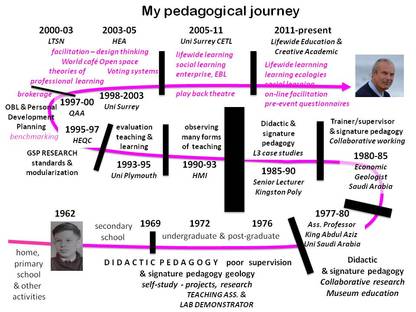

I have surprised myself in this conversation by focusing on that part of my career when I trained and then practised as a geologist (25 years). Being a geologist involves quite a lot of physical effort so perhaps it this made it easier for me to visualise how a body might be involved in a creative process in a disciplinary context.

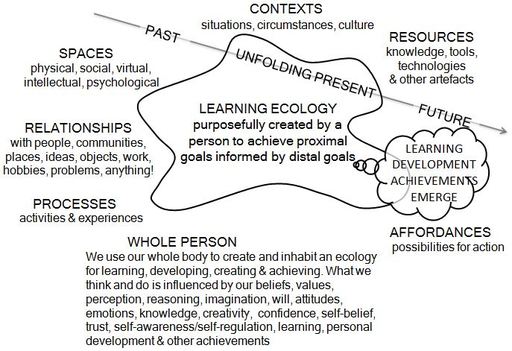

In this post I want to explore the idea that our body does not just inhabit a physical environment, rather when trying to learn and achieve something, we create what I call a learning ecology. The idea of ecology encourages us to think more holistically and more dynamically about the way we inhabit and relate to the world. Applying the idea of ecology to learning, personal development and achievement is an attempt to view a person their purposes, ambitions, goals, interests, needs and circumstances, and the social and physical relationships with the totality of the world they inhabit, as inseparable and interdependent. Figure 1 shows the important components of a learning ecology.

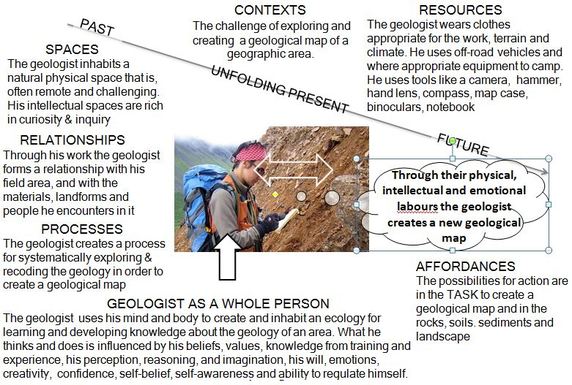

Figure 1 Important components of a learning ecology (Jackson 2016) shown in relation to the work and functioning of a geologist

Geologists are 'knowledge workers' in the sense that their role involves developing particular sorts of knowledge to understand the geology of a particular area, for particular purposes - for example to explore for useful rock or mineral materials. This knowledge cannot be developed without physically going into the field (the environment), walking over the ground, observing, recording and making sense of what is encountered. Because they are knowledge workers they develop a foundation of theoretical and practical knowledge and skills relating to the use of such knowledge before they begin to practice.

A geologist will be employed to develop knowledge and understanding about the geology of particular areas. Creating geological maps to show what rocks, structures and mineral resources exist is something that all countries must do to create their own mineral resources inventory. You cannot build or create infrastructures and industries which exploit the resources of the natural environment without this knowledge.

A geologist might be given the task of creating a geological map where none exists or creating more detailed maps where they do exist. In order to achieve this they will create an ecology for learning. Prior to going into the field a geologist will gather existing information about an area they are intending to map, acquire base maps if they exist or use aerial or satellite photographs if none exist. These are resources and tools that the geologist uses to record observations about what is found and enable such information to eventually be turned into a map. They will develop a strategy for tackling the problem and plan logistics like how and where they will live in the field, how much food and water they will need, how they will get there and move around, how they will communicate etc..

The thought processes of a geologist (any natural scientist) move along the cognitive spectrum of perception (observation informed by lots of knowledge gained through study and experience), imagination (conceptualisation of what is observed) and reasoning (the critical evaluation of what is observed). We might also throw in reflection on what has been understood to try to make more sense of it.

The body has to work hard to perceive - physically the geologist has to get into the field to see the rocks he is interested in, to see and measure the structures and the relationships between different types of rocks, to take samples for further analysis, and to record these things on a map.

Being a geologist involves quite a lot of physical labour and performing particular routinised actions - like locating their positions on a map or aerial photograph made easier with GPS navigational aids, measuring the dip and strike of bedding in rocks, breaking rocks and examining fresh surfaces with a hand lens, photographing and sketching rock outcrops and annotating sketches with observations, and where there is little outcrop examining the soils.

This observational process is integrated with imagination - the geologist tries to solve a 3 dimensional puzzle with only bits of information and lots of gaps. He tries to understand the relationships between one type of rock and another and develop understanding of the geological history of the area. So conceptualisation - the building of working hypotheses to explain the geology goes hand in hand with the perceptual-observational process. And as a hypothesis forms the body is involved in testing it. A geologists mind has to enable him to go as he engages systematically with his problem. His body gets his senses and his mind to the places he needs to be in order to find the evidence that confirms his hypothesis or not. Past experience has shown me that there is much intuition involved in this process. Sometimes it just feels right to do something.

The geologist's observations and recording enable him to relate and synthesise disparate pieces of information to create a bigger picture. And after the day, back at camp, there is the pondering and reflection on what has been seen as the day's observations in notebooks are revisited and plotted on the base map. These analytical and conceptual processes continue after the field as samples are analysed and understood better. These elements of cognition, doing and being work together in a merry dance and the knowledge and understanding that is created, together with new artefacts through which this knowledge is communicated (maps and reports) is the creative outcome of this process.

This is my example of how body and mind work together to producse a creative outcome in one disciplinary context. So the question is can the same approach be used in other disciplines?

Source of learning ecology idea

Jackson (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies https://www.lulu.com/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed