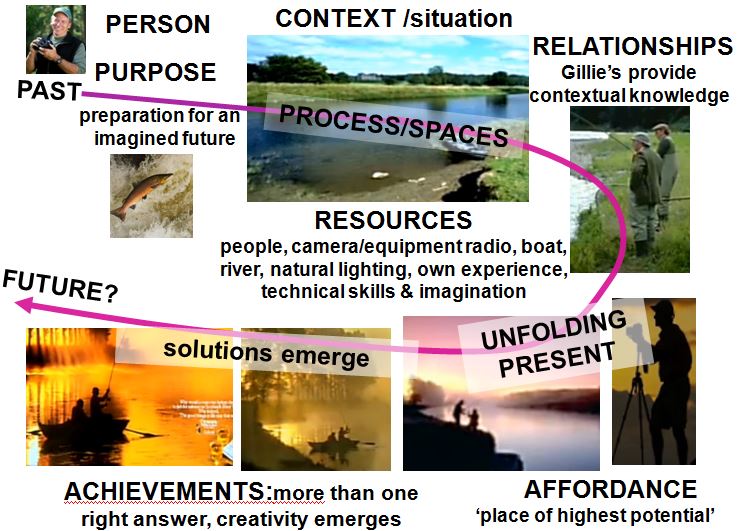

Professional photographer Dewitt Jones illustrates these principles really well explaining how, if we want to engage with nature, we much put ourselves into the space and time of highest potential. So too with our creativity projects we must put ourselves into the right time frame and mental and physical space, have access to the right tools and resources, and think and act in the space in ways that are more likely to produce the results we want, often not knowing what exactly we want until it happens, and hoping we will recognise it when we see and experience it. The second thing Dewitt Jones teaches us is there is ‘no one right answer’ but many possibilities from which we can select, but only if we keep looking and we keep searching for fresh perspectives.

|

It's the BBC's annual Get Creative Festival this week and we have invited members of the #creativeHE and Creative Academic comunities to do something creative and share what they have done in the #creativeHE forum. Just before the event I decided to make a movie of a week in the life of my garden. As the event unfolded one of the early themes to emerge was the idea that we sometimes self-impose constraints on our creativityprojects. One of the participants talked about producing a sketch every day but restricting her drawing to a 1" square. I like this idea so I adopted the idea of making and publishing a 1 minute movie everyday which I will incorporate into a story about a week in the life of my garden. Timing is important. Everything has a time and often we miss it because we are not prepared or not aware. This is certainly true where nature and light are concerned. I know, if I want to photograph or video the wild life in my garden I must be patient. I know if I want particular sorts of light such conditions are only likely at particular moments in the day, then I need to present in those moments. Professional photographer Dewitt Jones illustrates these principles really well explaining how, if we want to engage with nature, we much put ourselves into the space and time of highest potential. So too with our creativity projects we must put ourselves into the right time frame and mental and physical space, have access to the right tools and resources, and think and act in the space in ways that are more likely to produce the results we want, often not knowing what exactly we want until it happens, and hoping we will recognise it when we see and experience it. The second thing Dewitt Jones teaches us is there is ‘no one right answer’ but many possibilities from which we can select, but only if we keep looking and we keep searching for fresh perspectives.

0 Comments

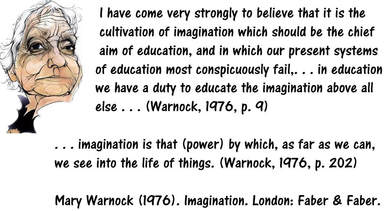

We began our first fill blown discussionon Match 8th and as I write thiis post we have been going for nearly a month on Facebook and Linked in platforms. Unfortunately only the facebook group has been active in the discussion attracting wel over 100 new subscribers during the last 4 weeks. I had recently read an article in the Journal of Creative Behaviour, which proposed a Socio-Cultural Manifesto for the purpose of advancing theory and research in the field of creativity studies (Glaveanu et al 2019). It set out a number of propositions or beliefs about creativity held by the signatories and briefly explored the implications of these for researchers in this field of study. I found the document useful to test my own views on creativity and it was gratifying to discover that my own explorations of the meaning and practice of creativity are closely aligned to the socio-cultural perspectives offered in the manifesto. Manifestos are common in the field of education. They are a public declaration of aspirations for a different and better educational future. Such documents identify and justify concerns, new needs and interests and propose changes to current practice. They provide a platform around which interested practitioners and institutions can discuss what matters and what they care about. The need for higher education to pay more attention to the growth of imagination and the creative development of learners has been recognized for many years. As we get deeper into the 21st century the future has turned out to be even more uncertain, turbulent, challenging and disruptive than we ever imagined at the start of the millennium. An education system that does not commit to the development and recognition of learners as whole, imaginative and creative beings is not enabling them to prepare themselves for a future that none of us can imagine. I felt we needed a meaty project to rebuild our community so I approached Chrissi Nerantzi and Gillian Judson to see if between us we could coordinate a discussion to develop a manifesto to Advance Imagination and Creativity in HE Learning and Educational Practice. The Manifesto, and some of the related discussions, will be published in the April issue of Creative Academic Magazine (CAM#13) during World Creativity and Innovation Week (April 15-21, 2019). This will be our collective contribution to this important annual global event. To seed the discussion I produced three papers, created a structure and identified some key questions that we needed to address. Q1 What are the most important reasons for why higher education needs to encourage and enable learners to develop and use their imaginations and creativity and invest in educational practices that encourage and facilitate such development? Q2 Is the assumption that higher education could do more to encourage and enable learners to develop and use their imaginations and creativity, correct? If it is, what is the nature of the problem relating to imagination and creativity in higher education? Q3 What does being creative mean in different disciplinary contexts? What might we mean by enabling learners to develop and use their imaginations and creativity in different higher education contexts? From an HE perspective, what are the most useful constructs? Q4 What are the important values, propositions and principles that need to underpin such a manifesto to encourage higher education to invest in educational practices that facilitate the development and recognition of learners’ imaginations and creativity? Q5 What actions might be undertaken at the level of individual practitioner, department/ subject group, institution and whole system, to realise aspirations contained in the manifesto for a more creative future? Background reading Glaveanu,V.P., Hanson, M.H., Baer, J., Barbot, B., Clapp,E.P., Hennessey, B., Kaufman, J.C., Lebuda, I., Lubart, T., Montuori, A., Ness, I.J. Plucker, J., Reiter‐Palmon, R., Sierra, Z., Simonton, D.K., Neves‐Pereira, M.S. and Sternberg, R.J. (2019) Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio‐cultural Manifesto Journal of Creative Beahviour 1-5 23 January 2019 Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jocb.395?fbclid=IwAR1OpJ2bmqneyQJECMchh7OpBHGRhg6e0ueTDZIz7mdXJHZ470xStsxpJUU Jackson, N., Oliver, M., Shaw, M., & Wisdom, J. (Eds) (2006) Developing Creativity in Higher Education: An Imaginative Curriculum. London: RoutledgeFalmer. Jackson N J (2008) Tackling the Wicked Problem of Creativity in Higher Education Surrey Centre for Excellence in Professional Training and Education Available at: We have known for sometime that Google+ is closing down in April 2019. This is the only home that #creativeHE has every known so it is quite a big emotional wrench to abandon our place of on-line conversation and interaction, not to mention the accumulation of 5 years of resources and a subscriber list of nearly 900 people. CN was the founder of the Google+ Forum and we discussed and looked at a number of alternative ‘free’ platforms but there was nothing remotely comparable. In the end we decided to set up a facebook group which we launched on Feb 3rd. I don’t like facebook very much and it might put some people off joining us but the onus is on us to make it work. So the job of rebuilding a community and a culture of participation begins all over again and in the first week we have managed to attract over 60 people. Only time will tell whether we can create a self-sustaining participatory community.

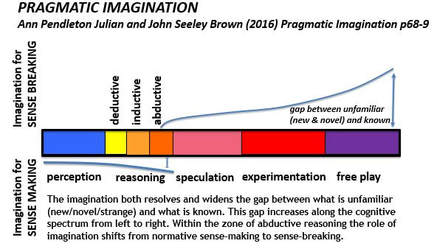

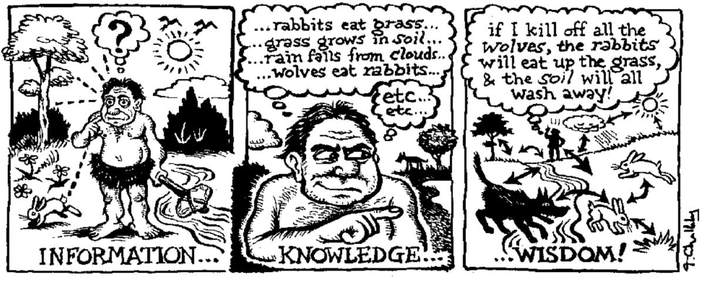

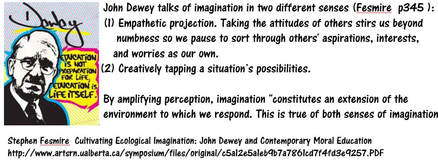

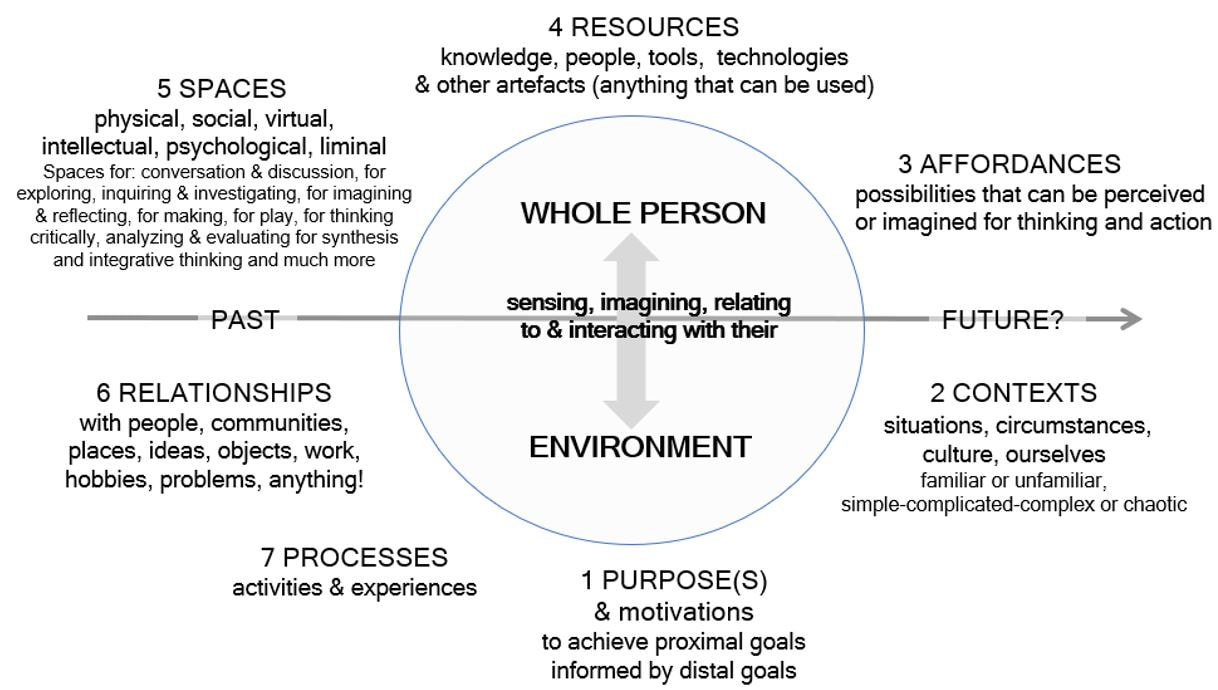

We are an inclusive community and we welcome anyone who is interested in creativity and would like to share their thoughts, feelings, experiences and practices.. https://www.facebook.com/groups/creativeHE/ I always enjoy and gain much from the #creativeHE conversations. I value greatly the opportunity to interact with, and learn from, people who care enough about the topics we discuss to generously share their time, their ideas and their lives. This conversation on Using and Cultivating Imagination (April15-21) was led by Gillian Judson supported by Jailson Lima and I was infected by their enthusism for their passion (Imaginative Education) My involvement motivated me to think about the questions being posed and the supplementary questions that always emerge. It also motivated me to engage in new inquiries which inevitably lead to new discoveries. And of course the range of perspectives and practical illustrations offered by participants encouraged me to see things in a different way to the way I normally think. Half way through the conversation we were challenged to take our imaginations for a walk (see my other blog post) and the result of this was I started a whole new blog on my garden During the conversation I was paying more attention to my imagination and how it featured in my everyday thinking: I became conscious that it emerged into my consciousness much of the time I was not deliberately thinking about something or doing something that required my cognitive attention. I have been surprised by just how active my imagination is present, it seems to be firing away most of the time but particularly when I’m by myself – like when I was chopping brambles in the garden, a physical task that seemed to provide a good space for imagining. While I was chopping I mentally visited a number of past experiences and anticipated some of the things that were going to happen in the not too distant future – a sort of mental time travel that seemed to happen spontaneously without me making it happen. In this mode my imagination entertained me, engaged me emotionally, reminded me of who I am and who I was in my past life and helped me think about what I needed to do in the near future. My own deliberate exploration of ‘Using & Cultivating Imagination’ was geared to my more general exploration of the idea of learning ecologies and ecologies of practice. Emerging from the conversation was a deeper appreciation of the way imagination relates to my evolving ideas on learning and practice ecologies we create to achieve something we value. In a learning or practice ecology, imagination is harnessed along with perception, reasoning and reflective processes for a purpose eg to learn or master something, to tackle a problem or deal with a situation, to exploit an opportunity etc.. In the March #creativeHE exploration we focused on ‘creativity in the making’, through several narratives I drew on the ideas of ‘pragmatic’, ‘representational’ and ‘generative’ imagination to try to understand how imagination was involved in particular examples of making. During the course of the conversation I came across the writings of Stephen Fesmires and his ideas on ‘ecological imagination’(1) made sense to me. This extract from Steven’s 2011 article, 'Ecological Imagination in Moral Education East and West' opens up the idea that imagination is fundamentally ecological in nature. I add my own interpretive commentary (NJ italics) and illustrations to his conceptual elaboration – which is itself a product of a disciplinary pragmatic imagination. Ecological Imagination Extract (pg 27-28) my responses in italics Like the terms space, time, and mass to the modern physicist, the terms individual and system signify to the ecologist things and the relationships that synergistically constitute them rather than ultimate existences. Conditions demand that we extend perception deeper into the socio-cultural, natural, and interpersonal relationships in which we are embedded. Ecological literacy has become essential to this. But even the most thorough knowledge about complex systems will overwhelm rather than enhance moral intelligence if that knowledge is not framed by imagination—here understood not as a faculty but as a function—in a way that relates one‘s individual biography to one‘s encompassing environment and history. NJ: I think all imagination is ecological in the sense that it relates to, and is the product of interactions with our inner and outer world eg memories, perceptions, reasonings, emotions, experiences and ‘things’ in our real and imagined world. It might be implicit but I would make more explicit the nature of encompassing environment and history (one’s encompassing past and present environment, personal history and unfolding present). I believe the function of imagination is involved in creating ecologies for learning and practice and is stimulated and put to use in a pragmatic way through an ecology for learning and practice. ….…in order to build a working definition of ecological imagination, it is essential first to better understand (or at least to stipulate) what imagination is and does…. What is imagination from a cognitive standpoint? Cognitive scientists studying the neural synaptic connections we call imagination define it helpfully as a form of ―mental simulation shaped by our embodied interactions with the social and physical world and structured by projective mental habits like metaphors, images, semantic frames, symbols, and narratives.(2) What does imagination do? More than a capacity to reproduce mental images, Dewey highlights imagination‘s active and constitutive role in cognitive life. "Only imaginative vision, he urges in Art as Experience, ― elicits the possibilities that are interwoven within the texture of the actual.(3) Only through imagination do we see actual conditions in light of what is possible, so it is fundamental to all genuine thinking—scientific, aesthetic, or moral. It is also an ordinary and integral function of human interaction, not the special province of poets or daydreamers. NJ While imagination emerges into our consciousness without any sort of attentive prompting in the everyday circumstances of our life, we can also engage our imagination consciously by creating an ecology of thinking and action that enables us to interact and deal with problem or situation. Imagination has always been an important part of my model or framework for an ecology of learning and practice(4 ) and Figure 1 but recently I have found the idea of pragmatic imagination (5) and more recently, (through Joy Whitton (6), Ricoeur’s theory of imagination (7), useful in explaining how imagination works in an ecology of learning & practice. Through a process of ecological thinking and action, [what Jullian-Pendleton and Brown call ‘pragmatic imagination’ - ‘productive [and purposeful] entanglement of imagination, reasoning [emotion] and action’(5) ] we interpret/assess the situations, decide a course of action and create (Imagine and implement an ecology of practice) the main components of which are illustrated in the model. Figure 1 An ecology for learning and practice (adapted from Jackson4) The framework or model shows key relationships and interactions between the person and their environment. The ecological framework is a heuristic to help us imagine some of the complexity involved. The labels explain an aspect of the ecology but do not say how they interact. This is revealed in the narrative of the action. The components of the ecology do not stand in isolation. They can and do connect, interfere and be incorporated into each other. In this sense imagination interacts with and modifies each and all of the components in the model.  Imagination is essential to the emergence of meaning, a necessary condition for which is to note relationships between things. To take a simple ecological example, many migratory songbirds I enjoy in summer over a cup of coffee are declining in numbers in part because trees in their winter nesting grounds in Central America are bulldozed to plant coffee plantations. Awareness of this amplifies the meaning of my cup of coffee. ―To grasp the meaning of a thing, an event, or a situation, Dewey notes, ― is to see it in its relations to other things (8) Or, as Mark Johnson recently put it, ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual or potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences.’(9) Meaning is amplified as new connections are identified and discriminated. Ideally, this amplification operates as a means to intelligent and relatively inclusive foresight of the consequences of alternative choices and policies. NJ This ideas goes to the heart of ecological thinking which I believe is best explained in terms of the idea of pragmatic imagination (4) in which perception, reasoning, imagination, [emotion] and action are all entangled in a productive way to either make sense of a situation or phenomenon or to break existing senses and create entirely new meanings.  Or as Mark Johnson recently put it, ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual or potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences.’(9) Meaning is amplified as new connections are identified and discriminated. Ideally, this amplification operates as a means to intelligent and relatively inclusive foresight of the consequences of alternative choices and policies. NJ The illustration shows this complex process of pragmatic imagination in sense making through human mind – human environment interactions. One can imagine this visualization being created in the mind of early mankind.  What is ecological imagination? Michael Pollan observes that ―proper names have a way of making visible things we don‘t easily see or simply take for granted.(10) Ecological imagination names a cognitive capacity that tends to be taken for granted by environmental and social advocates. Environmental thinkers have long recognized that ecological thinking helps us to forecast and facilitate outcomes so we can better negotiate increasingly complex systems. Yet little direct attention has been given to theorizing about the imaginative dimension of such thinking. Ecological thinking is fundamentally imaginative, at least in the sense that it requires simulations and projections shaped by metaphors, images, etc. These metaphor-steeped simulations inform choices and policies by piggybacking on our more general deliberative capacity to perceive, in light of imaginatively rehearsed possibilities for thought and action, the relationships that constitute any object on which we are focusing. By means of this general deliberative capacity, relational perceptiveness can enter into practical, aesthetic, and scientific deliberations so that we understand focal objects through connections distant in space and time. Ecological imagination is a concept too broad to encompass in an essay, but the foregoing suggests a working definition that will suffice to urge its import for moral education. Ecological imagination is here understood as relational imagination shaped by key metaphors used in (though not necessarily originating in) the ecologies. That is, imagination is specifically ―ecological when key metaphors and the like used in the ecologies organize mental simulations and projections. Our deliberations enlist ecological imagination when these imaginative structures (some of recent origin and some millennia old) shape what Dewey calls our dramatic rehearsals.  NJ So what does all this mean for education, particularly higher education teaching and learning, and for the institutions that provide opportunities for learning? A culture‘s understanding of ecosystems is an in-road for revealing how they conceive their place in a matrix of relations.Indeed, the sort of imaginative simulation used to understand an ecosystem is often relevant to our dealings with other complex systems. The horizon of ecological imagination is to a considerable degree structured by metaphors.(11) There are many conventional metaphors by which English-speakers make sense of ecosystemic relationships (e.g., web, network, community, organism, economic system, field pattern, whole, home, fabric) and trophic relations (e.g., cycles or loops, energy flows, (food) chains/links, pyramids, musical performances). Image-schematic structures such as containment, up-down, balance, and the like also play a vital role. NJ These metaphors and image schemas can be and are being used to structure the logic about learning and practice in the contemporary world. Unfortunately, higher education generally thinks in terms of linear structures and processes.. courses, with pre-deterimed and predictable outcomes. My own model of a learning ecology or ecology of practice is an example of how we might encourage the metaphorical language of ecology in learning and teaching. So my own take on using and cultivating imagination in the higher education context is, not surprisingly, connected to the affordances provided for enabling learners to understand learning as an ecological phenomenon and the pedagogical thinking and actions that empower and enable learners to create (imagine and implement) their own ecologies for learning and practice. The first step is for higher education teachers and educational developers to understand the significance in the ideas and conceptual vocabulary, the second is approach teaching and learning in with an ecological mindset. Sources 1) Steven Fesmires (2011) Ecological Imagination in Moral Education, East and West Annales Philosophici 2 (2011), pp. 20-34 2) George Lakoff, The Political Mind (New York: Viking Press, 2008), 241. For a bibliography of research on imagination in cognitive science, see Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh (New York: Basic Books, 1998). 3) Dewey, Art as Experience, LW 10:348 4) Jackson, N J (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies Chalk Mountain : Lulu 5) Pendleton Julian, A. and Brown, J. S.(2016) Pragmatic Imagination available at: http://www.pragmaticimagination.com/ 6) Whitton J (2018) Fostering Imagination in Higher Education Routledge 7) Ricoeur, P. (1984/85) Time and Narrative. 3 vols. trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 8) Dewey, How We Think, LW 8:225. 9) Mark Johnson, The Meaning of the Body (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 265. 10) Michael Pollan, In Defense of Food (New York: Penguin, 2008), 28. 11) For an analysis of the metaphorical structuring of ecological imagination, see my ―Ecological Imagination, Environmental Ethics 32 (Summer 2010):183-203

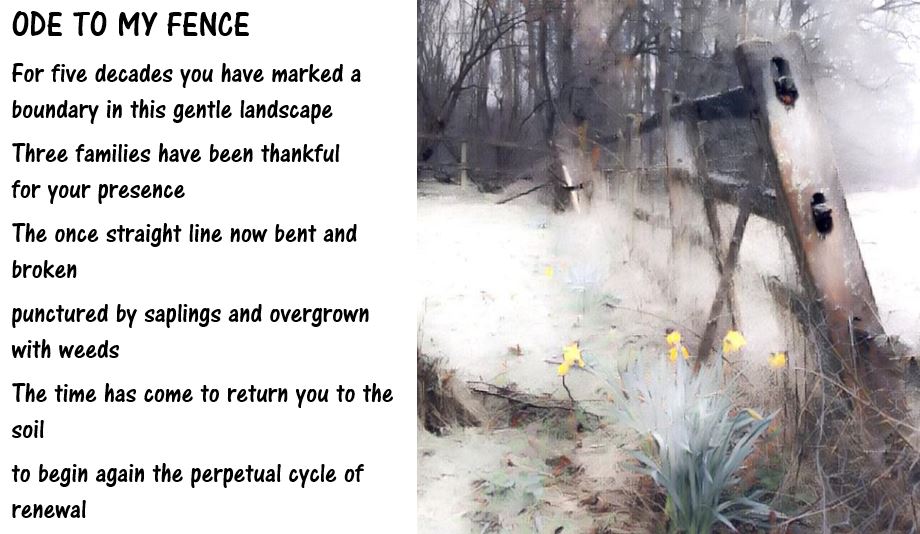

In previous #creativeHE conversations I have maintained a blog throughout the event but this time I decided to curate some of my learning at the end of the event. Increasingly I have come to see creativity as a process for connecting things that are not normally connected and giving them meanings that are significant to the creator. In this way new ideas or things are brought into existence that have value to the creator – but not necessarily anyone else. While this week's #creativeHE conversation has been unfolding, I have been writing the first draft of a chapter for a book ‘Learning as a Creative and Developmental Process in Higher Education: A Therapeutic Arts approach and its wider application’ edited by Clive Holmwood and Judie Taylor . At the same time I have started clearing part of my garden that has become seriously overgrown. Two different contexts for thinking and working brought together in time and connected in my mind through the #creativeHE conversation which always causes me to set some time aside to think about creativity and respond to the ideas and stories of other participants.

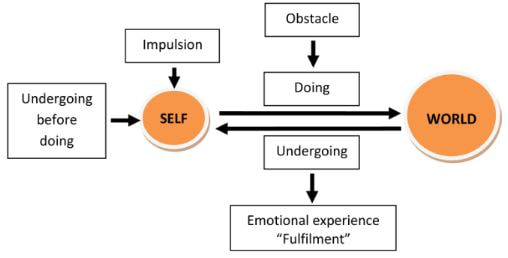

Eventually someone decides that what is considered to be rubbish has value. I thought that I could apply this rubbish theory to my gardening. For example every year I collect tons of leaves in the autumn and with much effort I drag bags to the top of the garden and dump them where they eventually decompose to create humus which I can then use to enrich the soil. I was doing the same with all the wood I was collecting, although most of it would probably be burnt as it takes so long to decompose. As I worked on my chapter I came across some ideas from John Dewey’s ‘Art as Experience’. He talks about creativity emerging through the interaction of people with their environment ‘For Dewey, what brings action and creativity together is human experience, defined precisely by the interaction between a person and their environment and intrinsically related to human activity in and with the world. Action starts with an impulsion and is directed toward fulfilment. In order for action to constitute experience though, obstacles or constraints are needed. Faced with these challenges, the person experiences emotion and gains awareness (of self, of the aim, and path of action). Most importantly, action is structured as a continuous cycle of “doing” (actions directed at the environment) and “undergoing” (taking in the reaction of the environment). Undergoing always precedes doing and, at the same time, is continued by it. It is through these interconnected processes that action can be taken forward and become a “full” experience’ (Glaveaneu et al 2013:2-3). I thought of my impulse to tackle my garden and how the impulse became sustained action as I redefined my task and begin to see the effects of my labours as new spaces emerged from beneath the entangled shrubs and weeds which fed my sense of fulfilment. I certainly experienced emotion as I encountered and overcame obstacles, often suffering from cuts as the brambles scratched me, and as I walked back to gain a bigger perspective on my modest achievement and I also felt a sense of undergoing, the sense any gardener would feel as they engaged with a task that yielded results. There is no doubt in my mind that the gardener who created my garden created a ‘work of art’ which has aesthetic value to me and everyone who experiences it. It is a constant source of pleasure for me and my family and a constant source of inspiration – I take many photographs and make sketches and paintings from time to time. I also enjoy thinking in my garden as I spend hours cutting the grass or just walking and sitting in it. There is no doubt in my mind that the gardener who created this landscape was an artist. He created a landscape from a field. So was my work in the garden in anyway artistic? I think it has potential to be but at this point in the journey I’m in a preparatory stage laying the groundwork by creating the space, developing situation specific knowledge and the motivations to do something creative. It is creative in the same way that a restorer helps to re-create a painting whose colours have faded but it is not creative in the sense of the artist creating the painting in the first place. The sense of wellbeing I felt was created from the belief that I had made a start on a job that would take several months but I had also made progress on something that was important to me. This reminded me of the research undertaken by Teresa Amabile and Stephen Kramer through which they developed their ‘progress principle’ ‘Of all the things that can boost emotions, motivation, and perceptions during a workday, the single most important is making progress in meaningful work. And the more frequently people experience that sense of progress, the more likely they are to be creatively productive in the long run. Whether they are trying to solve a major scientific mystery or simply produce a high-quality product or service, everyday progress—even a small win—can make all the difference in how they feel and perform.’ ‘The Power of Small Wins’ Teresa Amabile and Steven J. Kramer https://hbr.org/2011/05/the-power-of-small-wins The Progress Principle http://progressprinciple.com/books/single/the_progress_principle Feelings of positivity, which I’m now sure came from my work in the garden, helped me complete the first draft of the chapter I was writing. It had been a bit of a struggle at first but the discipline of writing every day for 3 or 4 hours, combined with exercising in the garden helped me complete the task.

Looking back on the #creativeHE conversation, I felt I had been able to share some of my experiences and perspectives, and I had encountered some new ideas/theories and revisited ideas I already used. I had been able to place some of these ideas into a new context (my garden project) and appreciate how they could be applied to quite a mundane task. And this consolidated my feeling that I had progressed my understandings while achieving things I cared about. What next?

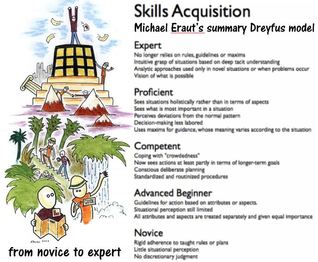

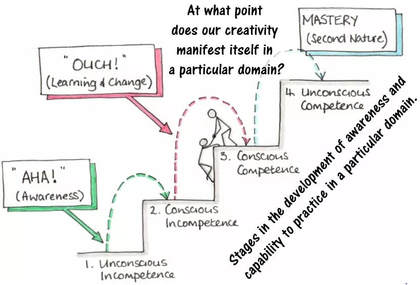

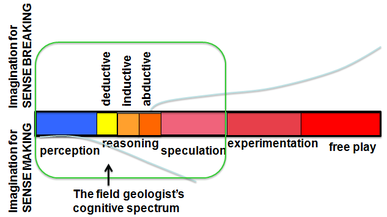

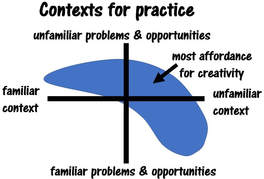

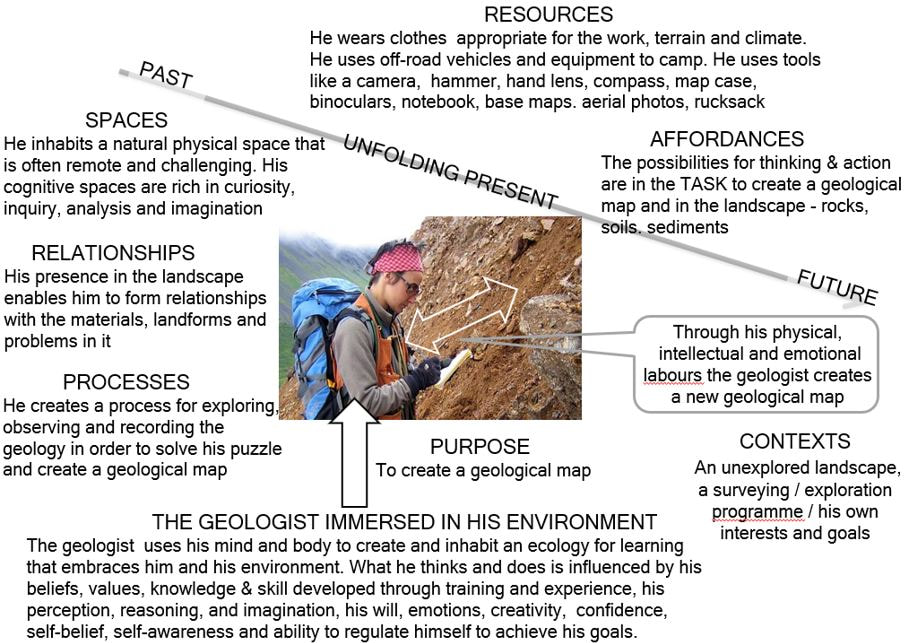

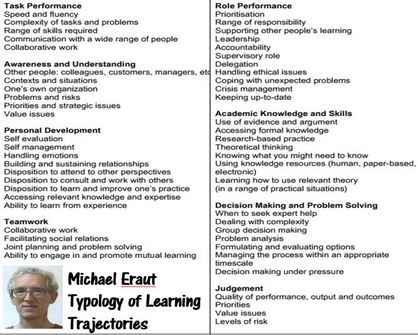

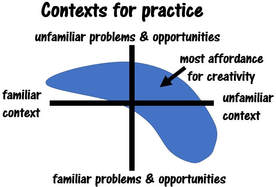

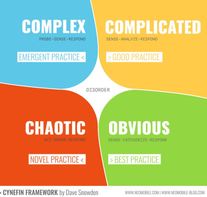

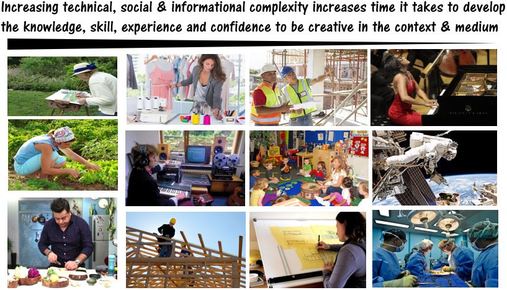

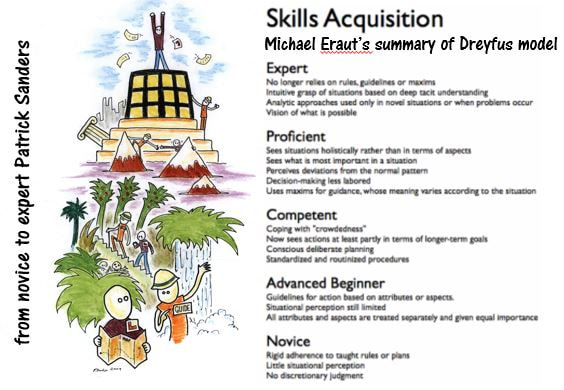

#creativeHE conversations always provide opportunities for new relationships and doing new things. In the December conversation I made friends with John Rae and since then we have been developing an idea for a future conversation on the theme of ‘Exploring Creativity through Making’ which we are going to facilitate in early March. We will invite participants to make artefacts in response to any life situation. These artefacts might be artworks, crafts, something from the digital world, or indeed anything that the maker would like to share their substance and meanings. It struck me that I had been doing this very thing quite spontaneously as the week progressed. My artefact, a pile of wood that visually appealed to me, grew out of my efforts in a natural way and I gave this the meaning of an artefact, embedded in the context and circumstances in which it was created. Sources Dewey J (1934) Art as Experience Thompson M (1979 & 2017) Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value https://www.amazon.co.uk/Rubbish-Theory-Creation-Destruction-Value/dp/0745399789 Preamble These are some of the ideas that I thought about as the #creativeHE conversation unfolded, I will keep adding to them as I reflect. I don’t think it’s easy to talk about our practice in ways that enable other people to get inside it and it’s even harder to talk about one’s own creativity. Narratives of personal experiences annotated by the individual's own interpretations and reflections seem to provide the most useful way in and we were fortunate in having a number of stories that enabled me to develop my thinking. Whenever I think about creativity in practice I make the assumption that everyone is unique, shaped by a life that only they have experienced. Therefore the way they involve themselves in a domain or field of practice, including their creative involvement, will also be unique, although their practice will be influenced by what other practitioners do in that field. I often think its much easier to demonstrate creativity when there is a tangible product arising from practice. Its one of the reasons why we associate creativity with artistic expression. Its far more difficult to demonstrate creativity when, for example, its a course of action and conversation that brings about a change or new practice in an organisation. Conversations about creativity often reflect this bias. Is creativity transferable? Well our ability to imagine and connect and combine things in novel ways, and to be resourceful can probably be applied in lots of different contexts across our lives, but we cannot suddenly jump into a domain we know nothing about and expect to perform competently and creatively.  Learning to practice in a domain During the conversation we tried to explore what happens when a person enters a domain for the first time with no domain specific knowledge or skill – at what point will they be able to draw upon their creativity? By domain, I mean a discrete area of practice replete with its own contexts, situations, cultural expectations, demands, problems and opportunities, knowledge and skill requirements, and experiences. We considered the Dreyfus model - the journey from novice to expert as we enter, learn and develop, and eventually gain some expertise in a domain. There was a sense that while this model works in some domains, where there are clearly defined stages in education and training, it was too hierarchical as a general way of explaining the development of a person to perform in a domain.  (see below) In thinking about possible alternative explanations for the development of a person to practice in a domain, I remembered the awareness / competency model (right) and thought it had good potential as a heuristic tool for understanding how a person might develop. I was working on the assumption that it is hard to be creative when you know next to nothing about the content and practice in a domain so initially we cannot be creative in a domain specific way, so the question that bothered me, was at what point could we begin to use our creativity in a domain specific way? Eventually I decided (see below) it was probably at the point we become consciously competent.  Practising to be creative Much has been written about the relationship between practice and top ‘creative’ performers in fields like music, sport and chess and Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea that "ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness." This idea has been criticized by many researchers in the field of creativity. The originator of the idea Anders Ericsson argue's the idea is more nuanced. He shows that deliberate practice can indeed help people master complex skills. Deliberate practice involves a series of techniques designed to learn efficiently and purposefully. This involves goal setting, breaking down complex tasks into chunks, developing highly complex and sophisticated representations of possible scenarios, getting out of your comfort zone, and receiving constant feedback. But according to these authors deliberate practice is most applicable to "highly developed fields" such as chess, sports, and musical performance in which the rules of the domain are well established and passed on from generation to generation. The principles of deliberate practice do not work nearly as well for professions in which there is "little or no direct competition, such as gardening and other hobbies", and "many of the jobs in today's workplace-- business manager, teacher, electrician, engineer, consultant, and so on." When my two personal tales of creativity (see earlier posts) are viewed from this perspective it is not surprising that I could create a picture that gave me a sense of joy and fulfilment in a medium I had never painted in before without any previous practice in that medium, but I was a million miles away from expressing myself creatively through the production of a mix following the recording of my band because I had not practised enough to understand how to mix a 16 track recording in a domain that requires a lot of technical know how.  Sensing affordance Being creative is a conscious and deliberate act, in order for a person to be creative in a domain they have to be able to see the affordance in situations to be able to act creatively. Perceiving is a lot more than just seeing. Jenny Willis drew my attention to the idea of ‘seeing with memory’. If we have not developed the memory from experiences in a domain how can we see in that domain? We can extend this reasoning to the full cognitive spectrum used by an experienced practitioner in any domain. When someone with domain knowledge, skill and experience (memory) tackles a challenging problem they work backwards and forwards along the cognitive spectrum perceiving (observing and comprehending informed by knowledge gained through study and experience), imagining (conceptualizing what is observed in order to create possible meanings and perhaps extending or modifying those meanings), and reasoning (the critical evaluation of what is perceived or imagined in order to evaluate possible meanings and make judgements) and reflecting on what has been seen and understood to try to develop more meaning from it. All these mental processes are harnessed in a process that involves creativity but to perceive, reason and imagine requires domain-specific knowledge and experience. I tried to give a practical illustration of this process in my account of a geologist making a geological map. The mental processes of perceiving, imagining and reasoning enable the geologist to develop hypotheses about what is being perceived and these are intermingled with the actions and activities that enable him to test his theories, to find the pieces of the geological puzzle (rock outcrops and structures), sense (observe, feel, hear, test, measure) the materials, and record (often sketching or photographing and making notes) what has been perceived. In this way ideas about the geology are tested, advanced or abandoned. For these reasons, and with this practical illustration in mind, I concluded that our ability to be creative in a domain specific way, really only begins when we reach the conscious competency level in the awareness / competency model outlined above: when a practitioner has the awareness to not only read a situation but to imagine and play with it. This does not have to apply to the whole of the domain but to areas of practice within the domain where an appropriate level of awareness and competency has been reached.  I have thought for a long time that contexts and challenges that are unknown or familiar provide the best environments for learning and creativity - we are forced to invent new practices for example. John Stephenson's matrix illustrates this. But I can now see that I need to adapt this thinking. It's clear that when a person enters a domain for the first time they are certainly challenged because they don't understand the context or the problems. They also have to learn how to practice but at this stage they do not have the knowledge or skill to be creative. Its only when they reach the conscious competence level that the challenge of new contexts and problems provides the stimulus for domain specific creativity. Paul Kleiman introduced anther variation on this theme with the idea of 'stumbling' in practices that sometimes led to the discovery of something significant - that we sometimes attribute to being creative. The idea of stumbling towards something that is not very clear and discovering things along the way is probably something we all do from time to time. But I think stumbling with a purpose, no matter how vague, denotes a level of awareness and competency, as does discovering and recognizing something as being significant. There is a great difference between stumbling with the awareness that comes from a level of knowing and understanding, and the stumbling we do when we don't really know what we are doing, as I am doing in my learning to record and mix story. I think there is something important here to the story of when our creativity becomes significant in our practices and how it emerges as we try things out and stumble across something that we are able to recognise as being meaningful and significant.  Complexity & ecologies of practice My own experiences, and those shared by participants, tell me that we can use our small-c creativity in lots of different practices across our life but we can express ourselves more quickly in some domains than others. My stories of trying to record and mix and trying to create a digital picture on the ipad illustrate this. I need to develop a lot more knowledge, skill and awareness for the former than the latter in order to use my creativity. This simple example tells us that some domains are more complex in terms of their demand for knowledge, skill and the complexity of thinking and action required to perform. This is particularly the case of professional domains like for example being a teacher or a doctor. Furthermore, admission to a professional domain might be heavily protected with strict requirements to follow a regime of education, training and certification and following entry commitments to CPD. So the journey to levels of awareness and competency where creativity can be used, is much quicker and less arduous in some domains than others. Creativity in professional practice can be simple small-c expressions but to achieve anything complex, significant and challenging – things that have not been attempted before, require imagination (vision) and a constellation of practices that have to be planned, implemented, connected and effects harnessed. This orchestration of practices over time to achieve a complex goal is best though of as an ecology of practice. John Rea described his ecology of practice beautifully and I illustrated an ecology of practice that a geologist might create to produce a geological map. When we enter a new domain we do not know how to create an ecology of practice. We are not expected to know this. What we are expected to know is how to learn in that domain and if we don’t know we will be shown or we have to find out for ourselves. We begin a process of being a practitioner and becoming a more expert practitioner in that field. Eventually, we take on our own projects and apply what we have learnt as an independent and autonomous practitioner developing our own ecology of practice within which our learning and creativity are embedded. Concepts and theories for creativity in practice Glaveneau et al (3) propose an action framework for the analysis of creative acts built on the assumption that creativity is a relational, inter-subjective phenomenon. Results point to complex models of action and inter-action specific for each domain and also to interesting patterns of similarity and differences between domains. These findings highlight the fact that creative action takes place not “inside” individual creators but “in between” actors and their environment. Human action is defined by its intentionality and the mediation of various systems of tools, signs, and artifacts that make it comprehensible and symbolic. It takes place in a setting and involves both the organism, in its unity between body and mind, and a socioculturally constructed environment. Finally, action is often joint action and is both facilitated by and facilitates human social relations (3:2) I agree with this ecological view of a whole person or persons purposefully interacting with their environment in particular ways that encourages creativity to emerge. Glaveneau et al based their action framework on John Dewey’s model of interaction (4). “Action starts, as depicted, with an impulsion and is directed toward fulfillment. In order for action to constitute experience though, obstacles or constraints are needed. Faced with these challenges, the person experiences emotion and gains awareness (of self, of the aim, and path of action). Most importantly, action is structured as a continuous cycle of “doing” (actions directed at the environment) and “undergoing” (taking in the reaction of the environment). Undergoing always precedes doing and, at the same time, is continued by it. It is through these interconnected processes that action can be taken forward and become a “full” experience “(2:2-3). Where do our impulses come from? Well the stories that were shared all give their reasons for why a particular course of action was initiated and sustained and it is very much to do with fulfilling purposes that are often bigger than yourself. You can see the elements of the Dewey model in all the stories of creativity in practice that were shared.  While creative thoughts begin in someone’s mind they are the product of their perception and imagination gained through a lifetime of interacting with the world perhaps stimulated by particular interactions and circumstances in the present. These ideas are reshaped as they are brought into material existence through further interactions with the world. Considering the narratives of creativity that were volunteered during the discussion the definition of personal creativity proposed by Carl Rogers (5) would fit this action framework and my working concept of ecologies of practice namely, ‘the emergence in action of a novel relational product growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, or circumstances of their life’. In my narrative (6) of a field geologist using his practice to create a geological map - a creative artefact in the domain of geology I tried to demonstrate how the production of the artefact emerges through his ecology of practice as he interacts in a purposeful manner with the environment in which he works. Sources 1 Gladwell M (2008) Outliers: The Story of Success Penguine 2 Ericson A and Pool R (2016) Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise Hardcover Eamon Dolan/ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 3 Glaveanu, Todd Lubart, Nathalie Bonnardel, Marion Botella, Pierre-Marc de Biaisi, Myriam Desainte-Catherine, Asta Georgsdottir, Katell Guillou, Gyorgy Kurtag, Christophe Mouchiroud, Martin Storme, Alicja Wojtczuk and Franck Zenasni (2013) Creativity as action: findings from five creative domains (2013) Frontiers of Psychology v4 1-14 4 Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Penguin. 5 Rogers, C.R., (1960) On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin 6 Jackson N J (2017) An Ecology of Practice - Making a Geological Map (copy below)

VERSION 1 published 09/12/17 revised 10/12/17

DAY 3 Creativity in practice - what can we learn from people who are very good at what they do?6/12/2017 We can learn a lot about creativity in practice and creativity as practice from people who have developed significant expertise in their field. Having recently watched interviews and storytelling by Dewitt Jones, David Hockney and Hans Zimmer what they all seem to have in common is great skill, modesty, a significant work ethic, enthusiasm for and deep interest in what they do, and critically a wonderful sense of awareness gained from years of tuning in to what matters. Furthermore, they all appreciate the story in what they see and how their work evolves through their interactions with the world. What can Dewitt Jones (photographer) teach us about his creativity in practice? In this video clip professional photographer Dewitt Jones talks about an experience he had taking photographs for an advert he made in Scotland. His narrative reveals what he thought and how he felt as he was faced with the reality of the situation and his explanations of what happened reveal the way he interacted with his environment. Through his story we can appreciate how his thinking, emotions and practice combine in ways to enable him to create new and original artefacts. What can we learn from this story about creativity in/as practice? Do you have a story that illustrates how your creativity enabled you to gain something valuable from a situation? Several participants made some interesting and insightful observations about DJ's story. Gillian Judson A few things to contribute today! First, what resonates with me is that connection between learning more about the river and his imagination being engaged...he keeps repeating "now I'm getting intrigued" (at first he was unable to see the extraordinary in this "ordinary" and somewhat (at first) disappointing location. He needed those experts (I would call "story-tellers") to show him what was unfamiliar (Who wears ties for fishing?), extreme, unique and ultimately wonder-full. I also notice he juxtaposes the "intellect" and "intuition"--"turn around Dewitt". He was seeking what he called "the place of most potential" and "the right answer" (ultimately he found many and he surprised himself over and over again. Knowledge. Heart. Wonder. "Attention") he said he was "paying attention"--a full-body attention as far as I can tell. An attention fuelled by what seemed to be a quest for some kind of "magical" result. "By being creative, we really do fall in love with the world." Mar Kri some quick thoughts on this : some of the things I hear in his story ... "I done my homework I had images on my head..."..i understand from this that pure intellect isn't sufficient to get us in that space.. that DJ did more than engaging his intellect or formulating a pre planned/pre thought plan on "how to do it". he shows how entering that space required from him an attitude of letting go of his "intellect", and making allowance to different forms of knowledge - or rather knowing to emerge- , eg: he was willing to enter a space of not knowing... this i think is hugely important when we play with the idea of creativity This particular bit in his story reminds me of an article i read recently that reaching a space of disequilibrium is significant in order to reach a sense of equilibrium and meaning all over again...a very important factor towards him reaching this creative space was his willingness and determination to go there on his own..."to the place of most potential"; this communicates too a trust in this unknown process? Also for me what comes out very distinctly is the relationship between man and nature and the space it creates affords for our engagement and birth of creativity... "my intuition s screaming to me"....if our intuition has a voice , a story to say ,then its imperative we begin to listen more closely and expose these stories, in our attempt to "get back in that space".. Paula Nottingham A humbling story really, seeing the process rather than the act of creativity. I realised thinking of the story that limited circumstances for the creative happening abound because many things are pre-planned. Perhaps the key is building in elements that are not planned. These comments triggered a number of thoughts. Firstly, DJ is a masterful story teller and I guess he looks for story in what he is perceiving. Perhaps story is a way of discovering, representing and communicating meaning. I liked the way GJ connected learning and imagining and it seems to me they combine in a synergistic way to motivate him. His enthusiasm grows as he learns and uses his imagination to see more potential in the situation to achieve his goal and he then has deeper insights into what will be the sites of greatest potential in his unfolding story. 'Intriguing' is a a good word to describe this state of being sucked in to another level of awareness and his story is all about self-awareness and having his whole sensory system engaged with the unfolding situation. The images he finally produces fit well your notion of a quest for something magical. I was looking at an interview with David Hockney and he said something very interesting in the context of art school education. "You can teach the craft its the poetry you can't teach". Perhaps what we witness with DJ is him using his craft to search for the poetry in this situation. I think MK & PN are right to highlight that this story is all about working with uncertainty and an unfolding and unpredictable situation requiring a mode of being that is open to the feedback being received and sensed from the environment. These are conditions that are often the opposite to what we try to create in the higher education environment so it is little wonder that learners are not prepared for such situations. How can they develop intuition for situations and circumstances they never or rarely encounter in their disciplinary studies? My own contribution to understanding his practice is to try to relate it to the idea of an ecology of practice. DEWITT JONES' ECOLOGY OF PRACTICE

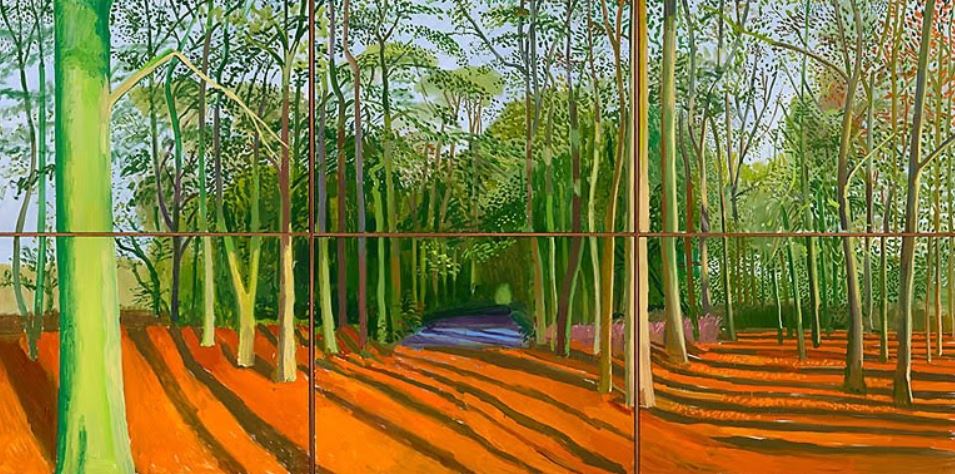

What can David Hockney (artist) teach us about his creativity in practice?

Here is a man with great artistic talent, intelligence and a work ethic that few of us can match who never stops thinking about his work, who sees the extraordinary in the ordinary, who is a craftsman who makes poetry with his images. His observations and narrative illuminate his practices. They reveal his journey and how his past experiences and what he values are brought to bear in his present work "The Yorkshire landscape is painted by someone who has lived in LA for 30 years". He reveals how he feeds off the environment in which he places himself "I am affected by the space.. it thrills me". His mind is shaped by his environment and he in turn represents his environment is ways that have never been seen before. The Hockney film was not something that was planned or designed into the conversation. It's included here because I found it while the #creativeHE conversation was unfolding and it was relevant to my experience and my practice. During the course of the conversation I discovered that one of our moderators Jenny Willis wasn't well. I encouraged her to watch the DH film and the next day she made a post to share her reactions and experiences. Jennifer Willis The art of seeing Apologies for not joining the conversation sooner – having been coughed over by countless poorly children for the last week or two, I have inevitably succumbed to the same virus. Nevertheless, Norman has coaxed me into action with his suggestion that I view David Hockney’s wonderful video, The art of seeing. My preferred artistry is through words and thoughts. As I watched the video, I was bombarded with inspirational ideas and memories. Just this weekend, I was driving back to London from my aged father’s home in the Cotswolds. It happened to be one of the nights when the harvest moon dominated a clear sky. Driving directly towards the gigantic orb was mystical: trees were silhouetted as I chased its ascending path. Surely this was an example of my seeing ‘with eye, hand (in my case, mind) and heart’? Earlier in the day, we had visited an antique shop where we purchased a large glass kilner jar filled with mesmerising shells. My husband wanted the jar, I the contents. Hockney also says ‘We always see with memory’. Was my attraction to the shells a regression to the four year old me who collected shells on the banks of Lake Habbinya, lovingly filled a plimsol bag with them, only to have to leave these treasures behind when we were evacuated back to England at the outbreak of the Suez crisis? Whatever the reason, taking out each shell this week, touching its surface, admiring its natural formation, colour and smell has brought me many hours of pleasure and revitalised my need to create. The sense of loss and joy was another theme I played with as I watched the video. Throughout, it was clear that Hockney has been strongly influenced by China. There was an unspoken reminder of the Zen paradox: we need, for instance, to have experienced pain to truly appreciate pleasure. And perhaps this brings us back to the stage of learning: with age and practice, we become the skilled expert, but that does not necessarily mean we retain the keen emotional component of art. As Hockney observes, ‘You can teach the craft, it’s the poetry you can’t teach.’ He has succeeded in retaining the poetry, whilst being an expert, yet also having that essential quality of curiosity and adventure. He is not afraid to move into unexplored media and return to being a novice. He does this by knowing how to see. It is this ability to remain young in spirit that keeps him (and the rest of us who defy our chronological age) sensitive to the beauty of nature and immersed in life. I thought Jenny had provided a great example of finding meaning in the film that is deeply personal and linked her insights in a memorable and creative way to her own life experiences. I think I will always now remember 'seeing with memory', which I hadn't paid attention to before.. but my goodness how true it is that our perceptions of the world are always constructed through memory. Inspired to 'paint' I enjoyed watching Hockney paint in his field environment. It gave me a sense of how he immerses himself in the landscape he is painting and how he sees and feels and then makes his mark using his tools and his medium. I was intrigued and I kept searching YouTube for more clips of him painting. I was infected by his quiet enthusiasm for digital painting on the ipad - he made it look easy, which I guess is the mark of a good teacher - someone who eases the challenge of learning. I thought I'd like to try and paint something and I looked up how he used his ipad to paint. Then I found a lovely clip by Jeannie Mellersh who showed me that one of the ways we can understand someone's practice is to try and emulate their practice. In the video clip she explains and demonstrates how she used her ipad to paint his April 28th picture. "I've been looking at David Hockney's exhibition in London showing his I ipad paintings I've recently bought an ipad in order to understand how he painted one say this one on April the 28th [Angie is looking at the catalogue] I have attempted to recreate it on my iPad" This practical down to earth demonstration really helped me understand her practice and david's practice as an ipad painting craft.

I was so inspired by Jeanie's demonstration that I borrowed my wife's ipad, downloaded a paint app and had a go for myself. Its a finger digital painting of my garden and I enjoyed making it so much that I am going to invest in some digital brushes. On a small scale this is an example of being inspired to do something I'd never done before and it came from two people sharing their practice. The advanced practitioner shared his passion and revealed the beauty in the landscapes I sometimes take for granted. The competent practitioner showed me how simple it was to learn the techniques and that gave me the confidence and will to try for myself. The result was satisfying and it felt creative to me (but not necessarily anyone else although my wife felt it was). I can now see the potential in the medium for doing more. I am not a complete beginner, I have drawn and painted off and on throughout my life but not in the last 18 years. I guess this proves to me that, in some areas of practice, we can be creative and productive with relatively little knowledge and skill. What can Hans Zimmer (musician/composer) teach us about his creativity in his practice? Here are a bunch of short video clips of Hans Zimmer the famous film composer talking about his practices and showing where he practices. You don’t have to listen to them all (unless you want to). The invitation is to dip into some of them and identify something he is saying that resonates with you and your practice and explain the connection. Hans Zimmer - influences and backgrounds Importance of mentorship. Seeing how other people solve problems.. You have to put your hours in.. great believer in 10,000 hrs to get good at something Hans Zimmer Making of Intersteller Reveals a process but not the details of practice.. appreciate a set of relationships..and interactions between people (director, musicians, family) story… stuff emerging in action Hans Zimmer & Christopher Nolan The Making of Dark Knight The conversation and interactions between Director and Composer. The Director pushing.. Huge amount of experimentation.. 9000 bars… ‘joker is there but you have to find it’ Hans Zimmer in his studio Part1 Works in a very particular space, tools, books lighting, and surrounded by other musicians able to have a conversation with other musicians Hans Zimmer in his studio Part 2 I don’t have confidence. I have no idea how to so this I’m not good enough to do this .. it happens on everyone.. Hans Zimmer in his studio Part 3 Every movie I work on I try to have a concept … I do try to figure out some new ideas and a new tone and a new style…

I felt positive about the way the conversation had unfolded and what I had learnt in spite of the small number of participants, and hoped on day 2 that more personal stories would be shared as we focused on the environment in which we conduct our practices.

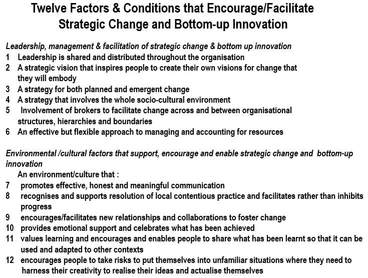

Drawing on your own practice experiences in any aspect of your life, how does the physical, social, cultural, organisational, virtual, intellectual and psychological environment we inhabit, influence our practices and our creativity in our practices? As a stimulus I used what I can now see as an enchanting exploration of Japanese culture by Dr James Fox (BBC TV). http://www.creativeacademic.uk/creativehe.html The programme (one of three) provided me with a great illustration of the way in which an artefact can enchant me and I hope other participants. Russ Law was first to respond by painting a dismal picture of the educational environment he witnesses through his professional, personal and voluntary practices. “I'm exercised by the contradictory pressures and requirements imposed by successive secretaries of state for education, especially around the curriculum. Schools are held to account, supposedly, for providing a broad, balanced and creative curriculum, while at the same time creativity is obstructed by the time spent by teachers and learners on highly prescriptive and narrow criteria (on which they will be judged), that require teachers to play safe and use every available minute for the core curriculum that is formally assessed. We have token amounts of time allowed for the arts, but these aren't valued enough. The only real creativity we see is that used by teachers to survive the time-consuming bureaucratic demands and relentless pressures they endure.” From my own interactions with teachers in higher education I know that if you invite a group of educational practitioners to talk about what inhibits their creativity some reference will be made to the bureaucratic and regulatory environment, and the culture of risk avoidance that characterizes university environments. So if this is an important constraining factor in the environment, how do so many practitioners overcome or get round this constraint to practice in ways that enable them to use their creativity to encourage students to learn in creative ways? But this is the tip of an iceberg. A few years ago I made a study of how the factors and circumstances that enabled and facilitated a group of higher education practitioners to innovate. After interviewing over 20 people who had been involved in the innovation project I constructed a questionnaire and then invited them to complete it. I was shocked at the number of factors and conditions in the work environment influenced them and their practices as they tried to innovate. It shows just how complex the idea of environment is to an educational practitioner who is trying to be creative to change their practice.

A story of making practice

Teryl Cartwright provided a really engaging story about the way her practice and creativity was affected by her environment in the context of her pottery class. The video clip she attached helped bring her written description of the environment to life. I’ve been taking a pottery class this past month and it has been a joy to enter into such a creative space. When you drive to Shiloh Pottery, you go past small towns and farms and then up the driveway past the chicken house of noisy residents to what looks like a log cabin. The door handle is actually a wooden latch you pull up. You walk into a room of the finished pottery and are greeted by a golden retriever named Bear. The grey and white cat is named Dog. He has another name now but I prefer that one. As you walk into the workspace, the instructor Ken greets you. He’s like Santa with a gruff and whimsical sense of humor and long-standing patience. He sometimes carries a pen in his beard. There are always others there, students or helpers, working or visiting, or as Ken calls it, “playing in the mud.” To the left of where I usually sit at the wheel is a huge aquarium with two turtles the size of dinner plates. The spigot where I fill the bowl of water is a dragon fountain, spewing hot water instead of fire. The tools which I borrow are along the wall near the chemicals which make the glazes. The mixed glazes are kept in the huge garbage cans with towels thrown on top. The de-aired clay is on a shelf by the work my daughter and I did the previous week as we learn to throw our pots. We cut the clay with wire and weigh it before patting it into balls. If you get air in the clay you knead it out on the table as if you are making bread with a vengeance. The plate which holds the clay on the wheel is called a bat and the ball of clay is to be slapped to its center after I wet the bat slightly to make the clay stick. If you do that slap right, the thunk does sound like making a hit in baseball. When the wheel spins and I must center the clay, I’ve been learning how to keep my hands still. It seems like the most counter creative thing you learn. Usually, you think you have to be moving to be creative but while the wheel spins and you center the clay, your hands learn not to fight the clay as much as hold still and surround it. The clay is like a wild animal that needs firmly but caringly trained, much like creativity. Your knees have to be pressed on either side of the wheel and your elbows sit on your knees, twice the power of The Thinker. After the clay has been centered which is the most important thing (even in creativity centering is everything!), you press into the center with your thumbs to make a space and you use a pin tool to see how thick the bottom of your pot is. Finally when you get that depth right you overlap your thumbs, making them into a “W” and you use your middle fingers on the inside and outside of the clay to form the sides as evenly as possible by moving them up together at a uniform speed at the three o’clock position with the other fingers alongside them for guidance. You can bring more clay up from the bottom based on your pressure of your fingers but you have to gradually let go as you get to the top or the clay will form lopsided edges or worse, break. You can’t keep going over and over the edges either, Ken calls that “loving it to death” and it doesn’t fix your mistakes, it often creates new ones. I think one of the most unrated parts of the creative space though is not the sights but the sounds. It’s been interesting how differently my pots come out and I know some of this is influenced by the variety of music in the background often from the 60s and 70s. Then there are the sounds of the wheel as I press the pedal at different speeds like I’m driving. There are the muted conversations, the voice of the instructor, the blending of the glaze in the trash cans with a power tool that sounds exactly like a kitchen mixer, the water from the dragon, and the thunk of the clay ball hitting the bat, all these little things inspiring me to create pottery. I sometimes close my eyes as I’m centering the clay and centering myself to listen to being creative and to hear myself being in a creative space. I don’t know what sounds creative to you, but it has been fun to find out here in this new creative space in my life that sounds so different than the small thunkings of a writer typing on a laptop.Teryl CartwrightA2: Thank you +Teryl Cartwright I really enjoyed reading this - and the evocation of th

I thought this was a wonderfully emotionally engaging story which engaged really well with the question of how our environment influences our practice and creativity and also yesterday's question about when are we able to use our creativity in the process of developing entirely new practice. The description provided a sense of embodiment as she grappled with the physical materials, the technology and the space drawing on all of her senses. It seemed like an authentic account of a personal ecology of practice that had been lived and experienced. The same thoughts prompted Sandra Sinfield to comment "I would like our HE classrooms to be more like primary school (where people can stay in and decorate and own a space) - rather than secondary ones (where people are nomadic moving from room to room - propelled by the bell). Or to use a more university descriptor - I wish we could all have more of a Studio style space - so that the room itself started to denote and connote the sort of activities that take place there and the modalities both adopted and inhabited. So that work is displayed - and can be taken up again - and that the very air and light and sounds create that 'making' atmosphere.

Another maker story