I always enjoy and gain much from the #creativeHE conversations. I value greatly the opportunity to interact with, and learn from, people who care enough about the topics we discuss to generously share their time, their ideas and their lives. This conversation on Using and Cultivating Imagination (April15-21) was led by Gillian Judson supported by Jailson Lima and I was infected by their enthusism for their passion (Imaginative Education)

My involvement motivated me to think about the questions being posed and the supplementary questions that always emerge. It also motivated me to engage in new inquiries which inevitably lead to new discoveries. And of course the range of perspectives and practical illustrations offered by participants encouraged me to see things in a different way to the way I normally think. Half way through the conversation we were challenged to take our imaginations for a walk (see my other blog post) and the result of this was I started a whole new blog on my garden

During the conversation I was paying more attention to my imagination and how it featured in my everyday thinking: I became conscious that it emerged into my consciousness much of the time I was not deliberately thinking about something or doing something that required my cognitive attention. I have been surprised by just how active my imagination is present, it seems to be firing away most of the time but particularly when I’m by myself – like when I was chopping brambles in the garden, a physical task that seemed to provide a good space for imagining. While I was chopping I mentally visited a number of past experiences and anticipated some of the things that were going to happen in the not too distant future – a sort of mental time travel that seemed to happen spontaneously without me making it happen. In this mode my imagination entertained me, engaged me emotionally, reminded me of who I am and who I was in my past life and helped me think about what I needed to do in the near future.

My own deliberate exploration of ‘Using & Cultivating Imagination’ was geared to my more general exploration of the idea of learning ecologies and ecologies of practice. Emerging from the conversation was a deeper appreciation of the way imagination relates to my evolving ideas on learning and practice ecologies we create to achieve something we value. In a learning or practice ecology, imagination is harnessed along with perception, reasoning and reflective processes for a purpose eg to learn or master something, to tackle a problem or deal with a situation, to exploit an opportunity etc.. In the March #creativeHE exploration we focused on ‘creativity in the making’, through several narratives I drew on the ideas of ‘pragmatic’, ‘representational’ and ‘generative’ imagination to try to understand how imagination was involved in particular examples of making.

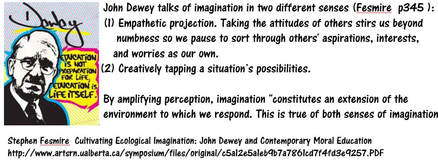

During the course of the conversation I came across the writings of Stephen Fesmires and his ideas on ‘ecological imagination’(1) made sense to me. This extract from Steven’s 2011 article, 'Ecological Imagination in Moral Education East and West' opens up the idea that imagination is fundamentally ecological in nature. I add my own interpretive commentary (NJ italics) and illustrations to his conceptual elaboration – which is itself a product of a disciplinary pragmatic imagination.

Ecological Imagination Extract (pg 27-28) my responses in italics

Like the terms space, time, and mass to the modern physicist, the terms individual and system signify to the ecologist things and the relationships that synergistically constitute them rather than ultimate existences. Conditions demand that we extend perception deeper into the socio-cultural, natural, and interpersonal relationships in which we are embedded.

Ecological literacy has become essential to this. But even the most thorough knowledge about complex systems will overwhelm rather than enhance moral intelligence if that knowledge is not framed by imagination—here understood not as a faculty but as a function—in a way that relates one‘s individual biography to one‘s encompassing environment and history.

NJ: I think all imagination is ecological in the sense that it relates to, and is the product of interactions with our inner and outer world eg memories, perceptions, reasonings, emotions, experiences and ‘things’ in our real and imagined world.

It might be implicit but I would make more explicit the nature of encompassing environment and history (one’s encompassing past and present environment, personal history and unfolding present). I believe the function of imagination is involved in creating ecologies for learning and practice and is stimulated and put to use in a pragmatic way through an ecology for learning and practice.

….…in order to build a working definition of ecological imagination, it is essential first to better understand (or at least to stipulate) what imagination is and does…. What is imagination from a cognitive standpoint? Cognitive scientists studying the

neural synaptic connections we call imagination define it helpfully as a form of ―mental simulation shaped by our embodied interactions with the social and physical world and structured by projective mental habits like metaphors, images, semantic frames, symbols, and narratives.(2)

What does imagination do? More than a capacity to reproduce mental images, Dewey highlights imagination‘s active and constitutive role in cognitive life. "Only imaginative vision, he urges in Art as Experience, ― elicits the possibilities that are interwoven within the texture of the actual.(3) Only through imagination do we see actual conditions in light of what is possible, so it is fundamental to all genuine thinking—scientific, aesthetic, or moral. It is also an ordinary and integral function of human interaction, not the special province of poets or daydreamers.

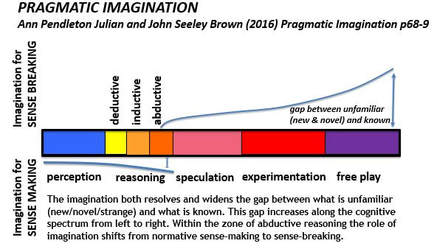

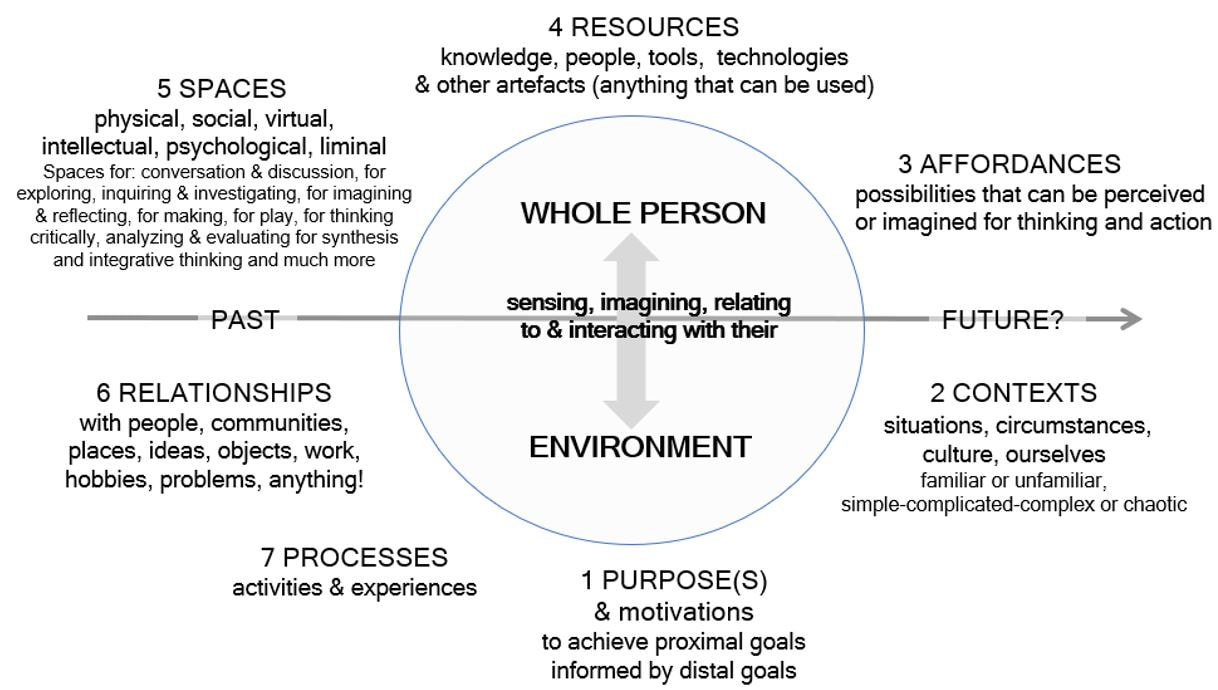

NJ While imagination emerges into our consciousness without any sort of attentive prompting in the everyday circumstances of our life, we can also engage our imagination consciously by creating an ecology of thinking and action that enables us to interact and deal with problem or situation. Imagination has always been an important part of my model or framework for an ecology of learning and practice(4 ) and Figure 1 but recently I have found the idea of pragmatic imagination (5) and more recently, (through Joy Whitton (6), Ricoeur’s theory of imagination (7), useful in explaining how imagination works in an ecology of learning & practice. Through a process of ecological thinking and action, [what Jullian-Pendleton and Brown call ‘pragmatic imagination’ - ‘productive [and purposeful] entanglement of imagination, reasoning [emotion] and action’(5) ] we interpret/assess the situations, decide a course of action and create (Imagine and implement an ecology of practice) the main components of which are illustrated in the model.

Figure 1 An ecology for learning and practice (adapted from Jackson4) The framework or model shows key relationships and interactions between the person and their environment. The ecological framework is a heuristic to help us imagine some of the complexity involved. The labels explain an aspect of the ecology but do not say how they interact. This is revealed in the narrative of the action. The components of the ecology do not stand in isolation. They can and do connect, interfere and be incorporated into each other. In this sense imagination interacts with and modifies each and all of the components in the model.

My involvement motivated me to think about the questions being posed and the supplementary questions that always emerge. It also motivated me to engage in new inquiries which inevitably lead to new discoveries. And of course the range of perspectives and practical illustrations offered by participants encouraged me to see things in a different way to the way I normally think. Half way through the conversation we were challenged to take our imaginations for a walk (see my other blog post) and the result of this was I started a whole new blog on my garden

During the conversation I was paying more attention to my imagination and how it featured in my everyday thinking: I became conscious that it emerged into my consciousness much of the time I was not deliberately thinking about something or doing something that required my cognitive attention. I have been surprised by just how active my imagination is present, it seems to be firing away most of the time but particularly when I’m by myself – like when I was chopping brambles in the garden, a physical task that seemed to provide a good space for imagining. While I was chopping I mentally visited a number of past experiences and anticipated some of the things that were going to happen in the not too distant future – a sort of mental time travel that seemed to happen spontaneously without me making it happen. In this mode my imagination entertained me, engaged me emotionally, reminded me of who I am and who I was in my past life and helped me think about what I needed to do in the near future.

My own deliberate exploration of ‘Using & Cultivating Imagination’ was geared to my more general exploration of the idea of learning ecologies and ecologies of practice. Emerging from the conversation was a deeper appreciation of the way imagination relates to my evolving ideas on learning and practice ecologies we create to achieve something we value. In a learning or practice ecology, imagination is harnessed along with perception, reasoning and reflective processes for a purpose eg to learn or master something, to tackle a problem or deal with a situation, to exploit an opportunity etc.. In the March #creativeHE exploration we focused on ‘creativity in the making’, through several narratives I drew on the ideas of ‘pragmatic’, ‘representational’ and ‘generative’ imagination to try to understand how imagination was involved in particular examples of making.

During the course of the conversation I came across the writings of Stephen Fesmires and his ideas on ‘ecological imagination’(1) made sense to me. This extract from Steven’s 2011 article, 'Ecological Imagination in Moral Education East and West' opens up the idea that imagination is fundamentally ecological in nature. I add my own interpretive commentary (NJ italics) and illustrations to his conceptual elaboration – which is itself a product of a disciplinary pragmatic imagination.

Ecological Imagination Extract (pg 27-28) my responses in italics

Like the terms space, time, and mass to the modern physicist, the terms individual and system signify to the ecologist things and the relationships that synergistically constitute them rather than ultimate existences. Conditions demand that we extend perception deeper into the socio-cultural, natural, and interpersonal relationships in which we are embedded.

Ecological literacy has become essential to this. But even the most thorough knowledge about complex systems will overwhelm rather than enhance moral intelligence if that knowledge is not framed by imagination—here understood not as a faculty but as a function—in a way that relates one‘s individual biography to one‘s encompassing environment and history.

NJ: I think all imagination is ecological in the sense that it relates to, and is the product of interactions with our inner and outer world eg memories, perceptions, reasonings, emotions, experiences and ‘things’ in our real and imagined world.

It might be implicit but I would make more explicit the nature of encompassing environment and history (one’s encompassing past and present environment, personal history and unfolding present). I believe the function of imagination is involved in creating ecologies for learning and practice and is stimulated and put to use in a pragmatic way through an ecology for learning and practice.

….…in order to build a working definition of ecological imagination, it is essential first to better understand (or at least to stipulate) what imagination is and does…. What is imagination from a cognitive standpoint? Cognitive scientists studying the

neural synaptic connections we call imagination define it helpfully as a form of ―mental simulation shaped by our embodied interactions with the social and physical world and structured by projective mental habits like metaphors, images, semantic frames, symbols, and narratives.(2)

What does imagination do? More than a capacity to reproduce mental images, Dewey highlights imagination‘s active and constitutive role in cognitive life. "Only imaginative vision, he urges in Art as Experience, ― elicits the possibilities that are interwoven within the texture of the actual.(3) Only through imagination do we see actual conditions in light of what is possible, so it is fundamental to all genuine thinking—scientific, aesthetic, or moral. It is also an ordinary and integral function of human interaction, not the special province of poets or daydreamers.

NJ While imagination emerges into our consciousness without any sort of attentive prompting in the everyday circumstances of our life, we can also engage our imagination consciously by creating an ecology of thinking and action that enables us to interact and deal with problem or situation. Imagination has always been an important part of my model or framework for an ecology of learning and practice(4 ) and Figure 1 but recently I have found the idea of pragmatic imagination (5) and more recently, (through Joy Whitton (6), Ricoeur’s theory of imagination (7), useful in explaining how imagination works in an ecology of learning & practice. Through a process of ecological thinking and action, [what Jullian-Pendleton and Brown call ‘pragmatic imagination’ - ‘productive [and purposeful] entanglement of imagination, reasoning [emotion] and action’(5) ] we interpret/assess the situations, decide a course of action and create (Imagine and implement an ecology of practice) the main components of which are illustrated in the model.

Figure 1 An ecology for learning and practice (adapted from Jackson4) The framework or model shows key relationships and interactions between the person and their environment. The ecological framework is a heuristic to help us imagine some of the complexity involved. The labels explain an aspect of the ecology but do not say how they interact. This is revealed in the narrative of the action. The components of the ecology do not stand in isolation. They can and do connect, interfere and be incorporated into each other. In this sense imagination interacts with and modifies each and all of the components in the model.

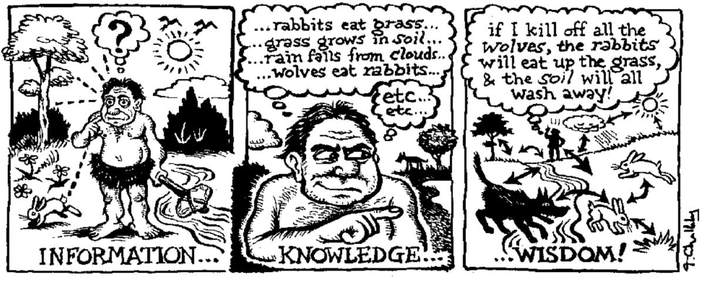

Imagination is essential to the emergence of meaning, a necessary condition for which is to note relationships between things. To take a simple ecological example, many migratory songbirds I enjoy in summer over a cup of coffee are declining in numbers in part because trees in their winter nesting grounds in Central America are bulldozed to plant coffee plantations. Awareness of this amplifies the meaning of my cup of coffee. ―To grasp the meaning of a thing, an event, or a situation, Dewey notes, ― is to see it in its relations to other things (8)

Or, as Mark Johnson recently put it, ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual or potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences.’(9) Meaning is amplified as new connections are identified and discriminated. Ideally, this amplification operates as a means to intelligent and relatively inclusive foresight of the consequences of alternative choices and policies.

NJ This ideas goes to the heart of ecological thinking which I believe is best explained in terms of the idea of pragmatic imagination (4) in which perception, reasoning, imagination, [emotion] and action are all entangled in a productive way to either make sense of a situation or phenomenon or to break existing senses and create entirely new meanings.

Or, as Mark Johnson recently put it, ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual or potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences.’(9) Meaning is amplified as new connections are identified and discriminated. Ideally, this amplification operates as a means to intelligent and relatively inclusive foresight of the consequences of alternative choices and policies.

NJ This ideas goes to the heart of ecological thinking which I believe is best explained in terms of the idea of pragmatic imagination (4) in which perception, reasoning, imagination, [emotion] and action are all entangled in a productive way to either make sense of a situation or phenomenon or to break existing senses and create entirely new meanings.

Or as Mark Johnson recently put it, ‘The meaning of something is its relations, actual or potential, to other qualities, things, events, and experiences.’(9) Meaning is amplified as new connections are identified and discriminated. Ideally, this amplification operates as a means to intelligent and relatively inclusive foresight of the consequences of alternative choices and policies.

NJ The illustration shows this complex process of pragmatic imagination in sense making through human mind – human environment interactions. One can imagine this visualization being created in the mind of early mankind.

NJ The illustration shows this complex process of pragmatic imagination in sense making through human mind – human environment interactions. One can imagine this visualization being created in the mind of early mankind.

What is ecological imagination?

Michael Pollan observes that ―proper names have a way of making visible things we don‘t easily see or simply take for granted.(10) Ecological imagination names a cognitive capacity that tends to be taken for granted by environmental and social advocates. Environmental thinkers have long recognized that ecological thinking helps us to forecast and facilitate outcomes so we can better negotiate increasingly complex systems. Yet little direct attention has been given to theorizing about the imaginative dimension of such thinking. Ecological thinking is fundamentally imaginative, at least in the sense that it requires simulations and projections shaped by metaphors, images, etc. These metaphor-steeped simulations inform choices and policies by piggybacking on our more general deliberative capacity to perceive, in light of imaginatively rehearsed possibilities for thought and action, the relationships that constitute any object on which we are focusing. By means of this general deliberative capacity, relational perceptiveness can enter into practical, aesthetic, and scientific deliberations so that we understand focal objects through connections distant in space and time.

Ecological imagination is a concept too broad to encompass in an essay, but the foregoing suggests a working definition that will suffice to urge its import for moral education. Ecological imagination is here understood as relational imagination shaped by key metaphors used in (though not necessarily originating in) the ecologies. That is, imagination is specifically ―ecological when key metaphors and the like used in the ecologies organize mental simulations and projections. Our deliberations enlist ecological imagination when these imaginative structures (some of recent origin and some millennia old) shape what Dewey calls our dramatic rehearsals.

Michael Pollan observes that ―proper names have a way of making visible things we don‘t easily see or simply take for granted.(10) Ecological imagination names a cognitive capacity that tends to be taken for granted by environmental and social advocates. Environmental thinkers have long recognized that ecological thinking helps us to forecast and facilitate outcomes so we can better negotiate increasingly complex systems. Yet little direct attention has been given to theorizing about the imaginative dimension of such thinking. Ecological thinking is fundamentally imaginative, at least in the sense that it requires simulations and projections shaped by metaphors, images, etc. These metaphor-steeped simulations inform choices and policies by piggybacking on our more general deliberative capacity to perceive, in light of imaginatively rehearsed possibilities for thought and action, the relationships that constitute any object on which we are focusing. By means of this general deliberative capacity, relational perceptiveness can enter into practical, aesthetic, and scientific deliberations so that we understand focal objects through connections distant in space and time.

Ecological imagination is a concept too broad to encompass in an essay, but the foregoing suggests a working definition that will suffice to urge its import for moral education. Ecological imagination is here understood as relational imagination shaped by key metaphors used in (though not necessarily originating in) the ecologies. That is, imagination is specifically ―ecological when key metaphors and the like used in the ecologies organize mental simulations and projections. Our deliberations enlist ecological imagination when these imaginative structures (some of recent origin and some millennia old) shape what Dewey calls our dramatic rehearsals.

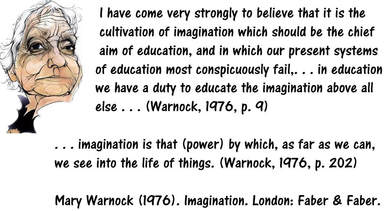

NJ So what does all this mean for education, particularly higher education teaching and learning, and for the institutions that provide opportunities for learning?

A culture‘s understanding of ecosystems is an in-road for revealing how they conceive their place in a matrix of relations.Indeed, the sort of imaginative simulation used to understand an ecosystem is often relevant to our dealings with other complex systems. The horizon of ecological imagination is to a considerable degree structured by metaphors.(11)

There are many conventional metaphors by which English-speakers make sense of ecosystemic relationships (e.g., web, network, community, organism, economic system, field pattern, whole, home, fabric) and trophic relations (e.g., cycles or loops, energy flows, (food) chains/links, pyramids, musical performances). Image-schematic structures such as containment, up-down, balance, and the like also play a vital role.

NJ These metaphors and image schemas can be and are being used to structure the logic about learning and practice in the contemporary world. Unfortunately, higher education generally thinks in terms of linear structures and processes.. courses, with pre-deterimed and predictable outcomes.

My own model of a learning ecology or ecology of practice is an example of how we might encourage the metaphorical language of ecology in learning and teaching. So my own take on using and cultivating imagination in the higher education context is, not surprisingly, connected to the affordances provided for enabling learners to understand learning as an ecological phenomenon and the pedagogical thinking and actions that empower and enable learners to create (imagine and implement) their own ecologies for learning and practice. The first step is for higher education teachers and educational developers to understand the significance in the ideas and conceptual vocabulary, the second is approach teaching and learning in with an ecological mindset.

Sources

1) Steven Fesmires (2011) Ecological Imagination in Moral Education, East and West

Annales Philosophici 2 (2011), pp. 20-34

2) George Lakoff, The Political Mind (New York: Viking Press, 2008), 241. For a bibliography of

research on imagination in cognitive science, see Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy

in the Flesh (New York: Basic Books, 1998).

3) Dewey, Art as Experience, LW 10:348

4) Jackson, N J (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies Chalk Mountain : Lulu

5) Pendleton Julian, A. and Brown, J. S.(2016) Pragmatic Imagination available at:

http://www.pragmaticimagination.com/

6) Whitton J (2018) Fostering Imagination in Higher Education Routledge

7) Ricoeur, P. (1984/85) Time and Narrative. 3 vols. trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

8) Dewey, How We Think, LW 8:225.

9) Mark Johnson, The Meaning of the Body (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 265.

10) Michael Pollan, In Defense of Food (New York: Penguin, 2008), 28.

11) For an analysis of the metaphorical structuring of ecological imagination, see my ―Ecological Imagination, Environmental Ethics 32 (Summer 2010):183-203

A culture‘s understanding of ecosystems is an in-road for revealing how they conceive their place in a matrix of relations.Indeed, the sort of imaginative simulation used to understand an ecosystem is often relevant to our dealings with other complex systems. The horizon of ecological imagination is to a considerable degree structured by metaphors.(11)

There are many conventional metaphors by which English-speakers make sense of ecosystemic relationships (e.g., web, network, community, organism, economic system, field pattern, whole, home, fabric) and trophic relations (e.g., cycles or loops, energy flows, (food) chains/links, pyramids, musical performances). Image-schematic structures such as containment, up-down, balance, and the like also play a vital role.

NJ These metaphors and image schemas can be and are being used to structure the logic about learning and practice in the contemporary world. Unfortunately, higher education generally thinks in terms of linear structures and processes.. courses, with pre-deterimed and predictable outcomes.

My own model of a learning ecology or ecology of practice is an example of how we might encourage the metaphorical language of ecology in learning and teaching. So my own take on using and cultivating imagination in the higher education context is, not surprisingly, connected to the affordances provided for enabling learners to understand learning as an ecological phenomenon and the pedagogical thinking and actions that empower and enable learners to create (imagine and implement) their own ecologies for learning and practice. The first step is for higher education teachers and educational developers to understand the significance in the ideas and conceptual vocabulary, the second is approach teaching and learning in with an ecological mindset.

Sources

1) Steven Fesmires (2011) Ecological Imagination in Moral Education, East and West

Annales Philosophici 2 (2011), pp. 20-34

2) George Lakoff, The Political Mind (New York: Viking Press, 2008), 241. For a bibliography of

research on imagination in cognitive science, see Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy

in the Flesh (New York: Basic Books, 1998).

3) Dewey, Art as Experience, LW 10:348

4) Jackson, N J (2016) Exploring Learning Ecologies Chalk Mountain : Lulu

5) Pendleton Julian, A. and Brown, J. S.(2016) Pragmatic Imagination available at:

http://www.pragmaticimagination.com/

6) Whitton J (2018) Fostering Imagination in Higher Education Routledge

7) Ricoeur, P. (1984/85) Time and Narrative. 3 vols. trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

8) Dewey, How We Think, LW 8:225.

9) Mark Johnson, The Meaning of the Body (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 265.

10) Michael Pollan, In Defense of Food (New York: Penguin, 2008), 28.

11) For an analysis of the metaphorical structuring of ecological imagination, see my ―Ecological Imagination, Environmental Ethics 32 (Summer 2010):183-203

RSS Feed

RSS Feed