world'.

These ideas helped me reflect on my own circumstance and see the things I do in a new perspective. I have found my patch of ground and search to find ideas to plant. I fertilise and nourish these ideas and labour to explore their potential. I create hybrids that connect and integrate ideas from different sources all the time trying to maintain an underlying coherence that makes my garden distinct from the gardens of my neighbours. I search for help and I'm delighted when others join me in my gardening projects. Janna Malamud Smith is right, this is the underlying pattern of my creative work.

Sources

Maria Popova Brain Pickings

Janna Malamud Smith An Absorbing Errand: How Artists and Craftsmen Make Their Way to Mastery.

Image credit Alison Jay

RSS Feed

RSS Feed