These are some of the ideas that I thought about as the #creativeHE conversation unfolded, I will keep adding to them as I reflect. I don’t think it’s easy to talk about our practice in ways that enable other people to get inside it and it’s even harder to talk about one’s own creativity. Narratives of personal experiences annotated by the individual's own interpretations and reflections seem to provide the most useful way in and we were fortunate in having a number of stories that enabled me to develop my thinking.

Whenever I think about creativity in practice I make the assumption that everyone is unique, shaped by a life that only they have experienced. Therefore the way they involve themselves in a domain or field of practice, including their creative involvement, will also be unique, although their practice will be influenced by what other practitioners do in that field.

I often think its much easier to demonstrate creativity when there is a tangible product arising from practice. Its one of the reasons why we associate creativity with artistic expression. Its far more difficult to demonstrate creativity when, for example, its a course of action and conversation that brings about a change or new practice in an organisation. Conversations about creativity often reflect this bias.

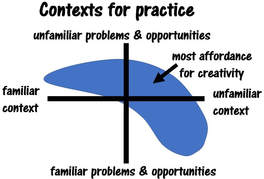

Is creativity transferable? Well our ability to imagine and connect and combine things in novel ways, and to be resourceful can probably be applied in lots of different contexts across our lives, but we cannot suddenly jump into a domain we know nothing about and expect to perform competently and creatively.

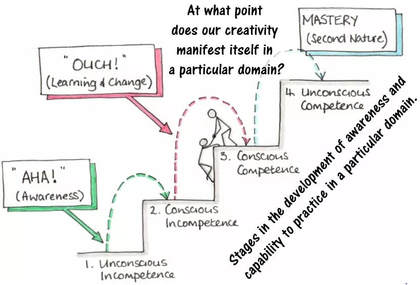

During the conversation we tried to explore what happens when a person enters a domain for the first time with no domain specific knowledge or skill – at what point will they be able to draw upon their creativity? By domain, I mean a discrete area of practice replete with its own contexts, situations, cultural expectations, demands, problems and opportunities, knowledge and skill requirements, and experiences.

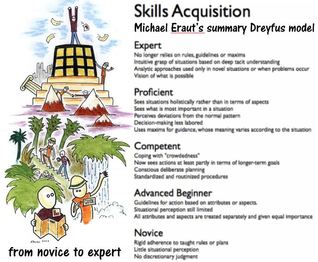

We considered the Dreyfus model - the journey from novice to expert as we enter, learn and develop, and eventually gain some expertise in a domain. There was a sense that while this model works in some domains, where there are clearly defined stages in education and training, it was too hierarchical as a general way of explaining the development of a person to perform in a domain.

Much has been written about the relationship between practice and top ‘creative’ performers in fields like music, sport and chess and Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea that "ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness." This idea has been criticized by many researchers in the field of creativity.

The originator of the idea Anders Ericsson argue's the idea is more nuanced. He shows that deliberate practice can indeed help people master complex skills. Deliberate practice involves a series of techniques designed to learn efficiently and purposefully. This involves goal setting, breaking down complex tasks into chunks, developing highly complex and sophisticated representations of possible scenarios, getting out of your comfort zone, and receiving constant feedback. But according to these authors deliberate practice is most applicable to "highly developed fields" such as chess, sports, and musical performance in which the rules of the domain are well established and passed on from generation to generation. The principles of deliberate practice do not work nearly as well for professions in which there is "little or no direct competition, such as gardening and other hobbies", and "many of the jobs in today's workplace-- business manager, teacher, electrician, engineer, consultant, and so on."

When my two personal tales of creativity (see earlier posts) are viewed from this perspective it is not surprising that I could create a picture that gave me a sense of joy and fulfilment in a medium I had never painted in before without any previous practice in that medium, but I was a million miles away from expressing myself creatively through the production of a mix following the recording of my band because I had not practised enough to understand how to mix a 16 track recording in a domain that requires a lot of technical know how.

Being creative is a conscious and deliberate act, in order for a person to be creative in a domain they have to be able to see the affordance in situations to be able to act creatively. Perceiving is a lot more than just seeing. Jenny Willis drew my attention to the idea of ‘seeing with memory’. If we have not developed the memory from experiences in a domain how can we see in that domain?

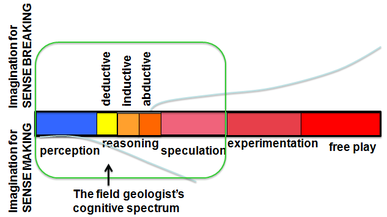

We can extend this reasoning to the full cognitive spectrum used by an experienced practitioner in any domain. When someone with domain knowledge, skill and experience (memory) tackles a challenging problem they work backwards and forwards along the cognitive spectrum perceiving (observing and comprehending informed by knowledge gained through study and experience), imagining (conceptualizing what is observed in order to create possible meanings and perhaps extending or modifying those meanings), and reasoning (the critical evaluation of what is perceived or imagined in order to evaluate possible meanings and make judgements) and reflecting on what has been seen and understood to try to develop more meaning from it. All these mental processes are harnessed in a process that involves creativity but to perceive, reason and imagine requires domain-specific knowledge and experience.

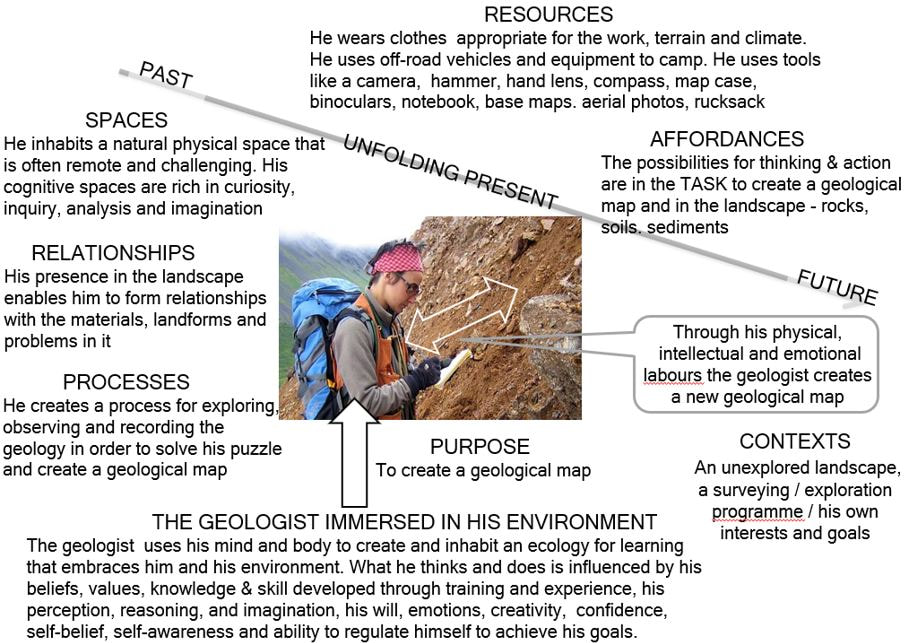

I tried to give a practical illustration of this process in my account of a geologist making a geological map. The mental processes of perceiving, imagining and reasoning enable the geologist to develop hypotheses about what is being perceived and these are intermingled with the actions and activities that enable him to test his theories, to find the pieces of the geological puzzle (rock outcrops and structures), sense (observe, feel, hear, test, measure) the materials, and record (often sketching or photographing and making notes) what has been perceived. In this way ideas about the geology are tested, advanced or abandoned.

For these reasons, and with this practical illustration in mind, I concluded that our ability to be creative in a domain specific way, really only begins when we reach the conscious competency level in the awareness / competency model outlined above: when a practitioner has the awareness to not only read a situation but to imagine and play with it. This does not have to apply to the whole of the domain but to areas of practice within the domain where an appropriate level of awareness and competency has been reached.

My own experiences, and those shared by participants, tell me that we can use our small-c creativity in lots of different practices across our life but we can express ourselves more quickly in some domains than others. My stories of trying to record and mix and trying to create a digital picture on the ipad illustrate this. I need to develop a lot more knowledge, skill and awareness for the former than the latter in order to use my creativity. This simple example tells us that some domains are more complex in terms of their demand for knowledge, skill and the complexity of thinking and action required to perform.

This is particularly the case of professional domains like for example being a teacher or a doctor. Furthermore, admission to a professional domain might be heavily protected with strict requirements to follow a regime of education, training and certification and following entry commitments to CPD. So the journey to levels of awareness and competency where creativity can be used, is much quicker and less arduous in some domains than others.

Creativity in professional practice can be simple small-c expressions but to achieve anything complex, significant and challenging – things that have not been attempted before, require imagination (vision) and a constellation of practices that have to be planned, implemented, connected and effects harnessed. This orchestration of practices over time to achieve a complex goal is best though of as an ecology of practice. John Rea described his ecology of practice beautifully and I illustrated an ecology of practice that a geologist might create to produce a geological map.

When we enter a new domain we do not know how to create an ecology of practice. We are not expected to know this. What we are expected to know is how to learn in that domain and if we don’t know we will be shown or we have to find out for ourselves. We begin a process of being a practitioner and becoming a more expert practitioner in that field. Eventually, we take on our own projects and apply what we have learnt as an independent and autonomous practitioner developing our own ecology of practice within which our learning and creativity are embedded.

Concepts and theories for creativity in practice

Glaveneau et al (3) propose an action framework for the analysis of creative acts built on the assumption that creativity is a relational, inter-subjective phenomenon. Results point to complex models of action and inter-action specific for each domain and also to interesting patterns of similarity and differences between domains. These findings highlight the fact that creative action takes place not “inside” individual creators but “in between” actors and their environment.

Human action is defined by its intentionality and the mediation of various systems of tools, signs, and artifacts that make it comprehensible and symbolic. It takes place in a setting and involves both the organism, in its unity between body and mind, and a socioculturally constructed environment. Finally, action is often joint action and is both facilitated by and facilitates human social relations (3:2)

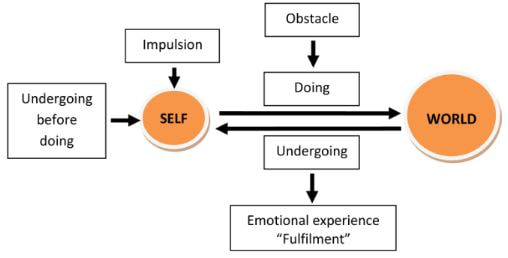

I agree with this ecological view of a whole person or persons purposefully interacting with their environment in particular ways that encourages creativity to emerge. Glaveneau et al based their action framework on John Dewey’s model of interaction (4). “Action starts, as depicted, with an impulsion and is directed toward fulfillment. In order for action to constitute experience though, obstacles or constraints are needed. Faced with these challenges, the person experiences emotion and gains awareness (of self, of the aim, and path of action). Most importantly, action is structured as a continuous cycle of “doing” (actions directed at the environment) and “undergoing” (taking in the reaction of the environment). Undergoing always precedes doing and, at the same time, is continued by it. It is through these interconnected processes that action can be taken forward and become a “full” experience “(2:2-3).

Where do our impulses come from? Well the stories that were shared all give their reasons for why a particular course of action was initiated and sustained and it is very much to do with fulfilling purposes that are often bigger than yourself. You can see the elements of the Dewey model in all the stories of creativity in practice that were shared.

Considering the narratives of creativity that were volunteered during the discussion the definition of personal creativity proposed by Carl Rogers (5) would fit this action framework and my working concept of ecologies of practice namely, ‘the emergence in action of a novel relational product growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, or circumstances of their life’. In my narrative (6) of a field geologist using his practice to create a geological map - a creative artefact in the domain of geology I tried to demonstrate how the production of the artefact emerges through his ecology of practice as he interacts in a purposeful manner with the environment in which he works.

Sources

1 Gladwell M (2008) Outliers: The Story of Success Penguine

2 Ericson A and Pool R (2016) Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise Hardcover Eamon Dolan/ Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

3 Glaveanu, Todd Lubart, Nathalie Bonnardel, Marion Botella, Pierre-Marc de Biaisi, Myriam Desainte-Catherine, Asta Georgsdottir, Katell Guillou, Gyorgy Kurtag, Christophe Mouchiroud, Martin Storme, Alicja Wojtczuk and Franck Zenasni (2013) Creativity as action: findings from five creative domains (2013) Frontiers of Psychology v4 1-14

4 Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Penguin.

5 Rogers, C.R., (1960) On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

6 Jackson N J (2017) An Ecology of Practice - Making a Geological Map (copy below)

| ecology_of_practice_a_geologist.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed