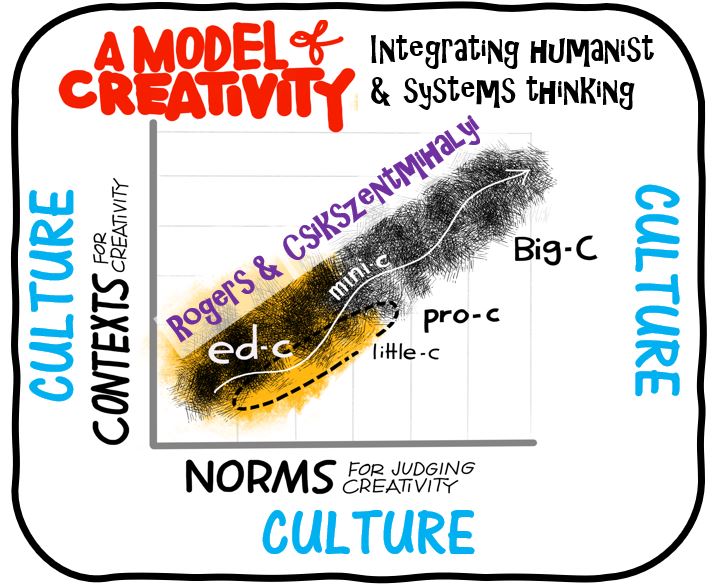

I believe that trying to understand creativity involves navigating and integrating two complementary philosphies, concepts and definitions. Whenever we have a discussion about creativity on the #creativeHE forum www.facebook.com/groups/creativeHE there is always a tussle between humanistic individualistic views of creativity and systemic / cultural views. Such discussions often pitch little-c against Big-c and pro-c (2). The two different philosophies on the phenomenon of creativity and the way we perceive and define it are captured in the thinking and writings of 1) Carl Rogers who approaches creativity from a humanist, person- and individual- centred therapeutic perspective and 3) Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi who approaches creativity through the lens of individuals acting in systems and cultures. Both of these writers recognise the importance of environment in shaping the creative responses of individuals.

Kristen Bettencourt (4) neatly captures the philosophies of these thinkers and these notes are taken from her excellent article.

Rogers (2) defines the creative process as “the emergence in action of a novel relational product, growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, people, or circumstances on the other” (p. 251). Rogers points out, “the very essence of the creative is its novelty, and hence we have no standard by which to judge it” (p.252). Rogers leaves room in the definition of creativity for the creator to define whether the expression is indeed novel, going as far to say that anyone other than the creator cannot be a valid or accurate judge. This is in contrast to Csikszentmihalyi’s emphasis on the creative expression serving to transform the culture or the domain.

Csikszentmihalyi (3) “creativity does not happen inside people’s heads, but in the interaction between a person’s thoughts and sociocultural context. It is a systemic rather than individual phenomenon” (3 p.23). Csikszentmihalyi tells us “To be human means to be creative,” he defines creativity as “to bring into existence something genuinely new that is valued enough to be added to the culture” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996, p.25), and “any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain, or that transforms an existing domain into a new one” (3 p.28). The word “creative” is given to expression seen as novel in relation to the surrounding culture, domain, or community, and that is novel enough to create change within that culture, domain, or community.

It seems to me we have to accept both of these ways of thinking about creativity and work with both constructs when trying to make sense of it. In other words we have to be able to accommodate both Rogerian and Csikszentmihalyian philosophies into our sense making in the manner crudely depicted in the 5C model of creativity below (5) which builds on and extends the well known 4C model (1).

I would like to think that we can make the case that education is the key environment for harnessing both philosophical positions and for learning about and preparing for creativity in a disciplinary and work domains in a complex social/cultural world. I like Carly Lassig’s Grounded Theory of Adolescent Creativity which comprises the core category, “Perceiving and Pursuing Novelty: Not the Norm. This core category explains how creativity involved adolescents perceiving stimuli and experiences differently, approaching tasks or life unconventionally, and pursuing novel ideas to create outcomes that are not the norm when compared with outcomes achieved by their peers.” (6) Carly identified three ways in which adolescents experienced creativity - creative self-expression and creativity in the service of tasks and boundary pushing. These constructs provide further evidence that these two philosophical positions are in play in the domain of educational practice.

I t

Here is someone who is very successful at integrating these two perspectives in his own practice.

Kristen Bettencourt (4) neatly captures the philosophies of these thinkers and these notes are taken from her excellent article.

Rogers (2) defines the creative process as “the emergence in action of a novel relational product, growing out of the uniqueness of the individual on the one hand, and the materials, events, people, or circumstances on the other” (p. 251). Rogers points out, “the very essence of the creative is its novelty, and hence we have no standard by which to judge it” (p.252). Rogers leaves room in the definition of creativity for the creator to define whether the expression is indeed novel, going as far to say that anyone other than the creator cannot be a valid or accurate judge. This is in contrast to Csikszentmihalyi’s emphasis on the creative expression serving to transform the culture or the domain.

Csikszentmihalyi (3) “creativity does not happen inside people’s heads, but in the interaction between a person’s thoughts and sociocultural context. It is a systemic rather than individual phenomenon” (3 p.23). Csikszentmihalyi tells us “To be human means to be creative,” he defines creativity as “to bring into existence something genuinely new that is valued enough to be added to the culture” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996, p.25), and “any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain, or that transforms an existing domain into a new one” (3 p.28). The word “creative” is given to expression seen as novel in relation to the surrounding culture, domain, or community, and that is novel enough to create change within that culture, domain, or community.

It seems to me we have to accept both of these ways of thinking about creativity and work with both constructs when trying to make sense of it. In other words we have to be able to accommodate both Rogerian and Csikszentmihalyian philosophies into our sense making in the manner crudely depicted in the 5C model of creativity below (5) which builds on and extends the well known 4C model (1).

I would like to think that we can make the case that education is the key environment for harnessing both philosophical positions and for learning about and preparing for creativity in a disciplinary and work domains in a complex social/cultural world. I like Carly Lassig’s Grounded Theory of Adolescent Creativity which comprises the core category, “Perceiving and Pursuing Novelty: Not the Norm. This core category explains how creativity involved adolescents perceiving stimuli and experiences differently, approaching tasks or life unconventionally, and pursuing novel ideas to create outcomes that are not the norm when compared with outcomes achieved by their peers.” (6) Carly identified three ways in which adolescents experienced creativity - creative self-expression and creativity in the service of tasks and boundary pushing. These constructs provide further evidence that these two philosophical positions are in play in the domain of educational practice.

I t

Here is someone who is very successful at integrating these two perspectives in his own practice.

SOURCES

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688

- Rogers, C. (1954). Toward a Theory of Creativity. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 11, 249-260

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Collins

- Bettencourt, K (2014) Rogers and Csikszentmihalyi on Creativity The Person Centered Journal, Vol. 21, No. 1-2, 2014 https://www.adpca.org/system/files/documents/journal/Bettencourt,%20Kristen%20(2014)%20-%20Rogers%20and%20Csikszentmihalyi%20on%20Creativity.pdf

- Jackson N J & Lassig C (2020) Exploring and Extending the 4C Model of Creativity: Recognising the value of an ed-c contextual-cultural domain Creative Academic Magazine #15 p 47-63 Available at: https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

- Lassig, C. J. (2012) Perceiving and pursuing novelty : a grounded theory of adolescent creativity. PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50661/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed