Today we focused on how we learn to practice and at what point in the process are we able to use our creativity. To perform and practice effectively in any field involves developing certain knowledge, skills, behaviours, self-awareness and ways of thinking and interpreting the situations that are relevant to that particular practice. Such skills and understandings are developed over time through practise and experience. The questions I posed to initiate the conversation were:

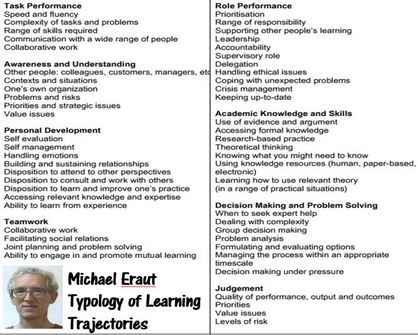

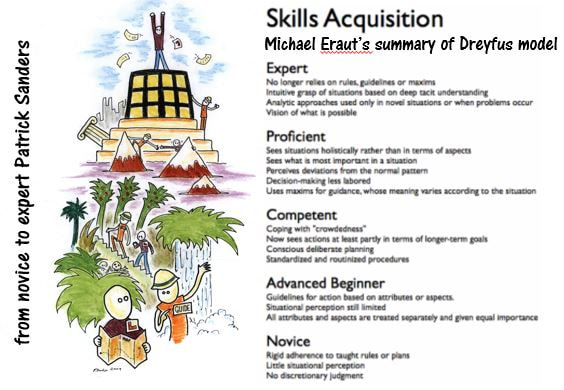

How do we learn and develop entirely new practices? At what point do we feel we can use our creativity in this developmental process? Is there a consistent pattern in how we develop new practice? eg the Dreyfus model from novice to expert. If there is, how does creativity feature in this process? I provided a copies of the Dreyfus novice to expert model and Michael Earut's 'How professionals learn through work' as research-based resources.

How do we learn and develop entirely new practices? At what point do we feel we can use our creativity in this developmental process? Is there a consistent pattern in how we develop new practice? eg the Dreyfus model from novice to expert. If there is, how does creativity feature in this process? I provided a copies of the Dreyfus novice to expert model and Michael Earut's 'How professionals learn through work' as research-based resources.

It’s always an anxious moment when you start an online conversation – will anyone join in? So I was relieved and grateful to Paul Klieman for setting the ball rolling..

“Hello Norman and everyone, The ‘from Novice to Expert’ is intriguing when I think of part of the research I undertook for my doctorate. I asked colleagues, via a questionnaire, for the words and phrases they used when describing creativity or ‘being creative’. The c. 2500 words and phrases that resulted (from 81 individuals) fell into five main categories in descending order: Thinking, Making, Doing, Solving, Dreaming. Now, I can see how the Novice to Expert applies to ‘Making’ and ‘Doing’, but I’m not sure how it applies to the others. Is N➡️E consistent across the range? E.g. to be an Expert ‘Maker’ does one have to be an expert ‘Thinker’ etc. There are many Expert craftspeople who rigidly follow taught rules etc. Just some early morning thoughts.......”

My thoughts were, perhaps it depends on context and the levels of complexity involved in practice. Making a simple artefact might require only limited thinking relating to replication but producing artefacts on a commercial scale would involve a lot more variables to be juggled and balanced and a lot more interactions to be orchestrated. Paul had a point that the idea of progressing from an absolute beginner to expert has to be contextualized in real situations and practices for it to be meaningful and comprehendible. I suspect that all of Paul’s categories could be involved (perhaps substituting imagining for dreaming).

David Andrew thought the novice to expert model “suggests a linear development from novice to expert, a model that pervades current views of education, concepts such as learning gain being hugely popular, and in my view dangerous. It also doesn't reflect much of the research, for example in chess players, which shows that experts are not better at doing what novices struggle with, but that they do different things”. Paul agreed, “Yes, it’s the linearity and implied hierarchy (it’s in the language) that bothers me. I would not wish my ‘expert’ surgeon to no longer ‘rely on rules and guidelines’, though I would hope that should some need to improvise occur he/she would use their ‘expertness’ to deal with it successfully. And, yes of course, context is all. An expert in a highly specialised field may be a complete novice in all others.”

In an attempt to encourage others I shared a personal story. Over a year ago I decided, with a friend, that we wanted to learn how to record our band. We purchased a second hand ‘digital mixer’ and had a go at trying to get it to talk to the computer which hosted the processing software, but we didn’t manage to make it work. Other things then got in the way and we left it. A year later, feeling quite ashamed at our lack of progress, we resurrected the idea with a different level of motivation and over three or four weeks, and quite a lot of time and effort, and some expert help, we reinstalled the software and managed to get it to work, we set up the mixer and recorded our band and fumbled to do some post-recording mixing on the computer.

I have found that the biggest source of help and aid to learning is not the 350 page manual but google. When I reach a block I type my query into google and either the relevant page comes in my manual comes up, or I find a forum where the problem has been discussed and often resolved or I find a video on YouTube that gives me an answer that demonstrates the practice which I can then imitate. Copying in order to do something is the way I'm learning to practice at the moment and there is no creativity involved as far as I can tell.

When it comes to developing the knowledge and skill to record and mix our music I am at the very start of my journey. Trying to get to the next level of understanding and competency is a painfully slow learning curve with every procedure needing to be looked up and practised by imitating what I had seen. Nothing is intuitive and nothing is automated and I am often in a state of perplexity – what do I do next? and anxiety - when I think I have done something wrong to the recording equipment. Perhaps another way of representing this state is through the well known journey to competency matrix. This is often attributed to Maslow but it does not appear in any of his works so is best attributed to Noel Burch. As far as recording and mixing is concerned, I am at the start of a long learning curve so I place myself in the conscious incompetence category and I know I will have to put considerable time and effort in my learning project to reach the conscious competence level.

Since being creative is a conscious and deliberate act, I am wondering whether our ability to be creative in a particular domain is essentially limited to the right hand field of this matrix. Adapting the notes on wiikipedia would yield the following scenario.

Unconscious incompetence - The individual does not understand or know how to do something and does not necessarily recognize the deficit. They may deny the usefulness of the skill. The individual must recognize their own incompetence, and the value of the new skill, before moving on to the next stage. At this stage there is no reason or capacity for creativity.

Conscious incompetence - The individual is interested in developing the knowledge and skill. Although they do not understand or know how to do something, they recognize the deficit, as well as the value of a new skill in addressing the deficit. They make a start. There is a lot to learn and a lot of the learning is through following instructions and imitating people who can already do these things. Making mistakes is an integral and necessary way of learning. Confidence grows as learning is applied and new procedures are tried. There is little opportunity for the individual to be creative at this stage although they might be driven by a desire to eventually use their developing skills in a creative way.

Conscious competence - The individual understands or knows how to do something. However, demonstrating the skill or knowledge requires concentration and effort. It may be broken down into steps, and there is heavy conscious involvement in executing the new skill. The individual can begin to reason solutions to problems and they can also see the progress they have made. They are now in a position to experiment with a degree of confidence and make use of their creativity in the process.

Unconscious competence - The individual has had so much practise with a skill that it has become "second nature" and can be performed easily. As a result, the skill can be performed while executing another task. Furthermore, the individual can see and appreciate how all the tasks in a sustained project are connected. They can see and imagine the whole rather than only the individual parts. Different approaches and actions can be imagined and their effects anticipated. Problems can be visualized in different ways opening up more possibilities for solution and quicker routines for problem solving. An individual is able to make good use of their creativity in their practices.

“Hello Norman and everyone, The ‘from Novice to Expert’ is intriguing when I think of part of the research I undertook for my doctorate. I asked colleagues, via a questionnaire, for the words and phrases they used when describing creativity or ‘being creative’. The c. 2500 words and phrases that resulted (from 81 individuals) fell into five main categories in descending order: Thinking, Making, Doing, Solving, Dreaming. Now, I can see how the Novice to Expert applies to ‘Making’ and ‘Doing’, but I’m not sure how it applies to the others. Is N➡️E consistent across the range? E.g. to be an Expert ‘Maker’ does one have to be an expert ‘Thinker’ etc. There are many Expert craftspeople who rigidly follow taught rules etc. Just some early morning thoughts.......”

My thoughts were, perhaps it depends on context and the levels of complexity involved in practice. Making a simple artefact might require only limited thinking relating to replication but producing artefacts on a commercial scale would involve a lot more variables to be juggled and balanced and a lot more interactions to be orchestrated. Paul had a point that the idea of progressing from an absolute beginner to expert has to be contextualized in real situations and practices for it to be meaningful and comprehendible. I suspect that all of Paul’s categories could be involved (perhaps substituting imagining for dreaming).

David Andrew thought the novice to expert model “suggests a linear development from novice to expert, a model that pervades current views of education, concepts such as learning gain being hugely popular, and in my view dangerous. It also doesn't reflect much of the research, for example in chess players, which shows that experts are not better at doing what novices struggle with, but that they do different things”. Paul agreed, “Yes, it’s the linearity and implied hierarchy (it’s in the language) that bothers me. I would not wish my ‘expert’ surgeon to no longer ‘rely on rules and guidelines’, though I would hope that should some need to improvise occur he/she would use their ‘expertness’ to deal with it successfully. And, yes of course, context is all. An expert in a highly specialised field may be a complete novice in all others.”

In an attempt to encourage others I shared a personal story. Over a year ago I decided, with a friend, that we wanted to learn how to record our band. We purchased a second hand ‘digital mixer’ and had a go at trying to get it to talk to the computer which hosted the processing software, but we didn’t manage to make it work. Other things then got in the way and we left it. A year later, feeling quite ashamed at our lack of progress, we resurrected the idea with a different level of motivation and over three or four weeks, and quite a lot of time and effort, and some expert help, we reinstalled the software and managed to get it to work, we set up the mixer and recorded our band and fumbled to do some post-recording mixing on the computer.

I have found that the biggest source of help and aid to learning is not the 350 page manual but google. When I reach a block I type my query into google and either the relevant page comes in my manual comes up, or I find a forum where the problem has been discussed and often resolved or I find a video on YouTube that gives me an answer that demonstrates the practice which I can then imitate. Copying in order to do something is the way I'm learning to practice at the moment and there is no creativity involved as far as I can tell.

When it comes to developing the knowledge and skill to record and mix our music I am at the very start of my journey. Trying to get to the next level of understanding and competency is a painfully slow learning curve with every procedure needing to be looked up and practised by imitating what I had seen. Nothing is intuitive and nothing is automated and I am often in a state of perplexity – what do I do next? and anxiety - when I think I have done something wrong to the recording equipment. Perhaps another way of representing this state is through the well known journey to competency matrix. This is often attributed to Maslow but it does not appear in any of his works so is best attributed to Noel Burch. As far as recording and mixing is concerned, I am at the start of a long learning curve so I place myself in the conscious incompetence category and I know I will have to put considerable time and effort in my learning project to reach the conscious competence level.

Since being creative is a conscious and deliberate act, I am wondering whether our ability to be creative in a particular domain is essentially limited to the right hand field of this matrix. Adapting the notes on wiikipedia would yield the following scenario.

Unconscious incompetence - The individual does not understand or know how to do something and does not necessarily recognize the deficit. They may deny the usefulness of the skill. The individual must recognize their own incompetence, and the value of the new skill, before moving on to the next stage. At this stage there is no reason or capacity for creativity.

Conscious incompetence - The individual is interested in developing the knowledge and skill. Although they do not understand or know how to do something, they recognize the deficit, as well as the value of a new skill in addressing the deficit. They make a start. There is a lot to learn and a lot of the learning is through following instructions and imitating people who can already do these things. Making mistakes is an integral and necessary way of learning. Confidence grows as learning is applied and new procedures are tried. There is little opportunity for the individual to be creative at this stage although they might be driven by a desire to eventually use their developing skills in a creative way.

Conscious competence - The individual understands or knows how to do something. However, demonstrating the skill or knowledge requires concentration and effort. It may be broken down into steps, and there is heavy conscious involvement in executing the new skill. The individual can begin to reason solutions to problems and they can also see the progress they have made. They are now in a position to experiment with a degree of confidence and make use of their creativity in the process.

Unconscious competence - The individual has had so much practise with a skill that it has become "second nature" and can be performed easily. As a result, the skill can be performed while executing another task. Furthermore, the individual can see and appreciate how all the tasks in a sustained project are connected. They can see and imagine the whole rather than only the individual parts. Different approaches and actions can be imagined and their effects anticipated. Problems can be visualized in different ways opening up more possibilities for solution and quicker routines for problem solving. An individual is able to make good use of their creativity in their practices.

Stumbling towards something

A little later in the conversation Paul Kleiman introduced the idea of 'stumbling' in practices that sometimes led to creativity.

“My occasional blog (I really MUST start writing again) is called ‘Stumbling with Confidence’. That also came out of my research and the in-depth interviews I undertook as part of that research. The interviews always started with asking the individual to talk about what they would consider to be a creative experience in regard to learning and teaching. Once they had recounted the story, I asked them what made them pursue that particular course of action. So many times the answer would be “I stumbled across something” or something similar. As we stumble across ‘stuff’ all the time I was intrigued why a particular ‘stumbling’ led to something tangible and creative. The key ingredient was CONFIDENCE. Having whatever it takes to just ‘have a go’, but also having the confidence to deal any consequences including that it may not work out."

Paula Nottingham suggested that “the idea of ‘stumbling’ works well with the automatic – but the questions is [really about] the awareness of when you have reached your destination”. I agreed that being aware or conscious of what you were doing, even if not why you were doing it, and being able to recognize the significance of what was encountered along the way was important in this discussion. There is a great difference between stumbling with the awareness that comes from a level of knowing and understanding, and the stumbling we do when we don't really know what we are doing. As I am doing in my learning to record and mix story. I think there is something important here to the story of when our creativity becomes significant in our practices and how it emerges as we try things out and stumble across something that we are able to recognise as being meaningful and significant.

A little later in the conversation Paul Kleiman introduced the idea of 'stumbling' in practices that sometimes led to creativity.

“My occasional blog (I really MUST start writing again) is called ‘Stumbling with Confidence’. That also came out of my research and the in-depth interviews I undertook as part of that research. The interviews always started with asking the individual to talk about what they would consider to be a creative experience in regard to learning and teaching. Once they had recounted the story, I asked them what made them pursue that particular course of action. So many times the answer would be “I stumbled across something” or something similar. As we stumble across ‘stuff’ all the time I was intrigued why a particular ‘stumbling’ led to something tangible and creative. The key ingredient was CONFIDENCE. Having whatever it takes to just ‘have a go’, but also having the confidence to deal any consequences including that it may not work out."

Paula Nottingham suggested that “the idea of ‘stumbling’ works well with the automatic – but the questions is [really about] the awareness of when you have reached your destination”. I agreed that being aware or conscious of what you were doing, even if not why you were doing it, and being able to recognize the significance of what was encountered along the way was important in this discussion. There is a great difference between stumbling with the awareness that comes from a level of knowing and understanding, and the stumbling we do when we don't really know what we are doing. As I am doing in my learning to record and mix story. I think there is something important here to the story of when our creativity becomes significant in our practices and how it emerges as we try things out and stumble across something that we are able to recognise as being meaningful and significant.

Learning trajectories, contexts and complexity

Paul Kleiman found my story interesting. “It accords with the Creative Continuum that I have been using for a long time now, which runs from Replication (‘I do, you copy) at one end, through Formulation (‘Yes, there are rules and guidelines but also flexibility’), Innovation (combining existing materials etc into new forms) to Origination (the genuinely and completely new which can also be the, initially rejected, ‘shock of the new’). There is no hierarchy, and as your experience shows, both within and across our various and very varied practices we move constantly one way and t’other along that continuum".

His comments reminded me of Michael Eraut’s model of learning trajectories in complex professional roles where practitioners are developing or regressing along different trajectories according to the nature of the work they are doing and the experiences they are having in their practices. So might this mean that our opportunities for using our creativity are also waxing and waning along similar lines. In any complex role there will be aspects where the work is routine and perhaps unchallenging where opportunities or motivations for using creativity are limited, while other work might be unfamiliar and challenging with lots of opportunity and motivations for personal creativity.

Paul Kleiman found my story interesting. “It accords with the Creative Continuum that I have been using for a long time now, which runs from Replication (‘I do, you copy) at one end, through Formulation (‘Yes, there are rules and guidelines but also flexibility’), Innovation (combining existing materials etc into new forms) to Origination (the genuinely and completely new which can also be the, initially rejected, ‘shock of the new’). There is no hierarchy, and as your experience shows, both within and across our various and very varied practices we move constantly one way and t’other along that continuum".

His comments reminded me of Michael Eraut’s model of learning trajectories in complex professional roles where practitioners are developing or regressing along different trajectories according to the nature of the work they are doing and the experiences they are having in their practices. So might this mean that our opportunities for using our creativity are also waxing and waning along similar lines. In any complex role there will be aspects where the work is routine and perhaps unchallenging where opportunities or motivations for using creativity are limited, while other work might be unfamiliar and challenging with lots of opportunity and motivations for personal creativity.

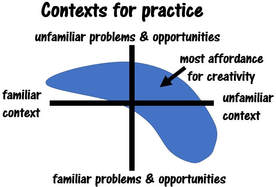

Taking this reasoning a step further I can connect these ideas to John Stephenson’s 2x2 matrix (left) that explains why our main opportunities for creativity lie in those aspects of our lives (or practices) where the contexts and problems or opportunities are unfamiliar. It is in these areas that we are forced to think differently and with imagination and often adapt existing practices or invent new practices.

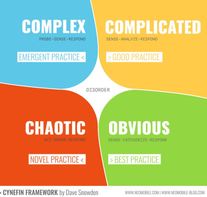

We might also marry this context map to levels of complexity in the context. Dave Snowden's framework (right) for understanding complexity in any situation is helpful here. On day 2 Sandra Sinfield shared a story that showed how she was developing new practice (creativity as practice).

“I hesitated to respond cos I have mentioned this before - but how I learned to be creative in my practice was first to create a space for something to emerge - I let myself follow a path I knew not where - I gave myself permission to stumble - and take creative leaps. In practice this meant that after not really drawing anything at all for over 30 years, I started doing a daily water colour for the first ten minutes on arriving at my office each day ... I really got into this - and experimented with 'blind drawing' and more water colouring... Unexpectedly - this not only provided a meditative space to decrease my stress, but it also increased my joy and my self confidence. So, I enrolled on an #artmooc (a big leap of faith) - and each week as I practised what we had to practise - I also asked: How might I use this in my teaching (practice)? I took another #artmooc and continued this process... Just now I am on a F2F art class with the specific goal of taking lessons learned back to my EdDev practice.

Her story illustrates how in some areas of newly formed practice we can make use of our creativity very quickly and gain satisfaction and joy from the experience and what we produce. Her story shows how we can help ourselves by creating the right environment and circumstances to enable our creativity to flourish, and exploit opportunities in the environment for further development. It also reveals the value of practising the skills in a disciplined way so that practice develops and confidence grows. And as it develops we see and find more opportunity to use it. Perhaps this is a general pattern for the way we develop and sustain new practice and grow our ability to be creative within our practice.

“I hesitated to respond cos I have mentioned this before - but how I learned to be creative in my practice was first to create a space for something to emerge - I let myself follow a path I knew not where - I gave myself permission to stumble - and take creative leaps. In practice this meant that after not really drawing anything at all for over 30 years, I started doing a daily water colour for the first ten minutes on arriving at my office each day ... I really got into this - and experimented with 'blind drawing' and more water colouring... Unexpectedly - this not only provided a meditative space to decrease my stress, but it also increased my joy and my self confidence. So, I enrolled on an #artmooc (a big leap of faith) - and each week as I practised what we had to practise - I also asked: How might I use this in my teaching (practice)? I took another #artmooc and continued this process... Just now I am on a F2F art class with the specific goal of taking lessons learned back to my EdDev practice.

Her story illustrates how in some areas of newly formed practice we can make use of our creativity very quickly and gain satisfaction and joy from the experience and what we produce. Her story shows how we can help ourselves by creating the right environment and circumstances to enable our creativity to flourish, and exploit opportunities in the environment for further development. It also reveals the value of practising the skills in a disciplined way so that practice develops and confidence grows. And as it develops we see and find more opportunity to use it. Perhaps this is a general pattern for the way we develop and sustain new practice and grow our ability to be creative within our practice.

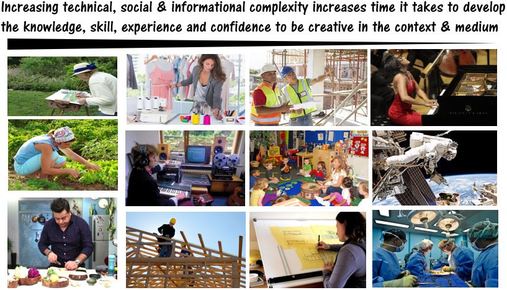

So the journey from inexperienced absolute beginner to more experienced and expert practitioner (or the journey to conscious competence as represented above) is different for every domain and field of practice. It may be simple and sequential (eg in the case of learning or relearning to paint pictures) or long and arduous involving a multiplicity of journeys involving situations and projects of varying levels of challenge, risk, uncertainty and complexity within which an individual’s opportunities and motivations for creativity vary enormously (the journey to a neurological surgeon comes to mind). In this way the purpose and goals of practice, and the contexts and environments in which practice takes place exert an important influence on both the affordance for creativity, the nature of creativity and our willingness and need to use our creativity. Which brings us nicely to our theme for day 2 of our conversation.

Footnote

Chrissi Nerantzi opened a new area of inquiry wondering, “how much or if we really learn from an "expert"? and/or what needs to happen to enable this. Thinking of the distance the word "expert" even, can create...” I could readily relate my story to this comment as a member of our band is pretty nifty on the mixer but he assumes so much and doesn't share his thinking out loud so it's not easy to learn from him. I end up photographing the settings on the mixer and either just accepting them or trying to work out as to why they have been set. Perhaps we learn from experts when we can already think and act with a good degree of proficiency, and more importantly ask the right questions and make sense of what they are doing and how they are doing it.

Chrissi’s question prompted the idea that in order to teach, a person’s expertise in a field needs to be complemented by a willingness to help others who are less expert to learn. My wife who is a GP exemplifies this very well and there is a culture amongst medics of - see one, do one, teach one. At the very least advanced learners need to put themselves in the shoes of the less advanced learner and see the world as they see it. To perform this role well - expert practitioners also have to devote time and effort to developing themselves to fulfil this role. Disciplinary HE teachers provide a good example - and perhaps the cognitive apprenticeships that learners serve in higher education, and the way they develop practice through signature experiences that are relevant to practice in a particular field, connects this question to HE teaching and learning practices. So for HE teachers (advanced learners) the question becomes ‘How can I help/enable my students (less advanced learners) to think and practice in a particular way? This connects to the idea of signature pedagogy and signature learning experiences in a discipline.

Chrissi Nerantzi opened a new area of inquiry wondering, “how much or if we really learn from an "expert"? and/or what needs to happen to enable this. Thinking of the distance the word "expert" even, can create...” I could readily relate my story to this comment as a member of our band is pretty nifty on the mixer but he assumes so much and doesn't share his thinking out loud so it's not easy to learn from him. I end up photographing the settings on the mixer and either just accepting them or trying to work out as to why they have been set. Perhaps we learn from experts when we can already think and act with a good degree of proficiency, and more importantly ask the right questions and make sense of what they are doing and how they are doing it.

Chrissi’s question prompted the idea that in order to teach, a person’s expertise in a field needs to be complemented by a willingness to help others who are less expert to learn. My wife who is a GP exemplifies this very well and there is a culture amongst medics of - see one, do one, teach one. At the very least advanced learners need to put themselves in the shoes of the less advanced learner and see the world as they see it. To perform this role well - expert practitioners also have to devote time and effort to developing themselves to fulfil this role. Disciplinary HE teachers provide a good example - and perhaps the cognitive apprenticeships that learners serve in higher education, and the way they develop practice through signature experiences that are relevant to practice in a particular field, connects this question to HE teaching and learning practices. So for HE teachers (advanced learners) the question becomes ‘How can I help/enable my students (less advanced learners) to think and practice in a particular way? This connects to the idea of signature pedagogy and signature learning experiences in a discipline.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed