Over the past week we have been having an interesting discussion on creativity and value in the #creativeHE forum https://www.facebook.com/groups/creativeHE Who values creativity has been dominant theme. What has emerged is a general agreement that creators themselves are first and foremost their own judges of value and are presumably motivated to engage in creative thinking and practices by the possibility and potential of creating something of value to themselves or others. But we live in a social-cultural economic world and other people have views on whether a practice, performance or product has value and it’s their views that count as to whether something has value in a social-cultural or commercial sense. In the latter part of the discussion we saw that value was multidimensional and it is therefore not surprising that we value ‘things’ differently according to the weight we accord the different dimensions. For me, the really interesting aspect of this is how we learn to value what we value through a lifetime of exposure to the norms of our family, friends and peers, our interests and work and our culture and other cultures, noting that it is only by pursuing things which lie outside the norms that we can creatively achieve. I find this a fascinating part of the conundrum that is creativity and perhaps what we value and our judgement of it in what we do, is an part of our unique creativity.

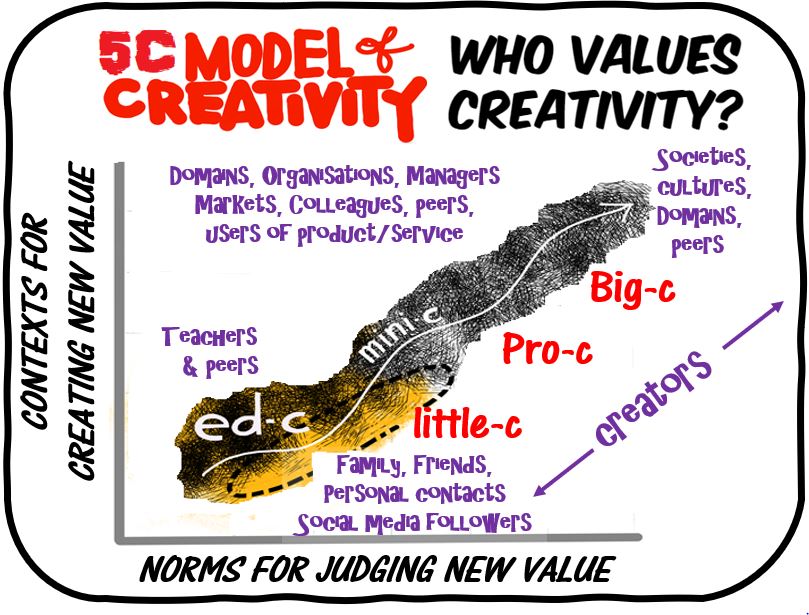

As Carly Lassig mentioned in her post we can use the 5C framework (1) we developed from the 4C framework (2) to map the contexts for creating new value and the location of norms for judging the value of creative achievements. By this I mean a tangible expression or manifestation of someone’s creativity (thinking and actions) in the formation of something new (practice, performance or product). To keep it simple the following narrative focuses only on individuals rather than collaborations or group enterprises.

In all domains of the 5C framework creators are engaged in thinking and practices that have the potential to create novelty and new value. As Carl Rogers’ humanistic perspective on creativity tells us (3), first and foremost it is the creators themselves who value their creative achievement. Only they can understand why and how the phenomenon emerged in the circumstances of their life and only they can experience the formation of a creative achievement. The value they ascribe to an achievement might be very different to the value that others ascribe.

As Carly Lassig mentioned in her post we can use the 5C framework (1) we developed from the 4C framework (2) to map the contexts for creating new value and the location of norms for judging the value of creative achievements. By this I mean a tangible expression or manifestation of someone’s creativity (thinking and actions) in the formation of something new (practice, performance or product). To keep it simple the following narrative focuses only on individuals rather than collaborations or group enterprises.

In all domains of the 5C framework creators are engaged in thinking and practices that have the potential to create novelty and new value. As Carl Rogers’ humanistic perspective on creativity tells us (3), first and foremost it is the creators themselves who value their creative achievement. Only they can understand why and how the phenomenon emerged in the circumstances of their life and only they can experience the formation of a creative achievement. The value they ascribe to an achievement might be very different to the value that others ascribe.

In the little-c domain individuals pursue novelty and create new value in the circumstances of their everyday life. Their creative achievements might only be known and valued by themselves or by the people who their achievements directly affect – for example a mum preparing a novel meal (not the norm) for her family. But such achievements might be broadcast more widely and appreciated by others – people who use Instagram, Twitter or Facebook for example have friends/followers who might be interested in their creative achievement. In such an environment some of these little-c achievements have the potential to ‘go viral’ to become part of popular culture, even if its only for a short period of time. It can be argued that the advent of social media enables more people to be exposed to individuals’ little-c creative achievements, and therefore implicated in their valuation, than at any time in our history.

In the educational domain (ed-c) judgements on the value of an individual’s achievement are usually made by a teacher against a set of pre-determined criteria but may also include external examiners if performance is in the context of an examination. As Carly indicates in her post based on her own research (4) – how a learner values their creative achievement may be different to what a teacher values. Teachers have an important role to play in sharing their judgements of value through verbal or written feedback during the production of an achievement – whether a performance or artefact. Much of this feedback is informal and spontaneous as a teacher interacts with her students, but some of the feedback might be more formal and deliberative as a teacher formally evaluates and judges a piece of work and provides written feedback. Chrissi’s post on her interactions with her tutor on a creative writing course, show values can be shared, communicated and progressively understood through this interactive relationship. Peers also may be exposed to an individual’s achievement and their teacher’s comments and they also form opinions on value. In fact, this context for being exposed to the achievements of others is the way in which we come to understand the norms of our environment and it prepares us for learning what this means in the domains in which we will work.

As we move into domains of expertise, more people are involved in decisions as to whether a creative achievement is of value. Every context is different, if we imagine the development of a new innovative product it might include peers in a design team, managers, sales reps, managers of retail outlets and the buyers and users of the product – the customers. In an entrepreneurial environment like a start-up the valuation of a new product or service it might also involve investors. In the commercial world factors other than creativity come into play in the valuation of a novel product. In the academic world where the development of new knowledge and ideas is the product of creative achievement – it is experts in the discipline who act as peer reviewers, journal editors or who sit in the committees of grant awarding bodies who judge value. If we imagine someone in the performing arts field it might include other performers, a performance director and production teams, audiences and professional critics. Of course, amongst this diverse group of actors some voices will be more influential than others in determining value and persuading others with their opinions.

The Big-C level is an extraordinary achievement in any field in which the value of what is created is widely acknowledged. The valuing of such achievements is usually led by experts in the field and promoted through awards, media and education. One of the features of Big-C creative achievements is their enduring character. They are often the foundational building blocks for culture in a domain and so are valued in a historical sense for advancing some aspect of the domain.

Perhaps one of the most interesting perspectives to emerge from the discussion related to where access to new ideas or products are restricted for commercial, political or other reasons, so that value can only be appreciated by those with the power to control the flow of information.

Thanks to all who contributed to the discussion.

Sources

1 Jackson, N.J. and Lassig, C. (2020) Exploring and Extending the 4C Model of Creativity: Recognising the value of an ed-c contextual domain. Creative Academic Magazine CAM15 https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

2 Kaufman, J and Behgetto R (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity Review of General Psychology Vol. 13, No. 1, 1–12

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/.../228345133_Beyond_Big_and...

3 Rogers, C. (1954). Toward a Theory of Creativity. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 11, 249-260.

4 Lassig, C. J. (2012) Perceiving and pursuing novelty : a grounded theory of adolescent creativity. PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50661/

In the educational domain (ed-c) judgements on the value of an individual’s achievement are usually made by a teacher against a set of pre-determined criteria but may also include external examiners if performance is in the context of an examination. As Carly indicates in her post based on her own research (4) – how a learner values their creative achievement may be different to what a teacher values. Teachers have an important role to play in sharing their judgements of value through verbal or written feedback during the production of an achievement – whether a performance or artefact. Much of this feedback is informal and spontaneous as a teacher interacts with her students, but some of the feedback might be more formal and deliberative as a teacher formally evaluates and judges a piece of work and provides written feedback. Chrissi’s post on her interactions with her tutor on a creative writing course, show values can be shared, communicated and progressively understood through this interactive relationship. Peers also may be exposed to an individual’s achievement and their teacher’s comments and they also form opinions on value. In fact, this context for being exposed to the achievements of others is the way in which we come to understand the norms of our environment and it prepares us for learning what this means in the domains in which we will work.

As we move into domains of expertise, more people are involved in decisions as to whether a creative achievement is of value. Every context is different, if we imagine the development of a new innovative product it might include peers in a design team, managers, sales reps, managers of retail outlets and the buyers and users of the product – the customers. In an entrepreneurial environment like a start-up the valuation of a new product or service it might also involve investors. In the commercial world factors other than creativity come into play in the valuation of a novel product. In the academic world where the development of new knowledge and ideas is the product of creative achievement – it is experts in the discipline who act as peer reviewers, journal editors or who sit in the committees of grant awarding bodies who judge value. If we imagine someone in the performing arts field it might include other performers, a performance director and production teams, audiences and professional critics. Of course, amongst this diverse group of actors some voices will be more influential than others in determining value and persuading others with their opinions.

The Big-C level is an extraordinary achievement in any field in which the value of what is created is widely acknowledged. The valuing of such achievements is usually led by experts in the field and promoted through awards, media and education. One of the features of Big-C creative achievements is their enduring character. They are often the foundational building blocks for culture in a domain and so are valued in a historical sense for advancing some aspect of the domain.

Perhaps one of the most interesting perspectives to emerge from the discussion related to where access to new ideas or products are restricted for commercial, political or other reasons, so that value can only be appreciated by those with the power to control the flow of information.

Thanks to all who contributed to the discussion.

Sources

1 Jackson, N.J. and Lassig, C. (2020) Exploring and Extending the 4C Model of Creativity: Recognising the value of an ed-c contextual domain. Creative Academic Magazine CAM15 https://www.creativeacademic.uk/magazine.html

2 Kaufman, J and Behgetto R (2009) Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity Review of General Psychology Vol. 13, No. 1, 1–12

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/.../228345133_Beyond_Big_and...

3 Rogers, C. (1954). Toward a Theory of Creativity. ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 11, 249-260.

4 Lassig, C. J. (2012) Perceiving and pursuing novelty : a grounded theory of adolescent creativity. PhD thesis, Queensland University of Technology. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50661/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed